|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Upon the cessation of fighting in World War I in late 1918, the

victors - the Allied forces - met in Paris to discuss the terms of peace.

The Paris Peace Conference was led by a committee called the Plenary Conference,

which represented more than 30 countries. Obviously, such a large

group of diplomats could not come to a consensus on every one of the myriad

of issues that needed to be discussed. Therefore, after months of

making little progress on the issues, the representatives from France,

Great Britain, Italy, and the United States informally created the Council

of Four. While this exclusive group did not agree on all of the topics

they discussed, the bulk of the progress made on what would eventually

become the Treaty of Versailles was made by the Council of Four.

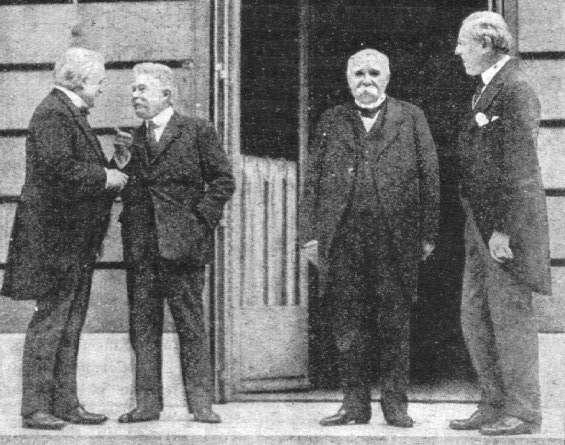

When the battles of the first World War concluded with an armistice between the Allies and Germany on November 11, 1918, the war was far from over. The aggressor, Germany, was still largely intact, while France, as one of the Allied victors, had to deal with massive territorial damage. Borders needed to be redrawn as a result of wartime occupations and newly formed countries. Perhaps most importantly, the issue of how to prevent such wars in the future needed to be dealt with. Hundreds of statesmen gathered in Paris for months to discuss these questions and other smaller, yet still important, topics. After months without progress in the Plenary Conference, the Council of Four was formed in March 1919. The group was formed by Woodrow Wilson, the President of the United States; David Lloyd George, the prime minister of Britain; Georges Clemenceau, the prime minister of France; and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, the prime minister of Italy;and brought together enigmatic personalities to struggle through important issues such as German reparations, which could not be solved by a large assembly like the Plenary Conference.

Although the Plenary Conference represented all of the Allied states, discussion was severely limited because of time concerns. Commissions were created to explore the issues in depth and to allow countries to deal with individual issues that concerned them. However, a more effective committee needed to be formed to make large-scale decisions on a timely basis. Lloyd George, Clemenceau, and Colonel Edward House, a representative of President Wilson, first met informally on March 7, 1919 to discuss a wide range of problems that could not be efficiently dealt with in the large Plenary Conference. When Wilson returned to the conference after dealing with domestic issues and Orlando joined the group on March 24, the Council of Four was created. This exclusive group of leaders resolved the majority of the issues at the Paris Peace Conference with only the help of a secretary, a translator, and the advice of expert committees.

The least influential member on the Council of Four was Orlando. Although he was formally on the council, the prime minister of Italy had little impact on many of the decisions made. Perhaps the largest reason for this was the lack of power of Italy with respect to the other “big three.” Furthermore, Orlando could not speak English - the main language used at the meetings. Lastly, he angrily left council meetings from April 21 until May 7, based upon the council’s refusal to grant Italy’s territorial demands. The issue was decided while he was away. His presence made little difference within the council, and his power was constrained.

The remaining three members were extremely influential throughout the conference. It is certain that each of them left their individual marks on the treaty that resulted. As A. Lentin claims, "If the assassin’s bullet that wounded Clemenceau in February had grazed his heart rather than his lung; if Wilson had remained in Washington … if Lloyd George had been toppled by the backbench revolt … a different treaty must surely have emerged" (105). The incredible mixture of personalities within the Council of Four was only created due to a set of extraordinary circumstances that brought about domestic calm in France, Britain, and the United States.

Clemenceau arrived at the conference desperately needing to satisfy France’s thirst for retribution against the Germans as well as regain sufficient compensation for the losses suffered during the devastating war fought on French soil. After ensuring that the peace proceedings would be held in Paris, he fought hard to become the leader of the conference, despite being outranked by the American President. He had a strong sense of his positions on the issues and even a sense of humor at times. Once he exclaimed, regarding Wilson’s Fourteen Points plan: “Fourteen points! God himself only had ten!” (Lentin 108). Clemenceau was a reasonable and clever man hampered by the tough situation of his country.

Wilson, on the other hand, had few expectations at the Paris Peace Conference from his constituents. He argued for moderation in terms toward Germany and tried to form realistic expectations within the armistice terms. Additionally, he pieced together the “Fourteen Points” - a very idealistic yet vague plan for war aims presented to his Congress on January 8, 1918. Germany contacted Wilson regarding a peace based upon these terms: therefore, he was made central to the drafting of the peace treaty.

Wilson’s Fourteen Points were mostly aimed at readjusting European borders to correct any wrongful occupation. Unfortunately, many of these ideas were not well outlined, such as his wish for “a readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality." The remainder of the Points attempt to iron out international freedom of seas, freedom of trade, military disarmament to the point of national safety, colonial readjustment, and elimination of secret alliances. His fourteenth and final Point was the general concept of the League of Nations, an international confederation of recognized countries, dedicated to protecting “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” Such clearly optimistic but undeveloped ideas made a rough base for the peace treaty with the widest implications to date. Although the Fourteen Points appealed to the defeated Germans as soft victory terms, France and Britain manipulated the same conditions to become harsh upon Germany while better for the Allies ( www.lib.byu.edu ).

Wilson’s presence in Paris heavily influenced the eventual treaty.

Although House frequently filled in for the President, their opinions did

not always coincide. In addition, House did not have the same commanding

presence as Wilson and had a tougher time convincing the prime ministers

of France and Britain to accept his positions. Wilson fought hard

to represent his positions, did not back down on crucial issues at the

heart of the peace treaty, and made intelligent compromises on matters

that could not be decided unanimously. Without his diplomacy, the

Treaty of Versailles would likely have been more of a complete devastation

of the Axis powers by the Allies, rather than the somewhat-harsh-but-still-fair

terms that resulted.

Lloyd George, the representative of Great Britain, was the fourth and

final member of the Council of Four. He, like Clemenceau, was pressured

by his countrymen to impose harsh terms on Germany for the war. This

was due to his campaign promises made during elections in the spring of

1919. Despite Britain’s relative lack of damage from the war, as

opposed to the massive territorial destruction in France, Lloyd George

was often more demanding than Clemenceau when trying to negotiate compromises

with the rest of the council, and several times deadlocked the elite committee

by refusing to back down from his demands, even though they could be unreasonable

and unrealistic. Britain’s prime minister added both significant

contributions and difficulties to the process of forming an armistice with

Germany.

The defining issue of the Council of Four was German reparations. It was not as simple as determining how much damage the Germans had caused, and forcing them to pay. The victors needed to decide whether to charge Germany for all costs or merely civilian reparations, what the value of the damage was, how much Germany could afford to pay, and how long the Germans would have to pay off the debts. These problems formed a complex web wherein no problem could near a solution without running headlong into one of the other dilemmas.

The problem with paying reparations, or compensation for repairs, as opposed to indemnities, or compensation for all losses and injuries, was that countries like Great Britain would not get rewarded at all for their participation in the war, despite making a significant difference in the tide of battle. Therefore, Lloyd George was pressed by his countrymen to get indemnities for the one million men lost by Britain in World War I while Wilson stood firm upon the belief that Germany should not be forced to pay for the costs of waging war. British Economist John Maynard Keynes outlines the situation expertly: "Mr. Lloyd George’s election pledge to the effect that the Allies were entitled to demand from Germany the entire costs of the war was from the outset clearly untenable; or rather, to put it more impartially, it was clear that to persuade the President of the conformity of this demand … was beyond the powers of the most plausible" (151). It was easier for Wilson to push for reduced reparations from Germany, given that the United States had lost only 100,000 soldiers, significantly less than any of the European nations that were preeminently involved in the war. Clemenceau, on the other hand, had to press for taking the most from Germany. Motivated by both France’s traditional hatred of Germany along with huge war debts - mostly to the United States - that needed to be paid off, the French prime minister sided with Lloyd George. However, his position was not as much from a need for German money, but rather an attempt to pressure Wilson into easing the burden of the loans on European nations.

Wilson's refusal to relent on the loan payments forced a stalemate on the issue until American diplomat John Foster Dulles suggested a compromise on February 21, 1919. His idea entailed a clause within the treaty that suggested that Germany was responsible for the war, and therefore all of its costs, but was not able to pay for all war costs and therefore would only pay partial reparations within its ability. The notion was that the populaces of Great Britain and France would generally accept the penalties, but reasonable limits could still be placed on the amount of money that Germany owed. This solution made it into the Treaty of Versailles as Articles 231 and 232, known as the ‘War Guilt’ clause.

The tasks of calculating the cost of damage and the amount that Germany could afford to pay became merged with the realization that the first number would far exceed the latter. Almost inexplicably, and contradictory to his previous stances, Wilson agreed with Jan Christian Smuts, a South African delegate, that soldiers could be considered civilian damage because “soldiers were merely civilians in uniform." One strong possibility is that Lloyd George threatened to quit the conference with the chance of receiving no recompense facing his country (Sharp 89). Regardless of the reasons why the clause was included, the cost of the war suddenly became significantly heavier upon the Germans. Early American estimates of battlefield damage ranging from £3 billion and £5 billion were countered by British approximations of £24 billion for the entire war. Wilson and Clemenceau managed to nearly agree on a figure around £7.5 billion, but Lloyd George’s supporters would not let him settle for a figure less than £10 billion, and some stood by the originally estimated £24 billion. Even after expert counsel, the Council of Four eventually deadlocked on the issue and decided to wait on naming a figure until 1921, when final surveys of the destruction caused by the war would be completed. The highest Council of the Paris Peace Conference, respected for their ability to make momentous decisions in relatively short periods of time, could come to no agreement on how much the Germans owed the Allies.

Wilson managed to limit the scope of the eventual reparations cost by forcing the Allies to set a period of time over which Germany must pay back the debts. Though it was originally agreed that the payments should stop with the passing of the war generation - generally considered to be a term of about 30 or 35 years - discussion renewed after receiving a report from an expert committee and Lloyd George objected to the interpretation that German payments were limited to the term of the payments rather than the number to be named after the Treaty of Versailles was signed. It was finally decided that 30 years would be given to complete the payments, but that could be extended if Germany needed to delay a payment in certain circumstances.

Although the Council of Four did not resolve all of the problems regarding reparations by themselves, their relatively fast decisions on such an enormous issue mark them as extremely important. If all of the issues at the Paris Peace Conference had been left to the Plenary Conference, the proceedings would most likely have taken years rather than months. The ability of the men to compromise despite being pushed and pulled in all different directions by their countrymen displays the incredible resolve of Wilson, Clemenceau, and Lloyd George. The resolution of the war reparations question can be largely attributed to these three leaders.

In conclusion, the Paris Peace Conference was dominated by the closed meetings of the elite Council of Four. Almost every important issue to be considered by the Allies passed through the hands of the leaders of France, Great Britain, and the United States. Most importantly, they decided a great deal of the debate about how Germany should repay damages caused by the war that they created. The choices made by the Council of Four would shape the face of the world to come.

Jessop, T. E. The Treaty of Versailles: Was It Just? London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd., 1942.

Keynes, John M. The Economic Consequences of the Peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920.

Kleine-Ahlbrandt, William L. The Burden of Victory: France, Britain, and the Enforcement of the Versailles Peace, 1919-1925. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, Inc., 1995.

Lentin, A. Lloyd George, Woodrow Wilson and the Guilt of Germany . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984.

Sharp, Alan. The Versailles Settlement: Peacemaking in Paris,

1919. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

The Great War - A collection of interviews and other resources used in the PBS production "The Great War."

Modern History Sourcebook: Treaty of Versailles, Jun 28, 1919 - An overview of the most important articles of the Treaty of Versailles.

Paris Peace Conference - An in-depth site covering many aspects of the Paris Peace Conference.

The Peace Treaty of Versailles - The entire text of the Treaty of Versailles and a supplementary collection of maps.

President

Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points - The transcript of Woodrow Wilson's

"Fourteen Ponits" speech.

Site Created by: David Stanton