To

Die a King

King Richard

III at Bosworth Fielde

|

King Richard III

Artist Unknown NPG 148

National Portrait Gallery London

Abstract

What’s it all about, Alfie?

The Battle of Bosworth in 1485 saw the changing

of power once more between the ducal Houses of York and Lancaster in England.

What is more relevant is how this single battle encapsulates its era and

all of the continual intrigues amongst the parties involved. Visible is

the whitewash of the victor and the modern values awarded to winning, as

opposed to, honour. Even more telling is the centuries long look back at

this time and the reign of Richard III, and the mix of fact, fiction, and

fantasy. So, shall we join the fray and see what Richard and Henry are

up to?

Historical

Background

For in this corner weighing

…

On the Redmoor Plain, south of Market Bosworth

in the Midlands of England, the sun reflected the armour into eyes. Today

was August 22, 1485 and the forces of Henry Tudor and King Richard III

quickly assembled. Their final encounter had been over two years in the

making. Ever since the death of King Edward the IV in April of 1483, the

stage had been set for a struggle for power. This new turn of events opened

possibilities both at home and abroad.

But wait. You can’t tell the

Players without a Program

Research

Report

For it is A House Divided by

The news ricocheted throughout Britain and across the English Channel.

To better understand the report of Edward IV’s death, you need to go back

thirty-some years to find the smoking gun. The Hundred Years’ War between

France and England had left England the loser. During the reign of King

Henry VI, England had lost all of her possessions in France by 1451, save

for the port city of Calais in Flanders. A weak monarchy allowed the two

major houses of nobility in England (Lancaster and York) to battle for

position as they jockeyed for prize and power. One of these clashes

was at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460, where both Richard’s father (Richard,

Duke of York) and brother (Edmund, Earl of Rutland) were killed. This led

to Richard living in exile in Flanders under the protection of Philip the

Good, the Duke of Burgundy. Next year the wind of fortune saw Richard’s

oldest surviving brother, Edward IV, proclaimed King of England over Henry

VI. Richard returned to live in England as the brother to a king. So was

the loss and gain, back and forth, rally and retreat between Lancaster

(Henry VI) and York (Edward IV).

The Royale Hatfields and McCoys

And the story continues. Nine years later, a fleet commanded by the

Earl of Warwick, the Kingmaker, and his son-in-law, Clarence (the brother

to Edward IV no less) set sail from France to reinstate Henry VI. The Spider

King of France, Louis XI, supplied the fleet in return for a promise of

an alliance between England and France against Burgundy. End result? King

Edward and Richard flee into exile to Holland under the protection of Charles

the Bold of Burgundy, their brother-in-law, who is married to Edward and

Richard’s sister, Margaret. Henry VI is released from the Tower of London

and king once more. King Henry VI was king again, but not for long. In

March of 1471, King Edward and Richard set sail from Holland with a fleet

financed by Charles of Burgundy. New results are in. Clarence switches

sides again and re-aligns with his brothers. Eight months later, King Edward

is back in London. What of King Henry VI? After conferring with his advisers,

King Edward has King Henry executed in the Tower the next day in the hopes

of ending the civil war.

Full of Spies, Spiders & Snares

So, what does this all mean? To say the least, confusing! I thank the

someone who invented surnames (last names); probably a historian or a student,

going crazy trying to keep everyone’s first names straight! By 1483, war

or the continual threat of war, in England’s internal struggle had gone

on for over thirty years. Misleading is the idea that the Hundred Years’

War is over. Only in the instance of dealing with outside enemies did the

English Houses unite. England’s main enemy, par excellence, was

France. The Hundred Years’ War was now a Cold War. A French general burned

the coastal town of Sandwich in 1457. King Edward IV had led an expedition

into France in 1475. Louis XI (remember the Spider King of France) bought

Edward off with money and a pension. Richard opposed this peace. In 1479,

busy Louis convinced James III of Scotland to violate the Scottish truce

with England so Louis could engage against Burgundy, England’s ally. Louis

could snare Burgundy in his web, while England was preoccupied with Scotland.

Edward IV designated Richard as commander of the Scottish campaign. Richard

was successful in fending off Scottish raids and even took his army into

Edinburgh.

& Brothers & Heirs

Richard was Edward’s defender and only brother. Did I forget to mention

that Edward had his brother, Clarence, executed in 1478 for treason? These

were tough times. You always needed to know who your enemies were. Spies

were everywhere. Succession of reign, the continuity to maintain control

was all-important. For Edward IV had just two sons: his first named Edward

(the heir) and his second named Richard (the spare). Richard, the Duke

of Gloucester, had one child, Edward. If you have a brother, why do you

name your son after him?

But The King is Dead. Long Live…who is the King?

All this background gets us back to April 1483. Edward the IV is dead.

Edward the V is to be king. He is a minor, 12 years old. More than likely,

Richard, the Duke of Gloucester, is to be the Lord Protector during the

minority of Edward V (the Last Will of Edward IV has not been found). Go

back in time to the last minor king, Henry VI. Henry VI’s Protector was

Richard, Duke of York, holding that office led to the Duke of York’s death

at Wakefield. The reign of a weak king meant trouble. Prone to outside

influence and international powers. Civil war and personal jeopardy. Exile,

disinheritance, and death. In light of this, a joint session of the Lords

and Commons proclaimed Edward V’s uncle, Richard, as king. Richard’s two

nephews, Edward and Richard, were no longer in the line of succession and

remained at the Tower. And from day one of Edward IV’s death, Henry Tudor

lay in wait in Brittany to make a run for the crown as well.

If others lie in wait and call

Within months of King Richard’s coronation, Henry Tudor and his force

(financed by Duke Francis of Brittany) set sail from Brittany hoping to

align with the Duke of Buckingham (another sideswitcher and Richard’s cousin)

and foment an insurrection. The insurrection fizzled like a dud firecracker

and Henry never made landfall and returned to his Brittany base. Buckingham’s

head rolled off the block, yet the threat and taint of Tudor hung like

a pall over Richard throughout his reign. The intrigues, plannings, and

plottings continued. Sporadic naval warfare ensued between France and England

in the English Channel. Trade was disrupted. Who do you trust? King Richard

surrounds himself more and more with his close circle from the North of

England. In 1484, Richard forms the Council of the North as a means to

solidify his power base. This northern power base, in turn, begins to disaffect

some of the nobles from the south. The Council of the North also limits

the power of one Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland. Richard keeps

a certain Lord Stanley close to his side. Lord Stanley (his brother is

William) is married to Margaret Beaufort. Margaret’s son by her first marriage

is none other than Henry Tudor, who now waits in exile to claim the throne.

To arms, to arms, for

By the summer of 1485, Richard knows that Henry Tudor will land an invasion

force in England. It was not a matter of if; it was a matter of when. Charles

VIII of France was supplying Henry both men and ships. France remained

an enemy of England, especially in the personage of King Richard. France

remembered that Richard had opposed the truce of his brother with France

in 1475. If Richard could solidify his reign, there was talk within court

circles of Richard’s desire to reopen the campaign against France. Aspirations

for the return of their French holdings, much less, the English claim to

the throne of France still resided in England’s heart. The Scots were engaging

England in naval battles. King Richard was the same Richard, Duke of Gloucester,

that had taken Edinburgh, and Scottish memories were long. The enemies

of before remained the enemies of today.

One Day at Bosworth

Henry Tudor King Henry VII

Artist Unknown NPG 416 National Portrait

Gallery London

When Henry Tudor landed in Wales, he had a force of about four five

hundred consisting of three thousand French and one thousand Scotch mercenaries,

the remainder being Henry’s “English” backers. As Henry advanced eastward,

he picked up some Welsh support and English defections. Richard knew of

his arrival, but delayed his preparations on August 15th to celebrate the

feast of the Assumption. His only son had died the year before. Anne, his

wife, had died in the spring. From Nottingham Castle, King Richard’s banner

waved in the wind with his motto "Loyaulte me lie" (Loyalty binds me) inscribed

on it. The royal call to arms was to meet in the Midlands at Leicester

and stop Henry’s advance to London. Richard’s kingship would be tested

once more. This was the sum of his whole life of nobility: the battles,

the successes, and losses. Loyalty was everything. Whose loyalty could

he trust?

Who’s record is about

The problem with the history concerning this battle, and its causes,

lie in the sources uncovered so far. They are either slanted (usually towards

the House of Lancaster) or unreliable. The two most memorable sources are

Sir Thomas More’s The History of King Richard the Third (More) and

William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard the third. More’s

work is dramatic literature, Shakespeare’s play is literary drama. Both

works are not considered history. This is a common consensus as drawn from

both pro and anti-Richardian scholars. Pro and con seems to size up most

of the historians who research King Richard III. Somehow, the opinion is

so polarizing that most do not occupy much of a middle ground. Additionally,

there has been some historical hanky-panky. A portrait of Richard shows

a slight hunchback. Under an infrared light, the “deformity” disappeared.

Not original to the painting, the crooked back was added to conform/confirm

to the tales of Richard's subsequent infamy. The master of the rolls (official

histories) in the Tower during Henry’s reign was John Morton, nephew to

Bishop Morton. One of the key figures in Henry Tudor’s ascension to power

was Bishop Morton. During Richard’s reign, John Rous wrote a history praising

Richard. After Henry’s coming to power, John rewrote a section, now praising

Henry and deriding Richard. An earlier copy pinpointed the changes. Although

certain aspects will forever remain a mystery, there are still new finds

through the years. A recent one is The Lovell Chronicle which gives a decidedly

Yorkist view, versus the Tudor view of the Bosworth Fielde from Bishop

Percy’s Folio. The end of the Lovell Chronicle is titled Bosworth Field

and is as follows:

(The Battle of Bosworth by Graham Turner 48" x 32" Oil on Canvas)

Bosworth Field

On this red moor

on this done day

did the last King of England

fight bravely and sway

Not meekly in fearness

nor courage a’lack

Was to traitors and treason

his Lord was attacked

By Stanley to Henry

who was but a step

By William and Welshmen

as cowards did snatch

the Kingdom of England

for Frenchmen to pat

the crown of royal

on Tudor’s schemed head

and so remove Richard

for whom they had dread

And forget not also

the man of the North

Who nary did move

nor nary sally forth

Yet the Percy who held

his hand on that day

had nary a hand

to help him when pray

he collected those taxes

of King Henry renowned

and Yorkshire remembered

his failure that dawn

and smashed him

and kil’d him

and revenged that pawn

So sadly not Scots

So sadly not Welsh

So sadly not French

did give Henry most help

Was England and English

who rescued the foes

May God have no mercy

for friends like those

For many a lies

were seeded that day

Yet weeds will come forth

of that I can pray

These writings will surface

and straighten the course

and sing the due praise

of King Richard perforce

The Knight of the Rose

Betrayed Lord of the North

I write this in haste

I write this in flight

for Henry’s spies

do see thru the night

They search me out

and wish to snuff

my life and my flame

but ‘tis not enough

For the light of the truth

will yon remember this name

Of Good King Dickon

and so fair named

King Richard the third

I dare proclaim

The Lovell Chronicle

discovered at

Sheriff Hutton Castle in

Yorkshire, England 1999

Source: The Richard Society

And as to what happened

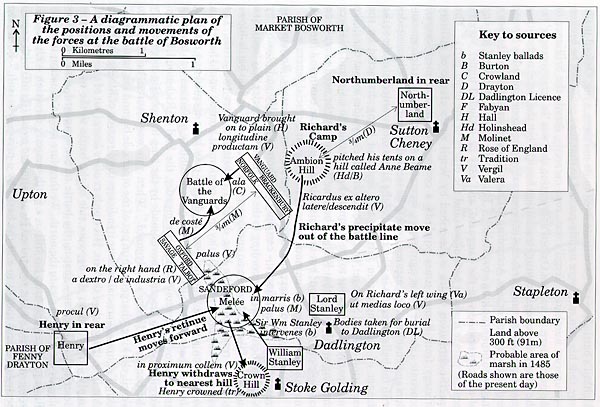

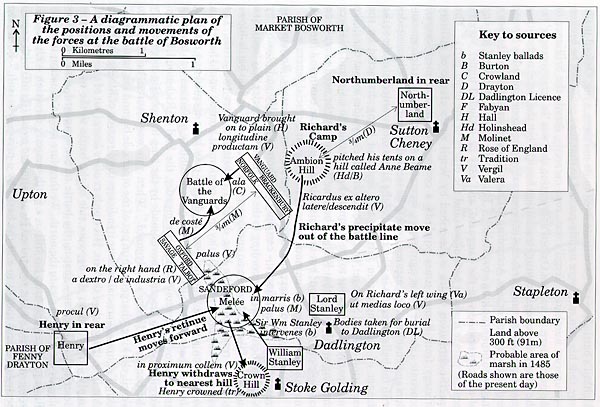

Richard had two to three times as many men in the field compared

to Henry. Richard’s army was a pooling of his various Lord's armies, whereas

Henry’s foreign retinue were paid professionals. For King Richard’s reign

began with a coup d’etat, and now he faced a coup de grace. As the armies

engaged, both Henry and Richard remained out of the fray. Richard placed

the armies of Percy in the rearguard. Lord Stanley and William Stanley

had already established themselves as the flanks. After the initial thrust,

Richard’s vanguard wavered as the Duke of Norfolk fell. Up to this time,

both Lord and William Stanley were not engaged in the fighting. Percy’s

force in the rearguard did not move. Holding off until you could determine

the possible victor and then join the winning side was a tactic that the

Stanley’s and Percy had used before. Henry and his rearguard moved in,

away from the vanguards battle, closer to William Stanley. Suspecting treachery,

Richard gambled. Drawing from his household retainers, with his crown on

his head, he led a charge directly to Henry. If Richard could cut Henry

down before any of the traitors showed their true colors, it would be over.

A trial by ordeal. Once the waverers knew the outcome of the battle, it

would be a fait accompli; and Richard could deal with the traitors afterwards.

The element of surprise could finally disperse the lingering taint on his

reign. As Richard’s band tore into Henry’s camp, the fighting was fierce.

Richard cut down Henry’s standard bearer. Just as Richard came close to

his goal, William Stanley’s men came in from the side. The Royal bee had

landed in venus's-flytrap. Now outnumbered, Richard’s knights were slain

and routed. Most of Richard’s loyal men of the North died in the field

around him. Tradition has it that Richard’s horse, White Surrey, became

stuck in the mud of a swamp as the Welshman pressed on. Richard may have

called for a horse, as he yelled, “Treason,” but it was to keep fighting.

For today, King Richard would live or die a King.

In the end

The end came from William’s Welsh pikemen, as they hacked Richard to

death. More of Richard’s troops were still on their way to Leicester, but

the battle was already over. The whole battle lasted just two hours, one

thousand men died. Henry Tudor was now King, King Henry the VII. Henry

promptly dated the date of his reign the day before the Battle of Bosworth.

Almost half of Richard’s army never engaged in the fight, at least against

the intended enemy, Henry. The naked, butchered body of King Richard was

draped over a horse and tied on like a saddle, by a rope from his neck

to his feet. Henry took his spoils to Leicester and dumped Richard in front

of the town hall for all to see. After two days, the Grey Friars of St.

Mary's buried Richard in an unmarked grave, close to the River Soar. In

contrast, the body of King Henry VI escorted by an honor guard to

St. Paul’s, was buried in the chapel of Chertsey Abbey. At the age of 32,

King Richard the III’s dreams died in the wet soil of his native England—whereabouts

unknown.

"Wer assembled in the counsaill chamber, where and when it was

shewed...that king Richard late mercifully reigning upon us was thrugh

grete treason...piteously slane and murdred to the grete hevynesse of this

citie." Council Minutes of the City of York, 23rd August, 1485

Historical

Significance

It is his story

It is about the last King of England to die in battle, the last stand

for chivalry, the end of feudalism and loyal ties, and the real end of

the Hundred Years’ War. It is about social assumptions regarding history.

Assumption: If princes disappear, then they must be dead. History is not

assuming. Perhaps this could be Thomas More’s tongue in cheek phrase regarding

history, “But of all this point, is there no certainty, and who so divineth

upon conjectures, may as well shoot too far as too short” (More, Grafton

Text 2nd ed., p. 9). In truth, aside from all of the conjectures, it is

the more universal judgement that King Richard was a failure, because he

lost. Or so it is written, or said. Forget the idea that what is written

is must be true. Whether it is in print, on the air, or on the net, know

your source. How does the source write, in what context, and by whom? Is

there an agenda? Ultimately, is the narrative real or made-up, like some

histories or Bosworth Field? For the tale is in the teller, truth be told.

Middleham Castle, Yorkshire

King Richard III's Favorite

Castle

In Memoriam

Plantagenet, Richard

"Remember before God

Richard III, King of England

and those that fell at Bosworth Field,

having kept faith.

Loyaulte me lie"

The Richard III Society

References

Bennett, Michael. The Battle of Bosworth.

Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd., 1985.

Buck, Sir George. The History of King Richard

The Third. Ed. Arthur Noel Kincaid. Gloucester: Alan Sutton

Publishing, 1979.

Hughes, Jonathan. The Religious Life of

Richard III. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd., 1997.

Kendall, Paul Murray. Richard the Third.

New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1956.

Lovell, Francis Viscount. Bosworth Field The Lovell

Chronicle. Erewhon: Imagination Press, 2001.

Pollard, A.J. Richard III and the Princes

in the Tower. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of King

Richard the third. (first edition) Ed. John Drakakis. London:

Prentice Hall, 1996.

Sutton, Anne and Visser-Fuchs, Livia. Richard

III’s Books. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd., 1997.

Tey, Josephine. The Daughter of Time.

London: Peter Davies, 1963.

Tudor-Craig, Pamela. Richard III.

London: National Portrait Gallery 27 June – 7 October 1973 London:

National Portrait Gallery, 1973.

Williamson, Audrey. The Mystery of the Princes.

Towtowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1978

Web Resources

Bosworth

Fielde. from Bishop Percy’s Folio Manuscript. Ballads and Romances Ed.

J.W. Hales and F.J. Furnivall, 3 vols. London, 1868. The Richard III and

Yorkist History Server

Kosir,

Beth Marie Richard III A Study in Historiograpichal Controversy

More,

Sir Thomas The History of King Richard the Third

Murph,

Roxanne C. Richard III: The Making of a Legend Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow

Press, 1977

Oberdorfer,

Richard Norfolk Academy Pursuing the White Boar Approaches

to Teaching Richard III

Potter,

Jeremy Good King Richard? London: Constable and Company, 1983

Site created by: James

H. Buckingham

"Not a Duke, But a King!"

Bosworth Field ©

2001 James H. Buckingham