|

Sankin Kotai System |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It would appear that the Tokugawa regime

left feudal Japan in a position that would make it hard for

modernization to take place when it opened itself to Commodore Perry

and the west in 1863. This regime closed Japan from the outside world and

allowed the society to be viewed as backward in the eyes of foreigners.

Yet there is another view that the Tokugawa regime and the institutions

created during this time in fact contributed to the development and modernization

of Japan. One such system is the sankin kotai (alternate residence), which

regulated, controlled, and to an extent impoverished the local daimyo stretching

from the northern to the southern regions of Japan. Though originally intended

as a control mechanism for the shogun, it had spillover effects that indeed

stimulated the Japanese economy and society in the Tokugawa period. Looking

more in-depth of the rules and procedures, a cost-benefit analysis, and

the socio-political and economic forces that it produced will help illustrate

how this system became beneficial to Japan’s modernization and entrance

into the Meiji and modern era.

The words sankin kotai broken down and translated to English describes this system. Sankin loosely translated means “reporting for audience or service” while kotai refers to “alternate” or “rotate in shifts”. The whole practice gradually evolved adding new components and standardizing older ones. Providing sankin was first recorded in the thirteenth century during the Kamakura shogunate. This idea was to be “applicable to any obligatory appearance by an inferior before his lord or patron to perform services” (Tsukahira, 28). Once the Tokugawa shogunate was established in 1600, the daimyo reported to Edo on a voluntary basis as a means to show homage and provide assistance to the Shogun. For example, under the bakufu system existing at the time, the daimyo were “obligated to assist on various construction and engineering projects at the capital” (Tsukahira, 40). Thus the various daimyos had to provide materials, labor, and money to aid in construction that can be financially draining.

An example of the daimyo lords’ sankin was in the construction of Edo Castle, the home of the shogun and today’s imperial family, in 1606. Since projects like this would take time, daimyo’s would occasionally depart back home and then return to the project. This was done at certain intervals, which represents the spirit of sankin kotai yet later, this idea would become not just customary, but formalized and required for all daimyo.

Later in the Tokugawa era, the Chinese character (kanji) for writing “kin” in Sankin was written with a different character that whose meaning and translation specified that it was the shogun and imperial audience who were to receive sankin duties. It became customary that those performing sankin kotai were the daimyo that had to have alternate attendance and reports to the imperial command, namely the Shogun in Edo (Tsukahira, 42). In 1610, the daimyo’s families now were ordered to send the families of their chief retainers as hostages to be housed in Edo. Thus this illustrates how the central Tokugawa government was able to control the daimyo, allowing them to be seen as subjects under him.

This customary system was formally established under the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu. This regimented system had three components. First, it issued the orders that specified how long the daimyo had to make visit to Edo. Here the time or season of the year and their stay in Edo were given out by the Shogun to these daimyo lords. Usually there were many daimyo that would enter into Edo and at the same time a number leaving Edo. Linking to this idea, the second components fixed the times that each daimyo had to render attendance to Edo and the date that they were allowed to depart back home.

Upon departure from Edo, the third mandatory component was enforced. The

daimyo lords were obligated to keep their wives and children in residence

at Edo. Reasons for all these specifications was to allow the shogun to

demonstrate a relationship of superiority and inferiority between them

and the daimyo (Tsukahira, 36). In addition, having this fixed times also

was seen as a means to control congestion in Edo allowing only certain

daimyo and their entourage to enter the city. Thus it shows that the daimyo

lords were not equal with that of the shogun. The last component first

customarily was done by the daimyo as a sense of trust and loyalty to the

shogun, but later that would change to become as a control mechanism for

the daimyo as they returned back home. In addition, this use was viewed

as a guarantee of loyal behavior to the shogun especially in those in distant

domains where these daimyo may cause uprisings or revolts against the shogun.

Therefore, this system provided a system of checks and balances, with the

shogun being more powerful and equal than the rest.

Upon departure from Edo, the third mandatory component was enforced. The

daimyo lords were obligated to keep their wives and children in residence

at Edo. Reasons for all these specifications was to allow the shogun to

demonstrate a relationship of superiority and inferiority between them

and the daimyo (Tsukahira, 36). In addition, having this fixed times also

was seen as a means to control congestion in Edo allowing only certain

daimyo and their entourage to enter the city. Thus it shows that the daimyo

lords were not equal with that of the shogun. The last component first

customarily was done by the daimyo as a sense of trust and loyalty to the

shogun, but later that would change to become as a control mechanism for

the daimyo as they returned back home. In addition, this use was viewed

as a guarantee of loyal behavior to the shogun especially in those in distant

domains where these daimyo may cause uprisings or revolts against the shogun.

Therefore, this system provided a system of checks and balances, with the

shogun being more powerful and equal than the rest.

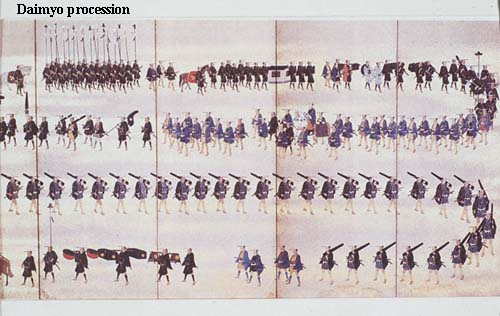

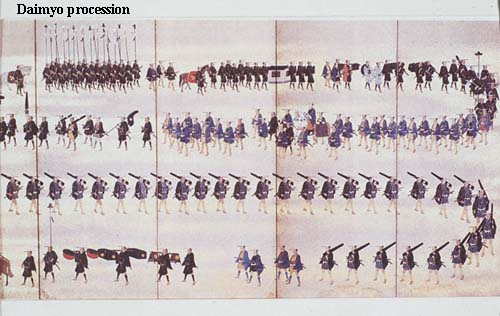

The daimyo processed from their feudal territory

onward to the shogun’s residence in Edo. In the Shoku Nihongi (Chronicles

of Japan), more detailed descriptions on how the sankin kotai was to be

done. There were two issues that were recorded. The first one stated

that “no one is allowed at his own pleasure to assemble his whole clan

within the limits of the capital”, and secondly, “no one is to go about

attended by more than twenty horsemen” (Tsukahaira, 43). This appears to

keep the daimyo from having a strong army on the journey toward Edo, which

could be a threat to the shogun’s security.

Again, the establishment of the sankin kotai was done voluntarily but

by 1651 it had become more defined as an important part of the Tokugawa

regime. By having this system of alternate residence with family hostages,

it made Edo a very important city.

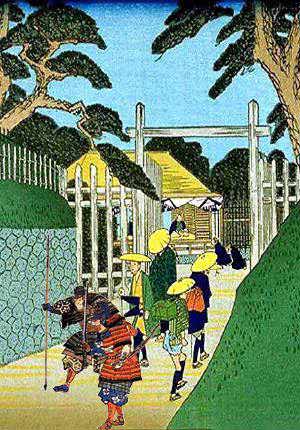

One of the ways that the shogunate regulated

and enforced this system was through the use of the Sekisho, or a guard

or checkpoint posts. These posts were placed all throughout Japan on the

major roads. These posts would check the flow of goods and people, especially

women coming in and especially out of Edo. This is because there were events

where the daimyo husbands tried to smuggle out their wives or weapons in.

This became to be known as de-onna ni iri-deppo or “outgoing women and

incoming guns” (Tsukahaira, 51). One observer of this Tokugawa culture

was a European, Engelbert Kaempfer, a young scholar who traveled from his

native Westphalian town of Lemgo eastward to Siam and on to Japan in 1690.

In his notes, he provides the mood of this Tokugawa institution:

These lords have come so much under the sway of the last shogun that they are permitted to live only six months of the year in their hereditary land, while the rest of the year they spend in the city of the shogun’s residence with their families, who reside there as hostages. (49)In one area, Kaempfer passes a sekisho, a guard post in Hakone, and provides a description of his passing through:

At the end of the town, where the road is very narrow, we stopped at a shogunal guard post, which like that of Arai, stops travelers from passing with either arms or women. But it is stronger and more important than the previous one, since this area is, so to speak, the gateway to Edo. If guards suspect a women in disguise, a thorough search conducted by a woman has to take place. (343)Through this description, it illustrates the immense control of the shogun and the very tight security enforced. Since the taking of women as hostages was essential for this control over the daimyo, it was necessary to make sure that they remain in Edo. Thus the uses of the sekisho was important, as it appears that some of the wives of the daimyo who wished for their husbands were willing to sneak out of the capital to be with them.

It is interesting to note that this system kept domestic security in check yet allowed for a greater threat from foreign forces. Thus there were many daimyo suggested reforms to the system. Yokai Shonan, a freethinking scholar from Kyushu was instrumental in altering this rigid system to allow more flexibility. Some of the necessary changes was because the sankin kotai system provided security domestically at an expense to Japan’s national defense from outside. This was because the daimyo had limited funds to defend themselves in case of a foreign attack. Instead of allocating their resources to fortify their coasts and building up arms, funds were directed toward their sankin duties (Tsukahira, 121). Thus one of Shonan’s ideas was to change the intent of the visit to Edo by the daimyo. He suggested that the daimyo only report to the capital to discuss administrative procedures. Another idea was to repeal the custom of keeping the wives and children away from the local han. Thus it appears that this was a total radical reform, transferring the idea of sankin from a controlling system toward that of a consulting group, actually assisting in policy making. Thus this reform was meant to cut the costs that strained the daimyo.

In 1862, there was indeed a reform to the sankin kotai system. The shogun summoned the daimyo who were in Edo at the time to inform them of the changes. Instead of a radical change that some advocated for, the daimyo’s obligations were just slightly lowered. The duration of their stay in Edo was reduced. In addition, they were only required to reside there once every three years (Tsukahira, 135). Some of the reforms by Yokai were addressed, as the daimyo in Edo were to submit their ideas to the shogun on how to administer national policies, address problems that they experienced locally, and provide defense ideas. In regards to the hostage situation, the reforms stated that the sons might be able to return back to their han yet they also may be required to maintain their stay as observers, rather than hostages.

Looking at these reforms, it appears that the power of the Tokugawa shogunate in the 19th century was slowly declining as power also gradually was being restored back to the daimyo. As the daimyo were freer from their sankin kotai obligations, many assembled new residences in the old capital in central Japan, Kyoto. Daimyo such as Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa used the imperial city as their headquarters as they planned a plot to overthrow the Tokugawa (Tsukahira 136). In time, the shogun and officials began to realize their mistake in giving more freedom to the daimyo and tried to reinstate the old sankin kotai system. However the many daimyo opposed the order. In addition, the Kyoto court asserted itself calling that both the internal and external situation in Japan could not sustain the sankin kotai institution. Thus, the sankin kotai system worked to centralize the power of the Tokugawa in an isolationist Japan. Once the daimyo saw that the shogun was interested in relaxing the system which is what the power system was solely based upon, it showed a decline in the Tokugawa. In addition and more importantly, many argue that once isolation was breeched, with national security in jeopardy, the system inevitably would self-destruct which formally did in 1867 (Tsukahira 137).

The sankin kotai system was a centralized system of bakufu control over the daimyo which had many impacts to Japan. An example is economic development. This first can be seen beginning with the procession from the daimyo’s lands to the capital. Many of them were directed to use certain roads, and many traveled on the Tokaido route (Oishi, 23). This route spread from the Kansai area to the Kanto plain becoming a very important and developed highway in Japan today. Since this journey would take several days, the daimyo would make many stops on this route. These stops would then grow to become post towns where the daimyo lords could relax and, have a snack, or lodge for the night (McClain, 58). With this, it helped create cities to cater to these travelers, allowing many cities to become “cities of merchants” as Osaka became during this time (Flath, 25). Moreover, with the wealthy daimyo residing in Edo for long periods of time, Edo would become a major consumption center.

In addition, those who accompanied the daimyo en route to Edo allowed the

city to grow from a tiny fishing village to a major city, with a population

of a million by the 18th century. Flath supports this by claiming that

one of the direct impacts of the sankin kotai system was the “massive migration

of persons from every part of Japan to Edo” (25). This would make Edo become

not only the largest city in the world, but also perhaps the first to reach

that many people (Nakamura, 84). As a comparison, Nakamura writes that

“neither ancient Rome nor the medieval Chinese capitals of Ch’ang-An and

Loyang ever reached a million, although it appears that Peking in the 18th

century was in the neighborhood of 800,000 to 900,000” (84). For a western

comparison, London had a population around 860,000 during this time. Although

created as a control mechanism, the sankin kotai helped transform Edo into

a metropolis and truly a uniting center for the Japanese people.

In addition, those who accompanied the daimyo en route to Edo allowed the

city to grow from a tiny fishing village to a major city, with a population

of a million by the 18th century. Flath supports this by claiming that

one of the direct impacts of the sankin kotai system was the “massive migration

of persons from every part of Japan to Edo” (25). This would make Edo become

not only the largest city in the world, but also perhaps the first to reach

that many people (Nakamura, 84). As a comparison, Nakamura writes that

“neither ancient Rome nor the medieval Chinese capitals of Ch’ang-An and

Loyang ever reached a million, although it appears that Peking in the 18th

century was in the neighborhood of 800,000 to 900,000” (84). For a western

comparison, London had a population around 860,000 during this time. Although

created as a control mechanism, the sankin kotai helped transform Edo into

a metropolis and truly a uniting center for the Japanese people.

Other additional benefits of the system were the ensured peace by keeping feudal lords in subjugation (Tsukahira, 137). Another benefit was that since daimyo lords would have consistent visits to Edo, as well as residing there for a period of time, this allowed an exchange of information from the han outside Edo as well as the exchange of the cultural ideas and developments within Edo back to the han. Tsukahira writes that the “sankin kotai served to bring a large part of leadership elements from the whole country together in one place and to keep a constant stream of leaders and intellectuals moving back and forth between the capital and all parts of the country” (3). In addition, with the processions, attendance, and the hostage situation, all have associated Edo as their home (Tsukahira, 115). Moreover, this exchange kept the central government aware of what was occurring in the han, and allowed a sense of national and cultural unity for the Japanese people. This would help stimulate in Japan’s modernization.

Lastly, the sankin journey

to and from the shogun’s residence and the local han, with sekisho’s and

post towns in place, allowed Tokugawa Japan to develop a great communication

system. Edo was the hub with the roads to the daimyo’s lands as the spokes.

All things centered around the shogun. Thus as the daimyo met with the

shogun and other daimyo, exchange of information from the han was shared.

In all, the sankin kotai added “impetus to the development of roads

and costal waterways connecting Edo and Osaka” which would help spring

up the internal economy, the rise of cities, growth of communication, and

the making Edo and also Osaka major political, economic, and cultural cities

in Japan

The costs of the sankin kotai was the financial drain it placed on

the daimyo, an economic and political cost of keeping the daimyo weak in

relation to the shogun. The journey costs alone impoverished the

local daimyo especially if they lived far from Edo. The daimyo also had

to fund their stay in Edo that became very costly especially if the terms

of residence were long. Yet this cost allowed the Tokugawa to maintain

its hegemony over Japan until 1862.

In conclusion, the sankin kotai system enabled a centralization of power of the shogun and made Edo the heart of it. Edo, renamed Tokyo in the Meiji Restoration would be a great commercial and political city as it is today. The use of this system created the development of a system of communication, spread of information, towns, and merchant citizens. It allowed Edo to the center of Japan. Perhaps this was why the revolutionary daimyo’s of Satsuma and Choshu moved the Emperor Meiji from Kyoto to Edo. Although the opening of Japan made the Japanese realize that they were backward, the internal political peace as well as the economic growth, and social and cultural developments created was able to give a sense of what essentially Japanese is. The sankin kotai was not this, nor was it intended to function as this, yet it helped that idea flourish.

Flath, David. The Japanese Economy. New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 2000.

Kaempfer, Englebert. Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed. Trans. B.M. Bodart-Bailey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

McClain, James. Japan: A Modern History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.

Nakamura, Satoru. “The Development of Rural Industry.” Tokugawa Japan:

The Social and Economic Antecedents of

Modern Japan. Ed. Chie Nakane et al. Trans.

C. Totman. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1990.

Oishi, Shinzaburo. “The Bakuhan System.” Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan. Ed. Chie Nakane et al. Trans. C. Totman. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1990.

Tsukahira, Toshio. Feudal Control in Tokugawa Japan: The Sankin Kotai

System. Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

1966.

http://hkuhist2.hku.hk/nakasendo/sankin.htm (more information on the Sankin Kotai System)

http://www.us-japan.org/edomatsu/Takanawa/frame.html (Edo life)

http://www.dentsu.com/MUSEUM/edo/travel/preface.html (Travel impacts)

http://www.us-japan.org/edomatsu/Kawasaki/frame.html (sekisho description)

http://www.ied.co.jp/isan/sangyo-isan/JS7-history.htm#_Toc442163088 (political and economic order in Tokugawa Japan)

http://www.town.nyuzen.toyama.jp/welcome/english/e001_e.htm (festivals for Sankin Kotai-Daimyo processions)

http://www.laser.ee.es.osaka-u.ac.jp/ap/1998/ob6706/obi9806/9806.html

(excerpts on the socio-tech-infrastructure brought by the Sankin-Kotai

and the end of the Tokugawa Period)

Site Created by:

Andrew N. Tenorio