|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(The 21 Demands were, in short, an ultimatum issued by Japan to China,

divided into 5 groups which each gave Japan seperate rights and/or territory

in China. China would have become a Japanese protectorate.)

China’s weak performance in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) made China

look like a big buffet to some of the world’s powerhouses. Russia,

France, Britain, Germany, and Japan were all ready to carve up China.

And that’s exactly what they did. Germany leased the Shangdong Peninsula,

Russia leased trusty Port Arthur in southern Liaodong, Britain got Weihaiwei

and areas around Hong Kong, and France leased some land around Guangzhou

Bay. Poor China was really defenseless to stop the preceedings, and

these countries took more than their share of liberties with just about

everything in China, including land, rights, and any other interests they

seemed fit to toy with. China would end up turning to the merchant

class in an attempt to find an ally in this troubled time. This grasp

for help came in what was known as the Rights Recovery Movement.

So now China, being battered and bruised, was at the end of the

line. Late attempts to save the dynasty, like anti-opium drives and

educational reforms were valiant, but proved to be no match for the downward

spiral of the empire. The new horizon became evident in 1908 when

Empress Cixi and Emperor Guangxu died “coincidentally” within one day of

one another, and Yuan Shikai was dismissed from his governmental duties.

Three years later, China got itself into problems by trying to nationalize

the major railway system. They could accomplish this only by taking

ridiculously complicated loans from foreign countries. The plans

of the government and the loans caused more than a small stir, and revolt

reared it’s ugly head in the form of revolutionaries. But trying

to avoid Civil War, China made a compromise with these rowdy men wrestling

for reform. So the child who was officially the emperor was abdicated,

and Yuan Shikai was called upon to become leader of this new republic.

Yuan still had the support of his army, had a reputation as a reformer,

and had a decent amount of foreign support. It was now Yuan’s move.

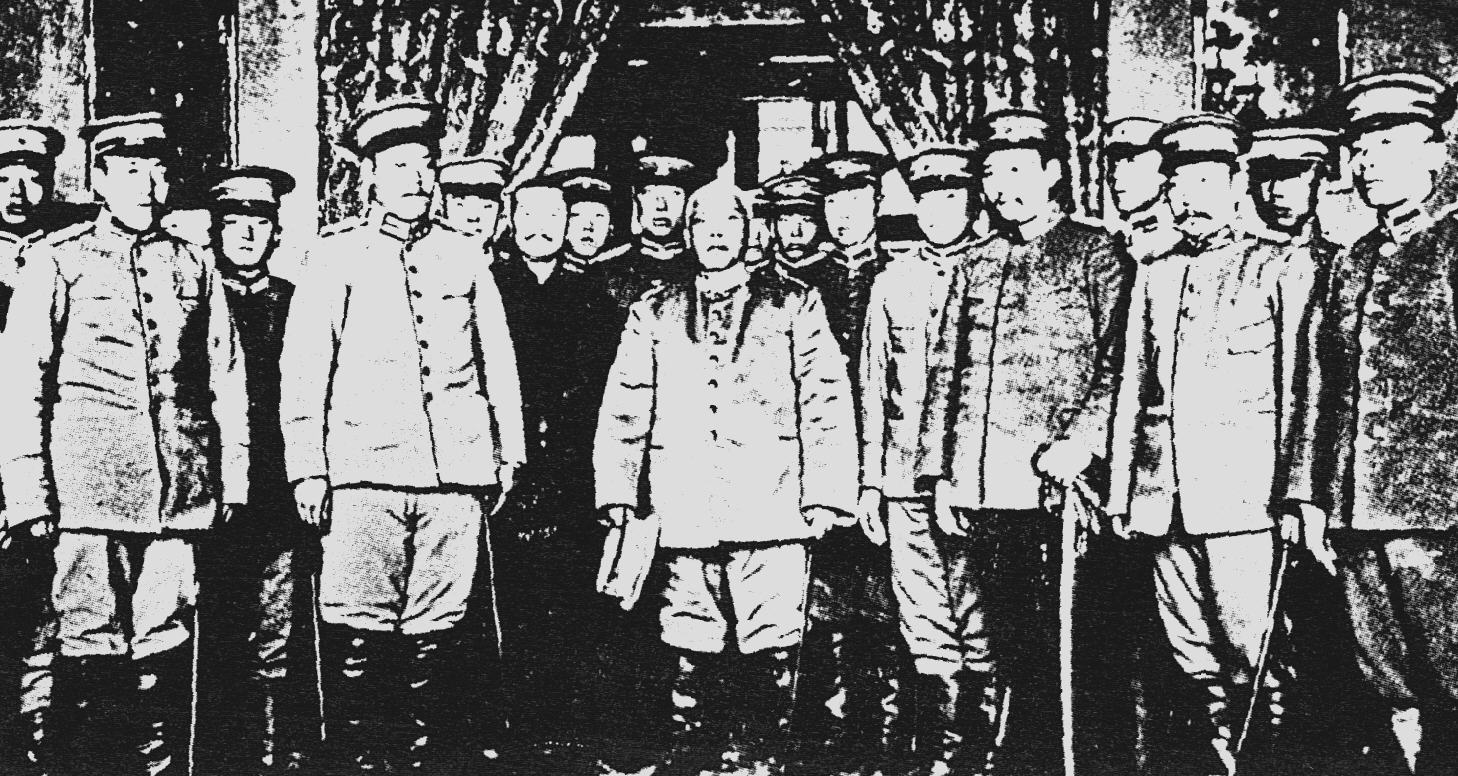

Yuan Shikai (center) standing amongst members

of his military

The system was still new. Yuan may have

been a smart man, but he definitely did not have the strongest system backing

him up. So the public, still somewhat in a form of shell shock, watched

as Yuan took over as a dictator. He made sure that no one opposed

him by allowing only a small percentage of the Chinese population vote.

When another party, the Nationalist Party showed signs of promise behind

the leadership of Song Jiaoren, Yuan quickly had Song killed and continued

on with his dreams of centralization. He was not without problems

though.

While maintaining his big cheese persona

in the public eye, things were often disastrous behind the scenes.

There was still a lack of money coming into China, and Yuan needed money

for reformation programs. The only way to get this money was to revert

back to the foreign loans. This of course got under the skin of the

nationalists, because these loans had so many backdoors and so much baggage

that it was not exactly in the taste of the nationalist fervor. Meanwhile,

Japan was playing the part of the watcher, getting ready for the right

time to take action. That “right time” came on May 7th, 1915, and

it was an ultimatum which was from there on out to be known as the 21 Demands.

The 21 Demands were sent to China and urged

upon the Chinese government. The Japanese government still stressed

however that this was less of an ultimatum and more of a negotiated request.

The subject is still under much debate, but the Chinese government insists

that the entire thing was no more a request than were any of the demands

made on China by foreign powers in this time. The literal declaration

was given from the Japanese minister at Peking to the Chinese Minister

of Foreign Affairs, and it was delivered with somewhat of a threat.

The Japanese government said that if they did not receive what they thought

was a satisfactory response by 6 p.m. on May 9th, 1915, then they would

take whatever action they would deem necessary to rectify the situation.

One can wonder what exactly the Japanese

might have done in terms of taking “necessary action”, but of course we

will never know, because the Chinese replied to the ultimatum on May 8th,

1915. It took Yuan just over one day to make his decision, and what

came out of it was clearly only so because of the fact that other countries

were so preoccupied elsewhere because of the World War which was going

on. However, while China was hurt by this, it was not the woodshed

beating that Japan had hoped for, as the fifth group of demands was avoided.

Still, much was lost. China was to accept most of the demands, and

still woefully stated that although they had no choice but to give in to

some of the ultimatum, that they would refuse to associate themselves with

any revisions that would involve agreements between a group of other powers

over the “territorial independence and integrity of China.”

The 21 Demands were divided into five distinct

groups. Each group had a number of articles in it, and some of those

articles had sub-articles. The most important point of the first

group was recognition of Japanese rights in Shangdong. This was addressed

in the first article of group 1. This article expressed that no other part

of Shangdong would be able to be leased under any other Power under ANY

circumstances. Article 3 stated that Japan would be able to building

a railway in China connecting Chefoo with the then current Kiaochou Tsinanfu

Railway. The final article of the group, article 4, stated that China should

open up certain cities and provinces in Shangdong to the residence and

commerce of foreigners. Those places were to be specified later.

This opening demand was a strict start, and showed how Japan was not going

to disregard territories in which other countries had some stake.

Group 2 moved away from the Shangdong province

and focused a bit more on Japanese rights up north in the territories of

Mongolia and Manchuria. Now, Japan had already been leasing part

of Port Arthur, the South Manchurian Railway, and the Antung-Mukden Railway.

Article 1 of the second group extended the terms of these leases for another

ninety-nine years. Article 2 said that Japanese industrialists were

to be allowed into South Manchuria and East Inner Mongolia for business

and industrial needs, or even to farm the land. Articles 3 and 4

followed right up on that by saying that any Japanese subjects had the

right to enter those provinces for any reason, including for the purpose

of setting up a permanent residency, and also for mining purposes.

Obviously Japan was being frank and bold in their demands. Article 5 entered

new territory in terms of the demands, and it was requiring China to get

permission from Japan in advance if it wanted to raise funds to build a

new railway, or if it were to try to obtain a loan under the security of

South Manchuria or East Inner Mongolia. Here Japan was putting itself

in an authority position in relation to China. Article 6 pressed

on, saying that if China wanted to obtain the service of political, financial,

or military advisors out of South Manchuria or East Inner Mongolia, then

the Japanese government would have to be first consult. These particular

articles were a slap in the face to China and a clear attempt by Japan

to get China firmly into it’s control. The final article put a stamp

on the group, saying that control of the popular Kirin-Chngchun Railway

be handed over to Japan for ninety-nine years. Japan was not done

though. They wanted a clear foreign domination in Japan, and were

determined to get it through these historically monumental articles.

In group 3, the Japanese were going to

move in on the Han-Yeh-Ping Iron and Steel Company. Article 1 of

the group said that the Han-Yeh Ping Company would soon become jointly

owned by China and Japan. The company was the largest Iron and Steel

company in all of China, and Japan knew this well. It also said that during

the short time until it was jointly owned, China could not dispose of it

or let anyone else become involved in the company. Here the Japanese

show their distrust in China even in it’s weakened state. Neither

country was going to play around about any fake acceptance for one another.

Japan also covered the other end in the second article of the group, saying

that any mines that might be of interest to the company were not to be

worked by anyone other than the Han-Yeh-Ping Company, and that any moves

of any real interests could come about only from consent.

Onwards to group 4. By this time

Yuan Shikai must have been irate. Almost jokingly, each of these

articles begins with something along the lines of “The Japanese and Chinese

Government, with the object of effectively preserving the territorial integrity

of China, agree to the following article:”. Group 4 stated that China

should not cede or lease any harbour, bay, or coastal territory, to anybody

other than Japan. China’s ability to uphold each of these

demands (this one in particular question) was not an issue at this early

stage, but it was clear that it could one day be one.

Group 5 is where things clearly got out

of hand in terms of China even being able to oblige. Whether it was

Japan overstepping it’s bounds, or China putting up a stop sign is a matter

of question. However, group 5 is clearly one of the more interesting, and

would have been twice as much so had it been put into effect. There

was a good deal to this group. One part would have made it so Chinese

would have to employ Japanese military, political, and financial advisors.

This in itself was ludicrous. Another part was to allow Japanese

hospitals, temples, and schools in China to own land. Yet another

part wanted to put Japanese police into high jobs in China in order to

“improve” the Chinese political system which, in the eyes of the Japanese,

was faulty and not skewed enough towards those of Japanese decent.

The would be group did not end here though.

It further stated that China was to buy

a stated amount of arms from Japan, which at this point appeared to be

a point of Japan almost giving permission to parts of China that they had

holds on to buy arms from those who would tell them how to use the arms.

The group further wanted points giving Japan more railway building rights,

strong building control in Furmosa and Fukien, and the right of Japanese

subjects to preach in China. From Japan’s perspective, group 5 would

have made it so that they had all their grounds covered, including those

of somewhat minimal importance.

The historical significance of the 21 demands cannot be underestimated,

not only because it was a prime example of that Japan’s dominance of China

in that period but also because of it’s chronological placement in East

Asian history. The event falls just four years after the fall of

the empire in China and during the first World War. It’s a great

example of the ever stacking burden that China had being piled onto it

at that time. The problem is that the stack can only get so high,

and there can only be so much burden, before the stack falls, the burden

collapses everything around it, and the country explodes. What comes

out of it, is something monumental.

Bland, J.O.P. China, Japan, and Korea. London: William Heinemann,

1921.

Ch'en, Jerome. Yuan Shih-k'ai. 2nd. ed. Stanford: Stanford University

Press, 1972.

Coox, Alvin D. China and Japan: A Search for Balance Since WWI.

Santa Barbara and Oxford: ABC-Clio, Inc. 1978.

Kordelj, Edvard. Socialism and War. London: Methuen and Co.

Ltd., 1960.

Mackman, Stephen R. Power and Politics in Late Imperial China.

Berkely and Los Angeles: University of California Press, Ltd., 1980.

Tappan, March. The World's Story- Volume 1. Boston and NY: Houghton/Mifflin

Co./ The Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1925.

Young, Ernest P. The Presidency of Yuan Shih-k'ai. Ann Arbor:

The University of Michigan Press, 1977.

http://www.fba.nus.edu.sg/student/bk3400/t2_9899_student/chi_p&s_ae3/History.html- (History of China from 1911 through 1949 with additional material on warlords)

http://library.thinkquest.org/26469/history/1928.html - ( ThinkQuest's detailed site with all you could ever hope to know about China)

http://www.history.unimelb.edu.au/coursematerials/China/M2M_06_May4.html(Brief Chronology)

http://www-chaos.umd.edu/history/republican.html- (Overview from Sun-Yat Sen through 1928)

http://www.fcc.sophia.ac.jp/Faculty/Devine/documents/stone.html- (Detailed layout of the Demands)

http://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/- (Current flags of the world)

http://www.unc.edu/courses/hist083/yuan_shikai.htm-

(Yuan Shikai photos)