As the Japanese soldiers marched towards Nanking, the Chinese made preparations for the battle. The military leaders knew it would be difficult to defend the city; it was bordered by the Yangtze River and man-made walls and the Japanese would not have to work hard to trap the Chinese inside. However, Chiang Kai-shek firmly wanted to defend the city; this decision may have been based more on emotion than reason, since the city held the mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen. He obviously did see the potential problems of defending Nanking, though: the capital was moved to Chungking before the arrival of the Japanese. Chiang appointed an official named Tang Sheng-chih to lead the defense. Tang and Chiang had an odd relationship and Tang had twice been exiled. However, Tang was very vocal about the need to defend Nanking against Japan and this prompted Chiang to entrust him with this task. Meanwhile, the Chinese Army had other problems. The heavy losses from the Battle of Shanghai led to a mix of surviving and injured soldiers from Shanghai and groups of soldiers new to military action. The morale was poor for these troops and desertion was frequent. Troops from Szechuan and Yunnan provinces arrived to assist in defending Nanking, but these troops were even less reliable; “there was a report from ‘a very reliable source’ that Chiang Kai-shek delayed his departure from Nanking to prevent the defection of the commanders of those units.” (Yamamoto 49) Chiang and his wife left the city on December 8, soon after the treasures of the city had been taken away by boat for safekeeping. On the same day, the entire Chinese air corps also left Nanking, leaving Tang without aerial data about the location of the Japanese troops. Foreigners in the city boarded the American boat USS Panay to escape (the boat was sunk three days later by the Japanese). Citizens who were able to also left in massive amounts. John Rabe, a German who stayed in the city, wrote on December 7 “only the very poor are still here.” (Rabe 52) Tang decided to attempt a truce with the Japanese and proposed to Chiang a three-day cease-fire, which would allow the Japanese to march in while the Chinese peacefully retreated. Chiang rejected the proposal, and the Japanese began the attack on December 10.

The Chinese were determined to fight off the Japanese, but their efforts would soon prove to be to no avail. The Japanese soldiers constantly bombarded Chinese troops, in some cases preventing the Chinese from sending injured troops to the rear of the unit. (Yamamoto 65) On December 11, Tang received word from Chiang Kai-shek that he should order the troops to retreat and that he himself should leave the city immediately. Although wary of the consequences of this decision, Tang followed orders, and his troops began to leave by 6:00 PM the following day. On December 12, the Japanese marched into Nanking. In his diary that day, John Rabe wrote that there was “Uninterrupted artillery fire from [nearby] Purple Mountain. Thunder and lightning around the hill, and suddenly the whole hill is in flames… An old adage says: When Purple Mountain burns, Nanking is lost.” (Rabe 62)

With the military retreating and the government long gone from Nanking,

control and order was placed in the hands of a group of European and American

men who had formed the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone.

The Safety Zone was a neutral area in the city which contained, among other

things, the American, German, and Japanese Embassies and Nanking University.

The head of this committee was John Rabe, the head of the Nazi party in

Nanking and an employee of the Siemens China Company. He and his

fellow committee members worked with the Chinese officials, including Tang,

in an attempt to persuade the Japanese to accept the neutrality of the

Safety Zone. In a letter to the Japanese commander, the committee

requests that they may house homeless refugees in the zone, be allowed

to operate soup kitchens, and be able to police the area with their own

civilian police. (Hsu 2) Many refugees were housed there; Rabe actually

allowed many to stay in his backyard, and his diary contains many instances

of Japanese soldiers attempting to enter his property, only to be chased

away by Rabe. Committee members also received complaints filed by

citizens about crimes occurring at the hands of Japanese soldiers—crimes

that are the most controversial element of the attack on Nanking.

With the military retreating and the government long gone from Nanking,

control and order was placed in the hands of a group of European and American

men who had formed the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone.

The Safety Zone was a neutral area in the city which contained, among other

things, the American, German, and Japanese Embassies and Nanking University.

The head of this committee was John Rabe, the head of the Nazi party in

Nanking and an employee of the Siemens China Company. He and his

fellow committee members worked with the Chinese officials, including Tang,

in an attempt to persuade the Japanese to accept the neutrality of the

Safety Zone. In a letter to the Japanese commander, the committee

requests that they may house homeless refugees in the zone, be allowed

to operate soup kitchens, and be able to police the area with their own

civilian police. (Hsu 2) Many refugees were housed there; Rabe actually

allowed many to stay in his backyard, and his diary contains many instances

of Japanese soldiers attempting to enter his property, only to be chased

away by Rabe. Committee members also received complaints filed by

citizens about crimes occurring at the hands of Japanese soldiers—crimes

that are the most controversial element of the attack on Nanking.

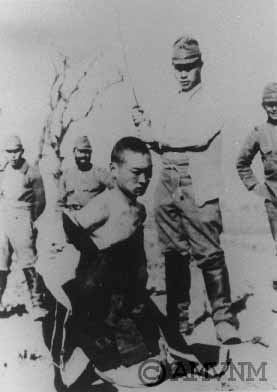

Undoubtedly, many horrifying events took place when the Japanese entered Nanking. However, the extent of these crimes has long been a subject of debate. It is apparent that many soldiers (even ones that had surrendered) and civilians were killed by the Japanese. There are stories of killing contests among the soldiers, in which Chinese were rounded up and then shot down with machine guns. Author Iris Chang tells of a man named Tang who was found by Japanese soldiers and led away to a pond with a large group of his fellow civilians. These people were lined up alongside a pit filled with corpses as the Japanese soldiers went down the line beheading their prisoners. By chance, Tang fell into the pit unharmed and was able to survive. (Chang 83-87) John Rabe’s diary contains an account of a group of former soldiers that were bayoneted and then thrown, while still alive, into a fire. (Rabe 101) The records of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone contain many more cases of murder. For example, “19. A man came to the University Hospital… He had been carrying his 60-year uncle into the Safety Zone and soldiers shot his uncle and wounded himself.” (Hsu 28-9) Also, “185. Mr. Kroeger and Mr. Hatz saw a Japanese officer and soldier executing a poor man in civilian clothes… The man was standing in the pond up to his waist in water… the soldier lay down behind a sandbag and fired a rifle at the man… the third shot killed him.” (Hsu 78) These incidents were similar to many others that occurred after the fall of Nanking. An exact number of victims, however, is hard to come by. There are burial records from various sources. If one adds up the amount of casualties from each record, the total dead in Nanking would reach about 260,000. (Chang 102) However, this number is likely to be high, since many of the records are assumed to be inaccurate. As an example of the numbers buried per group, one group, the Red Swastika Society, kept a burial record with total casualties reaching 43,071 (this figure possibly contains both civilian and military deaths). (Yamamoto 193) The true number of Chinese killed during this time will likely remain a source of controversy for a very long time if no new evidence surfaces.

While murder occurred on a large scale in Nanking, the most frequent crime committed was rape. In the Safety Zone committee’s reports, there are daily accounts of rape. Women of all ages were victimized; there are cases of rape with victims ranging from preteen to old age and everything in between, including pregnant women. As with the murders, the exact number of rape victims is impossible to establish, seeing as many of them were killed by the Japanese or took their own lives. The rapes occurred at all hours of the day, both in private and in public. Many of the cases recorded by the Safety Zone committee deal with reports of rape, for example, “18. A number of Japanese soldiers entered the University of Nanking buildings at Tao Yuen and raped 30 women on the spot, some by six men.” (Hsu 28) The soldiers sometimes inserted objects into the women’s vaginas, including sticks, a golf club, and, in one case, a lit firecracker. Young girls who were raped occasionally had their vaginas sliced open to better accommodate the soldiers, or else were raped so brutally that there was irreparable damage. The women of Nanking attempted to avoid rape; some disguised themselves as old men or pretended to be ill. Others physically fought back. One survivor from Nanking, a woman named Li Xouying, knocked herself unconscious in an attempt to kill herself and not be raped. When she awoke, she was in a basement with a soldier watching her. Instinctively, she grabbed his bayonet and fought him; when he called for help, she used him to block the bayonets of other soldiers. She was, however, stabbed thirty-seven times, including wounds to the whites of her eyes, her face, and her pregnant stomach. Li was found in time to be taken to the hospital, and while she did miscarry, she survived and still recounts her story. (Chang 97-99) Many other women were not so lucky; however, the full extent of rape will never be known.

After Nanking fell, procedures were implemented to restore some sort of order in the Safety Zone. The largest was the registration of the citizens of the city. By January 14, 1938, at least 160,000 men had been registered. The registration of women began at the end of December. The amount of order in the city was restricted by the fact that there was a lack of communication between the Japanese embassy and the military. John Rabe writes, “The officials at the Japanese embassy appear willing to make our situation more tolerable, but they also seem unable to make any headway with their fellow countrymen who happen to be in the military.” (Rabe 102) The Japanese occupied Nanking until the end of World War II, although the largest amount of crimes was over within about eight weeks of the Japanese arrival into Nanking.

In May 1946, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East began. The trial took place in Tokyo and lasted for two and a half years. Most of the blame for Nanking fell on Matsui Iwane, who was not even in the city at the time it fell. He blamed himself for the poor military guidance of General Asaka, most likely to avoid any shame falling on the imperial family. Matsui was found guilty of failing to prevent war crimes, and he was executed in a Japanese prison. Japanese Foreign Minister Hirota Koki was also found guilty on the same charge. These decisions passed by only a small majority. Radhabinod Pal, a member of the High Court of Calcutta, wrote the most detailed dissenting opinion in the trial. While he admitted that the Japanese had to have committed crimes in Nanking, he felt that Japan was victimized at the trial and that assigning war guilt to any one country requires a detailed assessment. Outside of Japan, few have considered Pal’s opinions to be of lasting importance.