|

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

|

Abstract

During the 14th and 15th centuries, several horrific events took their

toll European lifestyles. Famine, disease and war brought death and

devastation in many forms. Many God-fearing people believed the end

of the world had arrived, as - according to the Christian Bible - these

events signaled the arrival of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, mythical

figures whose destruction of the Earth preceded the second coming of Christ

and the advent of Judgement Day. The Great Famine of 1315-1317 entered

first with a change in climate and subsequently exhausting effects on crop

yields. It was soon followed by the Black Death, a potent attack

of bubonic plague that would be remembered as one of the deadliest outbreaks

in history. The Black Death coincided with the beginning of the Hundred

Years War, which would dramatically change relations between England and

France, the two most powerful countries in Medieval Europe.

Historical

Background

For two hundred

years, the world had been experiencing a warm era, reaping the benefits

of a long growing season. Grain was grown in abundance, and food

was plentiful. By the 14th century, however, the weather had begun

to cool slightly. It seemed not to make too much difference aside

from pushing spring thaw back a little and bringing harvest time earlier.

1315 signified a turn for the worse, and one year of bad weather sent Europe

spiraling into one of the worst famines in European history.

Medical practices

had yet to advance in years leading up to this time, and many illnesses

were still treated with home remedies and superstitious “cures.”

Therefore, Europe was completely unprepared for the virulent bout of Black

Death that would strike in the 1340s and 1350s. Traditional treatments

proved for the most part ineffective, and fear of the disease sent people

scattering across the continent, unwittingly carrying the plague with them.

With no effective protection from the disease, some clung to their superstitious

potions and incantations, some prayed in hopes theif faith would save them,

but many merely waited in fear of the day the plague would reach their

town.

Constant unsuccessful

attempts to mend the rift between England and France had led to an even

more awkward situation; by the time of Henry II, the king of England had

claims to more French land than the king of France. When his great-great-grandson

Edward II married Isabella, daughter to Philip IV, king of France, the

two countries met with an even stranger predicament; the only male heir

to the throne of France after Philip’s death was Edward III, king of England.

France’s efforts to keep him from claiming the throne angered Edward and

formed the impetus to start a war that would last for the next 117 years.

Research

Report

In the sixth chapter

of Revelation, the last book of the Bible, John describes the horrors invited

into the world upon the opening of the Book of Life. This Book has

seven seals, and as each is opened, new and terrible things are introduced

to Earth. The first four of these seals unleash the four Horsemen,

instruments of Death, War, Plague, and Famine. While the abhorrences

that follow are equally frightening, the four Horsemen stand out in history

as warning signs of the end of the world, and in the 14th century, they

paid a visit to Europe and the surrounding world.

Background

of the Four Horsemen

The first Horseman

rides a white horse, and he represents the anti-Christ, proclaiming false

prophecies and crying the end if the world. He wears a golden crown

and carries a bow in his hand. He is crafty, spreading a false sense

of God’s Will while hiding behind the facade of Divine favor.

The second Horseman

comes colored in the blood of conflict. To roughly translate what

Emil Bock writes, the Red Horseman rides “to destroy peace on Earth and

to sow fighting amongst the people.” With his arrival, countries’

leaders will fight each other, while the Horseman oppresses the faithful

of God’s children.

The Black Horsemen

brings with him disease and famine. His actions are directed to affect

mostly the economy of a society, driving up food prices when crops fail,

and making labor more valuable when plague kills off workers. Under

him, the wealthy thrive upon the misfortune of the poor, who are unable

to pay for the items they need to survive.

Finally comes

Death, riding a pale horse - one which is often described as ashen or greenish-yellow,

the color of a corpse. Death brings with him Satan’s minions, and

they in turn wreak havoc on mankind’s souls, throwing millions into the

“Great Pit,” which descends directly to Hell. His goal is to destroy

all that has life on Earth.

SIGNS OF

THE APOCALYPSE IN 14TH CENTURY EUROPE

The Great

Famine of 1315-1317

In truth, the

Great Famine lasted seven years, from 1315 to 1322, for which reason it

is sometimes compared to the famine of Egypt in Genesis 41. The first

three years, however, were the most severe, and they adversely affected

the next decade. Even chroniclers in the 18th and 19th centuries

pointed out the severe food shortages and torrential weather patterns of

1310-1320.

One major cause

of the famine was sudden changes in the weather. The Little Ice Age,

the first major ice age for 10,000 years, was in its beginning stages,

putting an end to the Medieval Warm Period that had prevailed for the previous

two centuries. This cold trend began in different places at different

times, but between 1250 and 1400, the entire planet surrendered to colder

climates. Extremely cold portions of the Little Ice Age have been

attributed to a lack of sunspots, extremely hot spots on the sun’s surface,

and the volcano Tambora’s (Indonesia) 1815 eruption, which preceded the

“Year Without a Summer” in New England and Northern Europe. Glaciers

advanced from the north and from the mountains, and average temperatures

dropped as much as nine degrees, actually making the climate similar to

today’s, but nevertheless colder than Europe and Asia had seen in millennia.

Northern seas froze, and China’s ancient orange groves died off in the

harsh winters. Despite colder winters, summers were about the same

in temperature, but they were wetter and came later. Eventually,

Europe learned to cope with the new climate, with London having Frost Fairs

when the Thames River froze, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was the product

of a summer vacation ruined by the inclement weather of the Little Ice

Age. Long before these events, though, northern Europe struggled

with two major climatological phenomena: abnormally cold winters between

1310 and 1330 and very rainy summers from 1310 to 1320, the worst being

1315 and 1316.

Many people at

the time saw the famine as a result of supernatural occurrences.

A comet was visible from 1315 to 1316, and it is recorded in Chinese as

well as European chronicles. Comets were traditionally bringers of

famine and strife. Swedes and Britons witnessed red lights reminiscent

of spilled blood in the night sky, and they were seen as signs of pestilence

or war. Another ominous celestial event, Europe saw a lunar eclipse

in October of 1316, and France was rocked by earthquakes in 1316 and 1317.

In hindsight, all of these events were seen as forewarners of the Great

Famine.

The rains began

early in May of 1315, and they did not let up until September. Consequently,

grain could not ripen in the dry, sunny weather it needed, and bread was

difficult to come by. Poor soil and farming practices contributed

to low yields long before this time, but the unrelenting weather assured

the harvest of 1315 would be far more devastating. The rains continued

to return, altering spring and fall harvests until 1321. Manors in

England reported wheat yields from 1315 to 1317 as much as 20 percent below

normal for the period, and 30 percent or more below average yields of the

previous decade. From the late 12th century to the late 14th century,

grain prices were at their highest during this decade.

Grains were not

the only crops affected, however. Friedrich Dochnal of the wine town

of Neustadt, Germany, reported sparse production of wine in 1316 and 1317.

Sporadic good wine years (in quantity) ensued, but in Dochnal’s opinion,

no good quality wine was seen in Neustadt until 1328.

The cold weather

also took its toll on the livestock. Westminster manor in England

reported sheep fleece to weigh 1.35 pounds on average in the 13th century.

Cold weather encourages thicker, heavier animal coats, and in 1317, the

average fleece weighed 1.93 pounds. These thicker coats also made

it difficult for sheep to reproduce, and lambs were few, making it important

to get as much fleece as possible from existing sheep.

The shortage

of food brought many families and villages to drastic measures. Animals

were eaten despite the need for them in the field. Children were

abandoned because families could not feed them; the fairy tale “Hansel

and Gretel” is an example of such events, and it probably had its roots

in true stories of famine. Elderly people starved to feed their younger,

stronger relatives, and some people even resorted to cannibalism.

Weakened by hunger, many people died of illness, and nobles and clergy

were no better off than peasants. In Bingen, a small town on the

Rhein River, a white tower stands about 100 meters offshore. Legend

has it that this tower was built by a greedy bishop who was keeping food

from the people of the village. He built himself a tower with no

doors so that no one could steal his food, and he sealed himself inside,

only to be attacked by starving rats from the village who swam out to the

tower after the food.

Although the

worst years of the Great Famine were over, Europe still struggled to bounce

back for the next ten to fifteen years. Grain prices eventually returned

to normal, and farming adapted to the shorter growing season. Population

would soon begin to grow again, but not until the end of the Horsemen’s

reign of terror was over.

Black Death

(1347-1350)

The Black Death

originated in Asia, although where is unsure. It ravaged India and

the Middle East, leaving a trail of death along the Great Silk Route before

reaching the Crimea - present-day Ukraine - where it would eventually be

loaded on Genoese ships bound for Italy. Kaffa’s citizens were worried,

but they were sure God would protect the Western world from a disease that

“punished” pagans in the exotic East. The Mongols believed the disease

came from Italy, and in retaliation they stormed the city of Kaffa in 1347.

Locked out by the city’s walls, they catapulted corpses of plague victims

into the city, where the corpses infected the water supply. The Genoese

merchants that escaped carried the disease to Constantinople and on to

Messina, Sicily, starting an era of death unimaginable.

Most of the ships’

crews were dead by the time they reached Messina’s harbor, but somehow

the disease still reached the shores. As with the Great Famine, people

looked to supernatural causes for the Pestilence, as they called it.

They said the planets were aligned wrong, or earthquakes had disturbed

some higher balance. In truth, rats on the ships carried the disease

ashore via the fleas that carried in their blood the bacteria that causes

Black Death - Yersina pestis, identified independently by Alexandre Yersin

and Kitasato Shibasabaroo in 1894. The Oriental Rat Flea is the most

common carrier of the disease, but over 100 species of fleas have been

known to transmit the bacterium. The disease is normally isolated

in the rat community, but a change in weather or food supply probably drove

rats to seek out habitats already occupied by humans, thus increasing the

risk of transmission through a flea bite. The bacteria clot the blood

in a flea’s stomach, making it difficult for fleas to feed on blood.

When they try to suck an animal’s blood - rats or humans - the blood in

their stomachs forces them to regurgitate, carrying infected blood back

into the host’s bloodstream.

The disease comes in three forms

- bubonic, the most common, infecting the lymph system; pneumonic, which

spreads to the respiratory system; and septicaemic, in which the bacteria

moves directly into the bloodstream. Bubonic carried a 60 percent

mortality rate, while the other two forms were almost 100 percent fatal,

and all were extremely painful. Survivors were then immune to future

attacks by the bacterium. People refused to care for the sick, not

only because they feared infection, but also because of the horrific stench

that emanated from every bodily fluid, and they would wear bags of herbs

and flowers to “ward off” the disease, giving root to the child’s rhyme

“Ring Around the Rosie”. The ring symbolized the danse macarbe that

passed the disease to all factions of life, and “rosie” described the complexion

of an infected person. Posies were carried in the bags of the healthy;

“ashes” is a mimic of the sound of sneezing, and falling down symbolizes

death. Perhaps the most interesting fact about bubonic plague that

affects people today is that some medieval survivors developed an immunity

that they passed on through a genetic mutation. This mutation may

be linked to an immunity to HIV, since the virus attacks the body much

as Y. pestis does.

Ships refused

at Messina traveled on to other European ports, such as Florence.

A century before the Renaissance, this trade center became so overwhelmed

with the Black Death that they had to dig huge trenches to bury the dead,

who were brought out by the cartload, rather than entomb them in cemeteries.

Giovanni Boccaccio describes in the introduction to his Decameron priests

walking to the Florence cemeteries followed by three and four funeral biers

stacked with corpses. He also relates a case where pigs died in the

street simply from rolling in the rags of a poor man who died of the plague.

Many fled to the countryside to escape this pathological rampage, but the

disease inevitably caught up with them. Their care-free parties and

revelry would be cut short by mortality, as Poe describes in “The Mask

of the Red Death.” The poet Francesco Petrarch fled to Parma, where

the disease eventually claimed the woman he loved.

In Germany, the

plague initiated dangerous behaviors. The Brotherhood of the Flagellants

stemmed from Eastern European practices; it was a group of men who believed

in scourging themselves in God’s name so they would be saved from Hell.

They mercilessly beat themselves in front of the townsfolk, sometimes so

hard their blood landed in the crowd. Many Germans also blamed Jews

for causing the plague by poisoning local wells. They were tortured

and burned at the stake; as many as 8000 Jews were “put to the question”

like this in the city of Strasbourg alone. Despite Germany’s religious

convictions, even the Church was unsure of how to proceed. Pope Clement

VI sat between two fireplaces to prevent illness at his refuge in Valence,

helpless to do anything but pray for the lives of his subjects.

Abandoned projects

such as cathedrals stood half-formed, with their artisans dead at their

bases, and ships whose crews had been completely eliminated en route to

their destinations floated aimlessly on the seas as England waited fearfully

for the day the Black Death would cross the Channel. The disease

might not have survived past its first year if not for an unusually warm

winter, now believed to have been caused by El Nino’s effects. Ships

from France and Italy brought the Great Mortality to England in several

ports, carrying it up the Thames River and into London. Nearly half

of London’s population was killed, and the lack of clergy and workers completely

disrupted the once-stable religious and economic settings.

From England, the plague moved

into Ireland, where one monk - Brother John Clynn - would spend his final

hours alone, writing of his experiences in hopes someone will survive what

seems to many to be the end of the world; he died writing his chronicle.

Like many other religious communities, Brother Clynn’s was totally wiped

out by the Pestilence. The lack of clergy meant that education could

not be limited to the Church, and universities designed to educate the

common person quickly sprung up in the aftermath of the plague.

The Hundred

Years War (1336-1453)

(This gets

confusing! Click

here

to see a family tree for the British and French royal families)

For centuries,

England and France held a bitter rivalry that rulers continuously tried

in vain to amend, often by intermarriage. Consequently, when Henry

II of England married Eleanor of Aquitaine, the territory that came with

the union gave the king of England control over more French lands than

the king of France. This juggling of lands would finally come to

a head in the early 14th century, when both countries struggled for control

of Flanders. The French-ruled territory became a target for England,

as it was an ideal area for growing the much-desired wine grapes, and its

booming cloth industry gave England a market for wool exports. The

ensuing battles between France and England sent Flanders spinning into

a civil war, with the merchants on one side and the nobility on the other.

To make matters

worse, Charles IV died in 1328, the last son of Philip IV and, like his

brothers before him, without leaving a male heir. Charles’ sister,

Isabella had a son with her husband, Edward II of England - a son who succeeded

his father to the throne the previous year. To keep the young Edward

III from ascending the French throne as well, French officials reinstituted

the ancient Salic Law, stating a female could not pass any inheritance

from her father to her son (females already could not inherit anything

themselves outside of a dowry). Instead, the Capetian rule in France

ended, and Philip’s nephew, Philip V of the Valois family, reigned as king.

Still, Edward felt the crown should have been his, and he planned to attack

France with a vengeance.

Before he could

take over France, however, Edward first had to secure his position as the

ruler of England. His mother and her lover, Roger Mortimer, had been

ruling England in his stead, and in 1330, Edward invaded Nottingham Castle,

removing them from power and ordering Mortimer’s execution and Isabella’s

institutionalization. After defeating French sympathy in Scotland,

Edward then moved on to the mainland. France assembled a blockade

in 1340 to keep British ships from trading with Flanders, but the English

navy proved too strong a force. They crushed the French ships, gaining

full control of traffic in the Channel and North Sea and assuring all fighting

henceforth would be in France. Edward began a second attack in 1345,

only to have his army ravaged by the Black Plague. The French pushed

the British back to Crecy, where England retaliated to defeat them with

the help of the long bow and the advantage of their position atop a hill.

France did not learn its lesson immediately, however, and they were defeated

in a similar situation at Poitiers in 1356. A change in fighting

tactics leveled the field, so to speak, and in 1360, the first phase of

the Hundred Years War ended in a treaty signed in 1360 at Bretigny.

Fighting soon

began again, with most of the fighting from 1376-1381 concentrated in Brittany,

English land in France. Thomas Woodstock led a march from Brittany

to Paris and back in 1380, an event that led to the Peasants’ Revolt in

England in 1381, one of many uprisings and civil wars caused by battling

between England and France at the time. Suppressed by fighting at

home and disheartened by defeats in France, England retreated in the 1380s,

and the conflict was reduced to piracy in the English Channel. Richard

II was more awed by the French court than his own, and he took great efforts

to make peace with Charles VI, then king of France. After the death

of his first wife, Richard married Charles’ daughter Isabella. He

then turned his campaigns on Ireland, where he died in 1399. His

cousin, Henry IV, continued Richard’s peaceful policies, signing a treaty

in 1406 with France and continuing to fight in Ireland and Wales.

Henry V turned

back to France, marching on Normandy in a campaign that extended from 1413-1422.

France had been weakened by internal conflict, which began in 1407 when

the Duke of Orleans killed the Duke of Burgundy. Henry swooped in

claiming ancestral inheritance from France, including the French crown

and all lands as appropriated in the 1360 treaty. He played both

sides of the feud, even going as far as to marry Charles VI’s daughter

Catherine, all the while planning his invasion. After his sudden

death, his son Henry VI carried on his campaign, ascending the French throne

soon thereafter.

Henry V’s brother

John, the Duke of Bedford, was the head of the government in France with

his seat at Rouen in the castle Joyeux Repos. He signed the Treaty

of Amiens with the Duke of Burgundy in 1423, and married the Duke’s sister.

Meanwhile, John’s brother Humphrey, the Duke of Gloucester, married Jaqueline

of Hainault, invading her territory in 1424 and causing friction with Burgundy.

England spent 1422-1428 expanding its control in France, taking all of

northern France and progressing until the siege of Orleans at the end of

1428.

In 1429, a young

peasant girl named Joan of Arc came to Charles VII to help him regain his

throne. Based on a vision from God, she accepted control of the French

army, defeating the English at Orleans and reviving French spirit.

The English were driven off the throne, and Charles took his position there

in July of the same year. Joan was captured the next year and sold

to the English, who tried and executed her for heresy and witchcraft.

Still, England continued to lose ground in France, and the Parliament refused

to continue to fund the war. After the death of Bedford’s wife, Burgundy

pledged his allegiances to Charles. The Pope called a meeting at

Arras in 1435 between England, France and Burgundy to try to find a peaceful

solution. Burgundy and France secured their alliance, and England

was forced to surrender Paris in 1436.

Burgundy made

further no moves against England, but the French continued to push the

English out of northern France. In 1438, they also began attacking

English Gascony, in the south. The Earl of Suffolk traveled to France

in 1444 to negotiate peace, arranging the marriage of Henry and Margaret

of Anjou in 1445. Fighting ceased until 1449, when British mercenaries

attacked Fougeres in Brittany. Charles VII compensated by seizing

Rouen. Thomas Kyriel made one last effort to regain England’s holds

in Normandy, but he was defeated at Formigny. France gained control

of Gascony by 1453. England now controlled no land on the French

side of the Channel except for the port of Calais.

These three events

piled upon each other pummeled Europe with devastating results. Medieval

European life was centered around the Catholic Church and its teachings.

Famine, Plague, and War all paved the way for Death to ride through, flinging

millions of God-fearing people - peasant and noble alike - into the Great

Pit. Although the world survived beyond the Middle Ages, for Medieval

Europeans, the prophecies of the Book of Revelation seemed to be coming

true right before their eyes; Judgement Day had arrived.

Historical

Significance

The predicaments

of the 14th century drastically changed the ways of thinking in Medieval

Europe. A way of life once centered around the Catholic Church and

a feudal government was shattered when faith in God could not make the

crises disappear and lords could not supply their subjects with enough

food and protection. Peasants turned to the Church and the wealthy

for prayers and support in light of the Great Famine and the Black Death,

but priests and nobles were at a loss to help them; they were just as susceptible

to hunger and disease. In some cases, entire communities of religious

ministers were wiped out by the plague, because such communities were refuges

for the travellers who carried the disease to various parts of Europe.

The war raged off and on for more than a century, and the peasants were

caught in the middle; nobles battled each other on the side, and the unrest

caused by the rivalry between England and France led to several civil wars.

These events were precursors to the Reformation and the radical changes

in government that would occur in the following centuries.

References

Apokalypse: Betrachtungen über die Offenbarung des Johannes,

Emil Bock; Ó1952, Verlag Urachhaus

The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio, translated by Mark Musa and

Peter E. Bondanella; Ó1977, W. W. Norton

and Company, Inc.

The Great Famine: Northern Europe in the Early Fourteenth Century,

William Chester Jordan; Ó1996, Princeton

University Press

The One Hundred Years' War, Robin Neillands; Ó1990,

Robin Neillands

Knights and Peasants: The One Hundred Years' War in the French Countryside,

Nicholas Wright; Ó1998 Boydell Press

Web Resources

Report:

http://home.att.net/~armageddon_watch/megiddo.html#begins

- a look into the Biblical history of the Four Horsemen

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/famin1315a.html

- a short overview of the Great Famine of 1315

http://www.ukans.edu/kansas/medieval/108/lectures/black_death.html

- a report on the Great Famine and the Black Death

http://www.vehiclechoice.org/climate/cutler.html

- a detailing of the events leading up to and surrounding the Little Ice

Age

http://www.discovery.com/stories/history/blackdeath/blackdeath.html

- interactive site with a "tour" of plague-ridden Europe and "interviews"

with the people who lived through it

http://ponderosa-pine.uoregon.edu/students/Janis/menu.html

- a in-depth look at several aspects of the Black Death

http://www.ukans.edu/kansas/medieval/108/lectures/hundred_years_war.html

- the first half of the Hundred Years War

http://www.oseda.missouri.edu/~kate/guardians/gailsden/100yrs.html

- the second half of the Hundred Years War

Pictures:

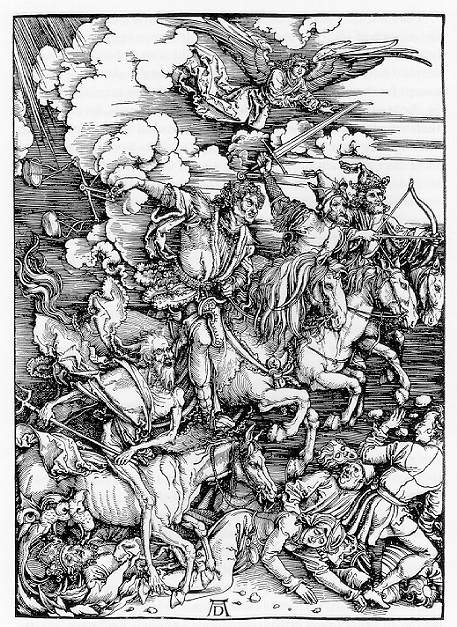

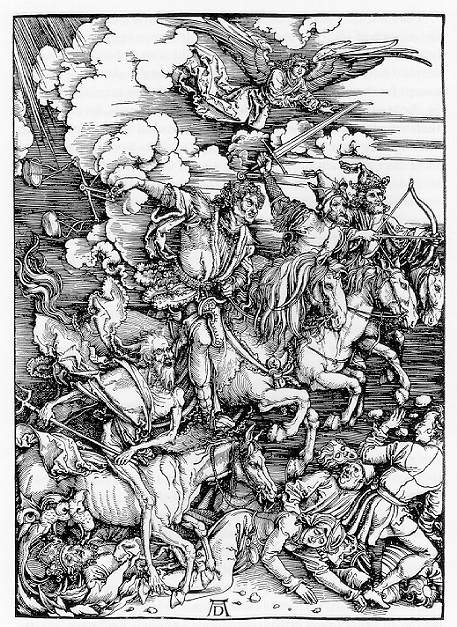

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/D/durer/4horse.jpg.html

- Albrecht Dürer's Four Horsemen etching

http://www.ac.wwu.edu/~stephan/Graunt/pictures/coffins.html

- a drawing of coffins being removed from houses during the Black Plague

http://holdon81.homestead.com/familytree.html

- the British and French monarchial family tree

Extras (for fun):

http://und.fansonly.com/trads/horse.html

- Notre Dame University's Legendary Four Horsemen

http://kadira.tripod.com/index.html

- Highlander: The Series' Connection to the Four Horsemen