abstract

Japanese ink art is prized as a beautiful symbol of Japanese culture. Though

highly influenced by China, Japanese painters succeeded in creating highly

original and distinctive styles and works. Additionally, much of this

suiboku

is strongly tied to Zen Buddhism, a religion that, while based in a strong

Indian and Chinese tradition, found its true home in Japan.

Because of these religious ties, it is important to understand the growth

of Zen in order to properly understand the appearance of this artistic

tradition. Fortunately, it does not take long to gain an understanding

of the very practical Zen religion and, similarly, to know the origins

of the Japanese painting traditions. Additionally, suiboku often

portray similar subjects and themes; knowledge of these themes and some

of those who painted them can prove highly illuminative.

historical background

kodai art

Before the appearance of Zen art and its offspring,

kodai painting

dominated Japanese culture.

Kodai is a Japanese art history term

referring to the Asuka (552-646) and Nara (646-794) periods, though Ichimatsu

Tanaka extends this definition to include the Heian period of 794-1185

(Tanaka 9). This traditional form of art would persist well into the 13th

century, though the rise of the warrior class and especially the shogunate

would set its demise in motion (Tanaka 30).

Early kodai art was heavily influenced by the Tang dynasty (618-906)

in China, with Japanese artists producing works in a style that is largely

indistinguishable from their Chinese counterparts (Tanaka 10). Foreign

artisans composed much of and often lead the Painter's Bureau, a Nara-period

government office that formed the center of Japanese art (Tanaka 11). Such

a reliance on foreign artists is bound to slow the creation of a uniquely

national style; in fact, this foreign influence would remain strong until

the Bureau became the Edokoro (Painting Office) of the Heian court (Tanaka

11).

As the Heian period began, Japanese artists began to develop a more

uniquely Japanese style. Murals and screen paintings gave way to hanging

scrolls, and the painting style grew more delicate (Tanaka 13). The collapse

of the Tang dynasty in 906 quickly destroyed any remaining artistic internationalism,

but Japanese art would still remain only a variation on the Tang style

until the twelfth century (Tanaka 14-16).

The appearance of the Kamakura shogunate (1185-1336) marked the beginning

of the Heian decline, though kodai art remained largely unaffected

(Tanaka 16). Somewhat ironically, the arrival of the strong warrior class

actually served to strengthen the position of the kodai tradition. The

mutual antipathy between Kyoto and Kamakura spurred supporters of kodai

art to entrench themselves against those who attempted to deny it (Tanaka

31-33).

Though there was a growing denial of the old tradition, it was not until

the beginning of the Muromachi Period under the Ashikaga shogunate (1336-1568)

in Kyoto that kodai art was truly threatened (Tanaka 25). Zen temples

flourished under this shogunate, producing artists who would establish

Zen art as a new art tradition.

zen beginnings

It is important to explain the growth and ideas of Zen Buddhism in order

to properly show how this sect inspired an art form quite different from

the

kodai tradition. Japanese Zen is actually a very pragmatic religion,

despite the airs of mysticism that are commonly attributed to it; this

pragmatism, as well as the incorporation of popular beliefs, accounts for

its longevity, as it remains a powerful during theology even today (Awakawa

18).

Zen and its 'wordlessness' may be considered as old as Buddhism itself,

for legend states that it was first transmitted from Sakyamuni (1029-949

BC), the founding Buddha, to a disciple via the mere twirling of a flower

held in front of Sakyamuni's chest (Seikyo Times and Brinker 7).

Sometime after this legendary transmission of Zen, Buddhism spread into

China through the teaching of Bodhidharma (c. 440-528) (Platt). However,

even before Buddhism arrived in China, the practice of ch'an--the

Chinese term for "openness" and "contemplation" from which the term zen

is derived--was already present as early as the second century AD (Brinker

2).

Chinese Zen Buddhism steadily became quite different from the original

Indian version. Though it still emphasized the Indian practices of meditation

and contemplation, it fused with the pragmatism of Confucianism while also

drawing on Neo-Taoism's emphasis on the essence of morality (Awakawa 18-20).

This Buddhist school persisted in China until the seventh century, when

rivalry and disagreements about fundamental theological points split the

school into northern and southern components (Brinker 7). The short-lived

northern school was often referred to as "gradual" Zen, for its teachings

emphasized a staged approach of study to attain enlightenment. Southern

Zen viewed such scholasticism as an unnecessary expedient (or even a hindrance);

its followers believed that enlightenment comes suddenly, as one meditates

to shed the encumbrances on one's mind (Awakawa 16). Southern Zen is often

called "sudden" Zen because of this belief, and it was to become the Zen

of Japan (Awakawa 15).

Despite the growing importance of Zen Buddhism in China, Zen would not

reach Japan until the thirteenth century. A Tendai priest named Eisai (1141-1215)

is credited as the foremost founder of Japanese Zen after his voyage to

Sung China in 1168 and establishment of the Kennin-ji temple in 1202 (Tanaka

36). The slow adoption of Zen is reflected in the fact that early 'Zen'

temples like Kennin-ji actually had to combine Zen with more popular sects

like Tendai in order to teach it at all. Though popular with the warrior

class as a religion that denied many old traditions, Zen would not be established

as a formal sect until the fourteenth century (Tanaka 38).

During this time of solidification, a large number of Chinese Zen priests

were coming to Japan to escape the Mongol invasions of the late thirteenth

and early fourteenth centuries (Tanaka 60). They brought paintings with

them as well; many of these paintings were of the doshakuga type,

a type that used Taoist and Buddhist themes for aesthetic appreciation

instead of worship (Tanaka 61). These paintings helped promote a growing

movement in Japanese art away from mysticism and toward pragmaticism and

realism, values that Zen Buddhism (and therefore Zen art) fit easily with.

Ultimately, suiboku--monochrome ink art--grew in the hands of

the Zen monks in Kyoto. The Shokoku-ji, a leading Zen temple in Kyoto,

was established under the Ashikaga shogunate and would eventually become

the new art academy of Kyoto. The aging Edokoro declined with the non-military

aristocracy, and eventually kodai art was cast as a traditional

stereotype (Tanaka 64).

research report

As the Edokoro declined, the potential for a new art academy grew. The

Shokoku-ji would come to fill this role as several of its leading priests

made important contributions to the growth of new Japanese art forms.

artists

Josetsu was the first notable artist to appear during the Muromachi period.

Though little is known about his life, scholars have determined that he

was a priest-painter from the Shokoku-ji and was active during the early

fifteenth century (Tanaka 65). He had close ties with the Ashikaga shoguns,

and is typically credited with the founding of the 'academy' which would

produce most of Japan's early monochrome ink painters.

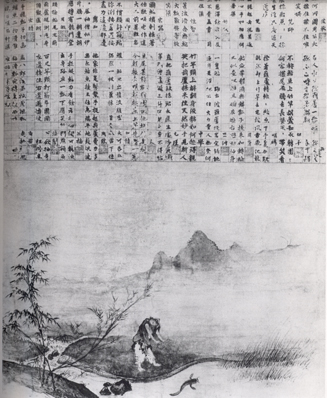

Only three works are positively identified as Josetsu's; the most noted

of these works is Catching a Catfish with a Gourd, which was painted

around 1413. This Chinese-influenced ink painting establishes Josetsu as

a seminal figure in Japanese monochrome ink painting (Awakawa 177). The

work is meant to depict the elusive nature of Zen, faring far better at

its depiction than the accompanying inscriptions (Awakawa 74 and Tanaka

65). The odd-looking man central to the painting is faced with the difficult

task of catching a rather large catfish with a rather small gourd, and

his somewhat stilted appearance lends a humorous air to the work.

Though little about Josetsu is known, even less is established concerning

Shubun, Josetsu's apparent successor and student. He is believed to have

been active from the 1430s until his supposed death at some time in the

1460s (Tanaka 70). He probably had closer ties to the shogunate than Josetsu,

serving as a professional painter and sculptor (Tanaka 68). Though a large

body of landscape paintings, many of them multipart screens, are attributed

to Shubun, no existing works have been successfully verified as his.

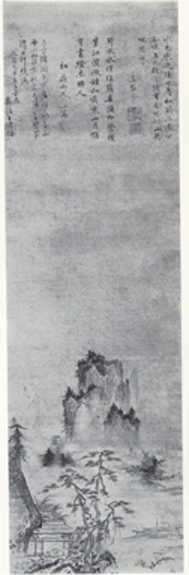

Many of these works of indeterminate ownership reveal a strong Korean

influence; this trait is not surprising considering that Shubun visited

Korea around 1423 (Tanaka 89). This influence was quickly assimilated and

altered by Shubun and his followers. However, Ichimatsu Tanaka suggests

that it may aid in pinpointing some of Shubun's works, offering Mountain

Landscape as one such probable (pp 90-91).

It is also important to note here that although Shubun was a Zen monk,

his paintings made little use of religious themes or ideas. In fact, he

left the temple fairly early in order to focus on his paintings (Awakawa

182). His allegedly prolific use of landscapes as subjects marks him as

the founder of the fully Japanese ink landscape, and his style would become

the root for ink monochrome painting during much of the Muromachi period

(Awakawa 183).

The next painter of note is significant for his formation of a style

markedly different from that of the academy-trained painters that followed

Josetsu and Shubun. His name was Sesshu, and his amazing technical ability

resulted in some of the most striking ink monochromes of the era.

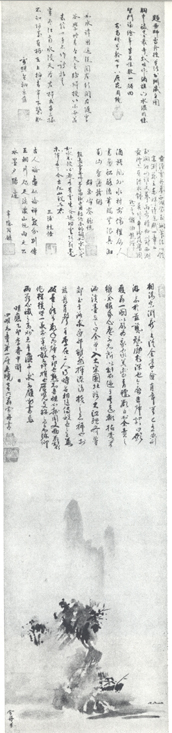

Sesshu was born around 1420 and was raised as a Zen monk, eventually

studying at the Shokoku-ji (Awakawa 180). It is likely that he was taught

by Shubun, but a journey to China from 1467 to 1469 caused marked differences

in his style (Tanaka 121). While in China, he studied the works of Sung

masters and absorbed elements of the new Yuan and Ming styles (Tanaka 128).

He was not particularly impressed by Chinese painters, however, and began

painting in a style intended to draw from reality instead of following

previous painters (Tanaka 121).

Sesshu quickly freed himself of any potential urban and religious shackles

after his return from China in 1469. He abandoned his position as a painter-priest

in Kyoto and remained in rural provinces for the latter half of his life,

but he was still an incredibly active painter despite his disconnection

from the capital (Tanaka 110). The majority of his works from this time

are landscapes, but he still painted some common Zen themes like the Bodhidharma

and Hotei.

Sesshu inspired a great number of painters and many followed his style.

Nature scenes grew in popularity and religious themes declined; however,

as Tanaka notes, Japanese paintings were still imbued with a strong spirituality

(p 137). Chinese paintings regained popularity, as did Chinese calligraphy.

Bokuseki, calligraphy by prestigious Chinese Zen priests, was highly

valued for display during tea ceremonies (Tanaka 140).

Zen Buddhism could still inspire powerful art forms, however, and the

appearance of artists like Hakuin (1685-1768) and Sengai (1750-1837) revived

the message of Zen through the painting of true Zenga pieces. In

these paintings, the essence of the painter's Zen experience is imbued

in the painting; the subject and technique are not nearly as important

as the enlightened state of the painter (Awakawa 29).

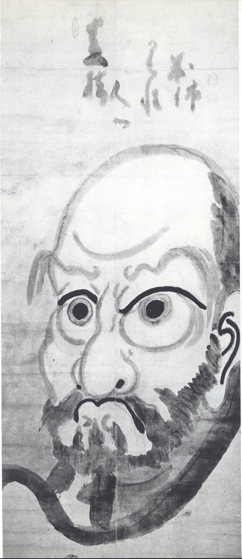

Hakuin is significant figure in both art and Zen Buddhism, as he used

Zenga, songs, and books to revive flagging interest in the religion during

the Edo period (1603-1867). He oriented his message toward the ordinary

people, an audience that proved very receptive to his paintings. He often

painted Zenga of Bodhidharma using bold lines and energetic san

writing; though his technique does not appear as refined as that of artists'

like Sesshu, it is a direct outgrowth of his Zen experience and thus transmits

his message more powerfully than more technically skilled painters (Awakawa

40).

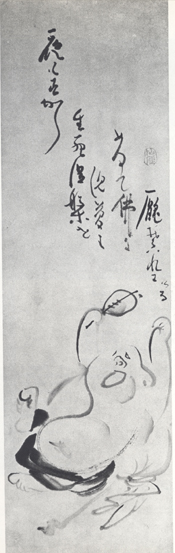

Sengai was a similarly popular figure, though his paintings are often

considered more lighthearted than Hakuin's. His Zenga are distinctive for

their use of uncommon themes and a light, almost convoluted, use of lines.

He, like Hakuin, is significant for popularizing Zen teachings with the

common people (Awakawa 180).

typical subjects

Japanese ink art, particulary Zen art, is marked by the repeated use of

common subjects. One must not conclude that Japanese art is repetitive

or unoriginal, however, as in using these common themes the artists were

able to show considerable creativity in their execution.

Perhaps the most well-known subject is the landscape. Landscape painting

is common in China and Japan, but the Asian attitude of respect (even awe)

towards the power of nature imbues these paintings with a certain spirituality

that is uncommon in Western landscapes (Tanaka 137). Landscapes were frequently

used on screens and partitions, and often repeated the landscape in for

four seasons or from different viewpoints. Other figures from nature (such

as birds, bamboo, and trees) are frequently portrayed with the same spiritual

quality and intent.

Doshakuga, or paintings on Taoist and Buddhist themes, appear

similarly frequently, even in the secular realm. A large number of figures

belong to this category, including Sakyamuni and Bodhidharma, the respective

founders of Indian and Chinese Buddhism, as well as Buddhist and Taoist

gods such as the White-robed Kannon. It is important to note here that

although these paintings are of religious figures, they typically render

the subject as quite human and devoid of many trappings of religion (Tanaka

60-62). Hotei, though he appears most frequently in Zen art, deserves a

special mention here because of his popularity as a subject: the carefree

monk with his protruding belly is often a symbol of proper Zen attitude

and denial of rules.

One other group of subjects deserves mention, and that is the koan.

Koan can be thought of as "Zen riddles," and were originally intended

as foci for Zen meditation. They can be simple-sounding questions, such

as the much-abused "What is the sound of one hand clapping?," or illustrative

events, such as when Tokusan found himself at a loss for words during a

philosophical discussion and promptly burned a copy of the Diamond Sutra.

Such paintings are far less common, as they were created only by Zen painters

and were typically only used for training new students of Zen (Awakawa

37).

the san

One may notice that a large amount of Chinese and Japanese art is accompanied

by a sometimes sizable inscription. In Japan, this inscription is called

the

san. These inscriptions are typically written by priest-friends

of the painter, though many cases exist where the

san is written

by the one who painted the picture (Awakawa 38).

Yasuichi Awakawa notes that "...the picture proper can be considered

the principle of the work, whereas the san is the application" (p

38). The inscription is oftentimes a brief description of the painting's

subject, or a cryptic comment meant to spur further contemplation. At other

times, it is a description of the artist or subject's life.

One should be careful not to dismiss the san's importance, as

both the writing and the work provide a message that neither could transmit

alone. San can provide valuable clarity, historical information,

or paths to further insight that simply cannot be expressed in the body

of the work. As Awakawa also states, "...a good san could imbue even the

painting of such an object [as a plastic bucket] with meaning" (p 40).

historical significance

The Zenga of Hakuin and Sengai are probably the works with the single greatest

historical impact, as they helped Zen Buddhism regain popularity in Japan.

Their work and their art helped to insure that Zen is still a common word

and a common concept in Japan and in the Western world.

One must also note the significance of these styles as unique Japanese

descendants of many Chinese cultural ideas. The exchange between the two

nations was significant, and Japan's culture and theology owe much to China.

However, it was never long before Chinese ideas and art forms were transformed

into something that was essentially Japanese. The suiboku tradition

and the religion that helped inspire it are certainly perfect examples

of this transformation.

references

Awakawa, Yasuichi.

Zen Painting. Trans. John Bester. New York: Harper

& Row, 1977.

Bowie, Henry P. On the Laws of Japanese Painting. US: Dover Publications,

Inc., 1951.

Brinker, Helmut. Zen in the Art of Painting. Trans. George Campbell.

New York: Arkana, 1987.

Hillier, J. R. Japanese Drawings: From the 17th through the 19th

Century. New York: Shorewood Publishers Inc., 1965.

Platt, Deb. "About Bodhidharma". 1999. URL: http://www.digiserve.com/mystic/Buddhist/Bodhidharma/index.html

Saito, Ryukyu. Japanese Ink-Painting: Lessons in Suiboku Technique.

Rutland, Vermond: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966.

Seikyo Times (author unkown). "Shakyamuni Buddha". Nov 1988. URL: http://www.ezlink.com/~dozer/fc_sgi/bios/shakyamuni2.htm

Tanaka, Ichimatsu. Japanese Ink Painting: Shubun to Sesshu..

Trans. Bruce Darling. New York: John Weatherhill Inc., 1974.

web resources

Stephen Addiss's

reflections on Zenga.

Digitized Zen

manuscripts from Hanazano University.

Mysticism in six popular

world religions.