The Boxers were a secret Chinese society bent on driving the "foreign

devils" out once and for all. No one seems to know the exact origin of

the Boxers (I Ho Ch'uan, which means Righteous Harmonious Fists); the translation

by Americans came to be known as the "boxers" (http://www.boondocksnet.com/china/.)

They may have originated in the 1700s, because Jesuit missionaries were

expelled in 1747 due to Boxer influence. Why the Boxers in 1900 were able

to garner so much influence has never been answered.

The rise in Boxer support could be attributed to the amount of imperial

support for the movement. Most notably, support came from Prince Tuan and

to a certain extent, the Dowager Empress, Tzu Hsi. This "unofficial" imperial

support of the Boxer society was not the only contribution. China had recently

suffered natural disasters as well as military, political, and economic

sanctions placed on them by the Western powers. China was defeated in 1894-1895

by Japan, with Japan emerging as the most powerful of the Asian powers.

The Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1900 is tied into a complex system of conflicts

between China and the outer world, between the central government and the

regions, between the peasants and elite. All of these conflicts compounded

each other, even though the Boxer Rebellion started in Shangdong as a movement

against foreigners and foreign influence in China, especially against the

presence of Christian missionaries. In the late 1850s missionaries were

rather free in their activities inside China, but conflicts arose in Shandong

when in 1897 two missionaries were killed, and the German government in

turn used this as an excuse to occupy the Kiaochow Bay in order to build

a German city there (Purcell, 67-81). Russia demanded and subsequently

received a lease on the ports of Port Arthur and Darien, Britain obtained

Wei-Hai-Wei, and France seized Kwangchowwan. Additionally, the completion

of the Tientsin-Peking railroad put thousands of Chinese workers out of

work. The subsequent removal of Chinese territories in the hands

of foreigners, the degredation they felt over the slights imposed by the

foreign class, as well as the drastically increasing influence of foreign

powers in Chinese culture sparked the way for a rebellion to be accepted

by the people of China.

The Boxers believed that they had been made invulnerable by sorcery

and incantation, and they began to win recruits late in 1899. Their beliefs

of resisting Europeanization to preserve the purity of the soul of China

was soon translated into a message of death to the "foreign devils" and

their collaborators. As Chinese people began to turn to these secret

societies, which had always preached hatred of the western foreigners,

the Boxers began to emerge between 1898 and 1899 from the underground and

to preach in the open. The Chinese government’s stance was initially anti-Boxer,

but eventually officials openly supported the movement. Military commanders

and governors who were anti-Boxer were removed from command and replaced

with pro-Boxers. Without restraining leadership or organization,

in early 1900 the Boxer’s began to raid outposts and symbols of western

influence, including missions. The attacks were gruesome. Men and women

were hacked to death with swords, burned alive in their compounds.

Sometimes they were dragged and tortured through howling mobs before their

execution, after which their severed heads were displayed in cages on village

gates. Between 1898 and 1899, the Boxers focused on attacking Chinese Christians,

but on December 30, 1899, they killed a British missionary (Esherick, 269-270).

The British and German governments immediately issued strong protests,

resulting in the execution of two Boxers and the imprisonment of a third.

The situation continued to worsen in early 1900, until the Dowager Empress

released an imperial edict which stated that secret societies were part

of Chinese culture and, therefore, were not criminal.

In the spring of 1900, the Boxers were out of control killing seventy

Chinese Christians and inciting riots throughout Peking. On May 29, 1900,

two British missionaries were attacked and one was killed (Sharf and Harrington,

25-30). The foreign ministers in Peking issued strong protests, and the

British diplomats informed the Chinese that they had twenty-four hours

to put down the Boxers or troops from the coast would be called in to quell

the rioting. Foreign governments immediately demanded that the Empress

Tz’u-hsi gain control over this murderous society. But the imperial court

was dominated by anti-foreign attitudes that wished to throw off the imperialistic

Western powers that, in their opinion, threatened the Chinese way of life.

This attitude dominated the government, the Boxers were not outlawed; rather

the society launched further attacks with government approval. Churches

were burned, offices destroyed, and diplomatic officials murdered. By mid-June,

foreigners and Chinese Christian converts were held in a small quarter

of Peking, while the countryside was at the mercy of the Boxers as they

slaughtered any suspected Christians. Before the Chinese government could

reply, the diplomats learned that the telegraph line between Peking and

Pao Ting Fu had been cut. The foreign diplomats ordered troops up from

the coast, but the efforts were halted by the Chinese. On May 31, the troops

were allowed to advance into Peking. Three hundred and forty troops arrived

in Peking that night, followed by another ninety troops four days later.

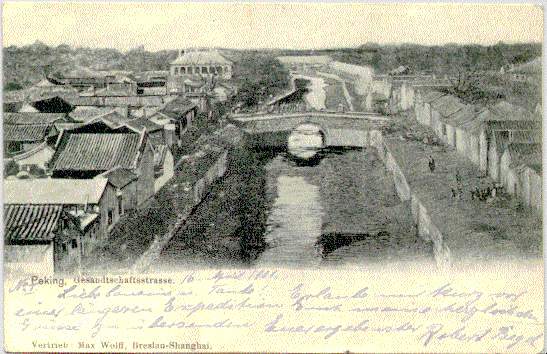

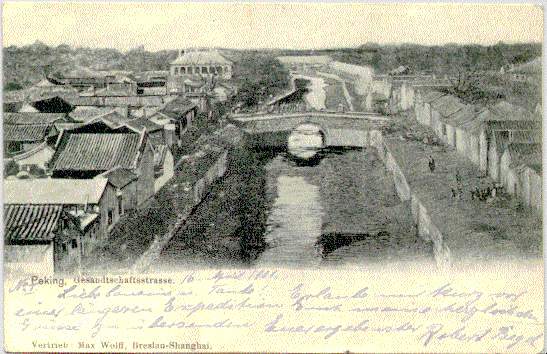

(British

Legation Quarters in Peking 1901) (British

Legation Quarters in Peking 1901)

On June 9, 1900, the first of many Boxer attacks occurred against foreign

property in Peking: the racecourse was burned down. Sir Claude MacDonald,

the British minister to Peking along with many other foreign ministers

wasting no time in lodging a protest with the Chinese government. Sir Claude

also wired Admiral Seymour at the coast to begin moving a sizeable relief

expedition up to Peking. By June 10th it was quite clear to the foreign

citizens in the Legation Quarter that

they would be the next targets of the Boxers. The Boxers cut the telegraph

line to Tientsin, stopped the mail service, collaborated with Chinese Imperial

Troops, and mounted artillery on the city walls that faced the Legation

Quarter. Additionally, Prince Tuan the new head of the Tsungli Yamen (Chinese

Foreign Office) was announced on June 10th was a noted Boxer supporter

(Sharf, 25-30).

The situation worsened the next day, when the Japanese minister was

murdered while he was on his way to greet the expected Seymour relief column.

The foreign ministers protested to the Chinese government, but the Chinese

said that it was the work of bandits and ruffians. The foreign citizens

and Chinese converts now fled to the two remaining centers of Western control

in Peking, the Legation Quarter and Pei T'ang Cathedral. The foreign ministers

had been unable to convince Bishop Favier, head of the Pei T'ang Catherdral,

to leave and come to the Legation Quarter. However, they did send

43 French and Italian sailors to defend the Cathedral.

By June 16th, Westerners and Chinese converts were in either the Legation

Quarter or the Pei T'ang Cathedral. On this day the Boxers set fire

to a large area of Peking. After the fire had been put out, there were

two very tense but uneventful days. Then on June 19th, the Chinese Foreign

Office sent an ultimatum to the Legations. The ultimatum stated that the

foreigners should evacuate Peking within twenty-four hours because the

Chinese government could no longer guarantee their safety. They offered

the foreigners safe conduct to Tientsin on the morning of June 20th (http://www.top-education.com).

All of the foreign ministers agreed that they should not move, and they

decided to buy some time by requesting an audience with the Chinese Foreign

Minister. They received no reply from the Foreign Office and the German

minister, Baron von Ketteler, decided to seek the minister in person. He

left the Legations in two sedan chairs accompanied by an interpreter. Not

far from the Legations an imperial soldier stepped in Ketteler's path and

killed him, and the interpreter fled and spread the news of his death.

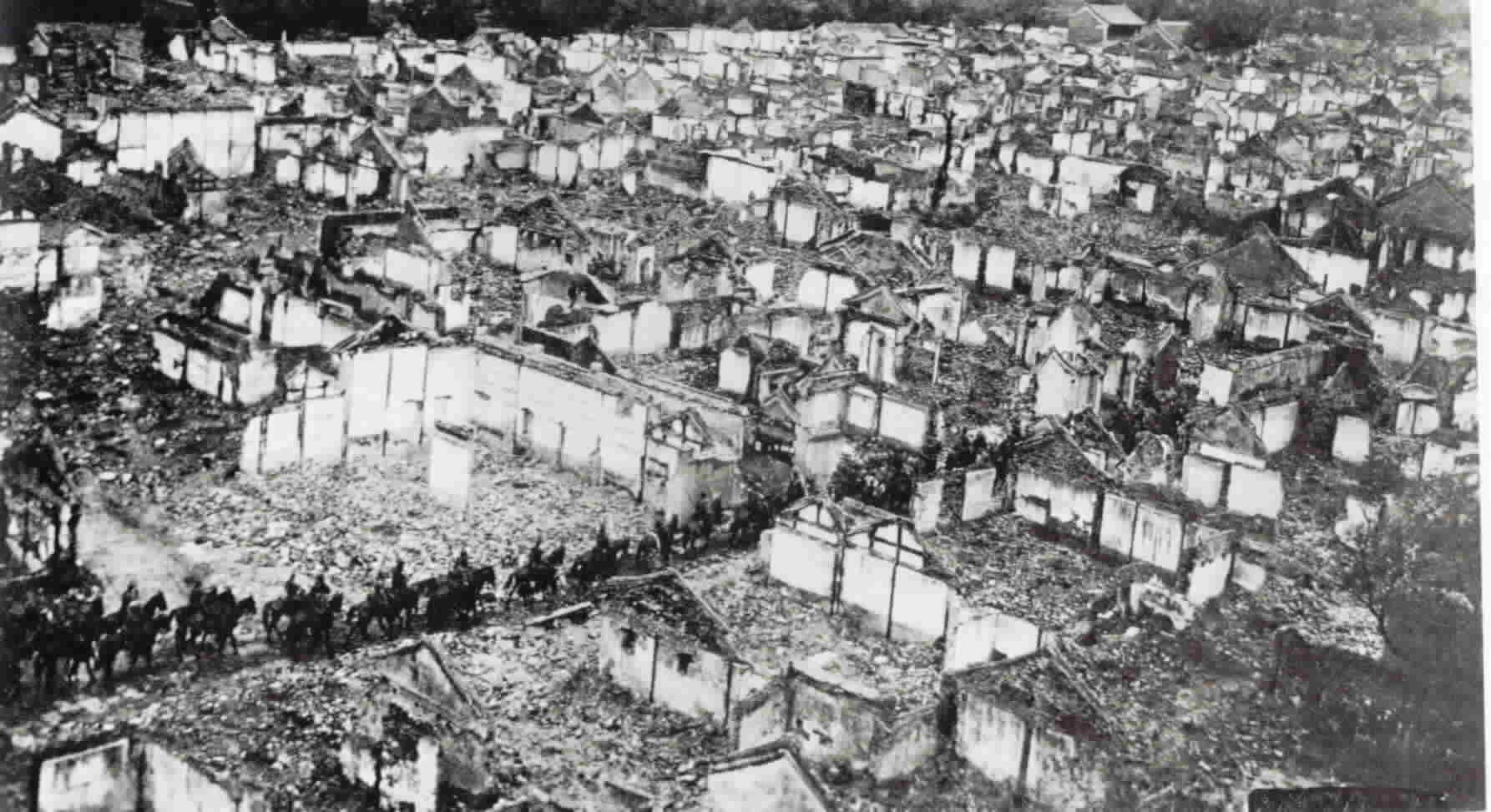

The revolt would not last. An international relief force of some nine

thousand soldiers, under the direction of the United States as well as

all of the major European powers fought its way inland from the coast.

On August 14, 1900, after Empress Tz’u-hsi fled the capital, the siege

was lifted. The world cheered as civilization was restored, but it was

hardly an enlightened ending. The foreign troops began widespread looting

of Peking and the surrounding territories in pursuit of the Boxers (http://www.mrdowling.com/613-boxer.html).

Many more Chinese civilians died due to the gunfire of both sides. While

the number of European and American loses were not small, the number of

Chinese Christian converts causalities numbered much higher, at more than

30,000.

In June 1900, Britain, Russia, Japan, the United States, Germany, France,

Italy, and Austria combined forces, and suffered initial defeats. However,

a relief expedition consisting of British, French, Japanese, Russian, German,

and American troops relieved the besieged quarter and occupied Beijing

(Peking) on Aug. 14, 1900. The US suffered 53 dead and 253 wounded in the

rebellion. The relief forces retained possession of the city until a peace

treaty was signed on September 7th, 1901. The terms of the treaty stated

the Chinese were required to pay, over a period of 40 years, an indemnity

of $333 million (http://www.regiments.org/milhist/wars/19thcent/00china.htm).

Other treaty provisions included commercial concessions and the right to

station foreign troops to guard the legations in Peking, as well as maintain

a clear corridor from Beijing to the coast. The Middle Kingdom was not

under de facto colonial rule. Despite U.S. efforts to stop further territorial

encroachment, Russia extended its sphere of influence in Manchuria during

the rebellion.

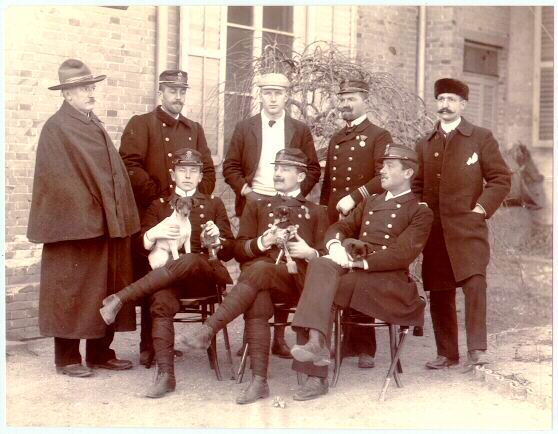

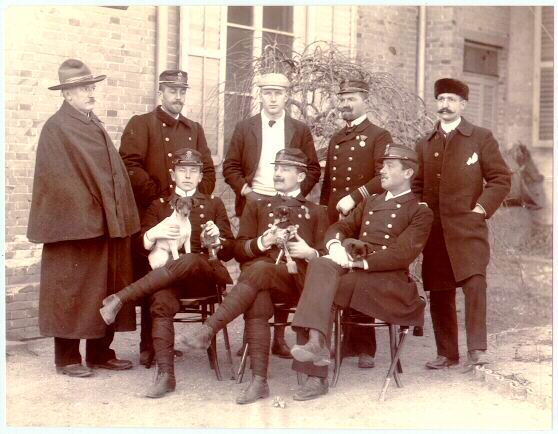

(Foreign

Troops relaxing outside their embassy in 1901) (Foreign

Troops relaxing outside their embassy in 1901)

In 1901, China was forced into virtual disarmament and fined 333 million

in reparations (which over the next forty years would double with interest)

as the official punishment for the rebellion and the loses suffered. The

cost of the Boxer rebellion, to the Chinese, was more than monetary; loses

included the collateral damage of thousands of innocent lives, territorial

loss, loss of national pride, and an even greater loss of control over

the country.

In the Boxers’ protocol signed on September 7, 1901 by eleven foreign

countries, China had to pay a high price for the 229 foreigners who lost

their lives during the rebellion. The government had to punish the

Boxers severely, suppress any signs of militant xenophobia, allow foreign

troops to be stationed at every important junction between Peking and Shanghai,

and pay the aforementioned reparations. Although in the following decades

this sum was never fully paid, an estimated 669 million taels were transferred

from China to the foreign countries involved until the late 1930s. Some

of the finest libraries and research institutes concentrating on China

and Chinese history and Chinese culture were built outside China during

these years due to the "Boxer indemnities."

|

“For the past thirty years the foreigners have

taken advantage of our country's benevolence and generosity as well as

our wholehearted conciliation to give free reign to their unscrupulous

ambitions. They have oppressed our state, encroached upon our territory,

trampled upon our people, and exacted our wealth. Every concession

made by the Court has caused them day-by-day to rely more upon violence

until they shrink from nothing. In small matters they oppress peaceful

people; in large matters they insult what is divine and holy. All the people

of our community are so full of anger and grievances that every one desires

to take vengeance”

“For the past thirty years the foreigners have

taken advantage of our country's benevolence and generosity as well as

our wholehearted conciliation to give free reign to their unscrupulous

ambitions. They have oppressed our state, encroached upon our territory,

trampled upon our people, and exacted our wealth. Every concession

made by the Court has caused them day-by-day to rely more upon violence

until they shrink from nothing. In small matters they oppress peaceful

people; in large matters they insult what is divine and holy. All the people

of our community are so full of anger and grievances that every one desires

to take vengeance”

(British

Legation Quarters in Peking 1901)

(British

Legation Quarters in Peking 1901)

(Foreign

Troops relaxing outside their embassy in 1901)

(Foreign

Troops relaxing outside their embassy in 1901)