|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China never wanted foreigners any more than

foreigners wanted Chinamen, and on this question I am with the Boxers every

time. The Boxer is a patriot. He loves his country better than

he does countries of other people. I wish him success.

-Mark Twain, Berkeley Lyceum, New York, November

23, 1900

The Boxer Rebellion was a movement at the turn

of the century driven by a secret society determined to drive out the foreigners

they believed to be destroying their nation. Despite the eventual

backing of the Chinese government, the movement was failure. The

combined international response that it drew served only to emphasize China's

weakness and contributed to the downfall of the imperial government.

China holds a long tradition of

being suspicious of "foreign barbarians". Their fear and suspicion

of outsiders was only increased by the events of the Opium War in 1840

and the Arrow War of 1856. The underlying purpose of both these conflicts

was to change the manner in which China carried on foreign trade.

In both cases, China was forced to submit to the will of the militarily

superior foreign nations.

However, the foreign powers

were not content to increase merely their commercial claims in China.

Their imperialist desires led them to claim many of China's colonies as

their own. Concerned with this trend, the Chinese government attempted

to strengthen the country in order to counteract the increase in Western

influence. The failure of these efforts became painfully obvious

when China suffered defeat at the hands of Japan in the Sino-Japanese War

in

1895. This demonstration of Chinese weakness left Western nations

eager to stake their claim in China. Russia, Germany, and Great Britain

all claimed Chinese ports as their own. Italy, France, and Austria

also controlled Chinese territory. The United States, whose presence

in Asia was cemented by its control of the Philippines, was so concerned

about this unchecked claiming of ports that they issued the Open Door Policy,

an effort to protect their access to Chinese markets. As these nations

fought to establish the upper hand in China, China's empress dowager, Tsu

Hsi, was searching for ways to close China to foreigners. She issued

this statement to the Chinese provinces:

The present situation is becoming... more difficult. The various Powers cast upon us

looks of tiger-like voracity, hustling each other to be first to seize our innermost

territories... we have no alternative but to rely upon the justice of our cause... what is there

to fear from any invader? Let us not think about making peace.

While the empress dowager was concerned about foreign encroachment,

Chinese peasants were more concerned with the drought, famine, and

unemployment sweeping the nation. Many of these peasants turned to

secret societies that preached hatred of foreigners. In the northern

Shangdong province, membership in a secret society known as the I Ho Ch'uan,

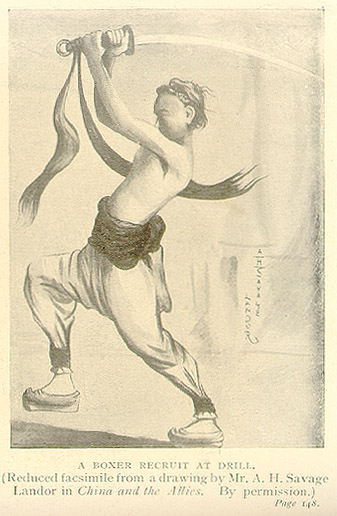

translated into English as "Fists of Righteous Harmony" was growing.

Members of this group were referred to as “Boxers”

by foreigners. They practiced an animistic magic that they believed

made them impervious to pain. This leaders of this group attracted

followers by demonstrating their “magical powers”.

They would stage elaborate ceremonies in which they appeared to be invested

with supernatural powers of invulnerability. They believed that China could

start a new golden age if it rid itself of foreigners. They were

passionate, confident, and full of violent emotion. By January of

1900, the entire Western community in China was aware of the Boxers, who

boldly stated their intentions on posted placards reading "Protect the

Empire: Exterminate Foreigners".

The Chinese imperial leadership

was initially opposed to the Boxers, and went so far as to promise foreigners

ministers that they would act against them. However the empress dowager

saw an opportunity to use the group against the foreigners. She used

her ministers to influence the Boxers, eventually supporting their actions

with provincial troops. As the year 1900 dawned, Boxers roamed wild

through the countryside, launching attacks on foreigners. They specifically

targeted missionaries and their Chinese converts, obvious examples of foreign

influence, viciously slaughtering them. The Boxers then turned their

focus to cities, their numbers growing. Nervous foreign diplomats

asked the Chinese government for help, but all they received in return

were empty promises. In the spring of 1900, Boxers killed seventy Chinese

Christians. On May 29, they killed a British missionary. Foreign

ministers threatened to call up troops if the Chinese did not put a stop

to the rebellion.

Military Escalation

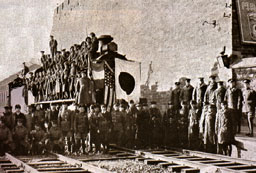

On June 9, 1900, the British Minister in Peking sent a telegram to

British Admiral Sir Edward Seymour and the British Consul at Tientsin urgently

requesting that additional troops be sent to protect the British legation

in the city. The next day, an international force of over 1, 500

men under Seymour's command was dispatched by train from Tientsin.

This force encountered hostile Boxers several times during its push towards

Peking. Eventually the expedition had to turn back, due to the fact

that Boxers had torn up the rail tracks. Seymour's force also ran

into troops from the Chinese army that had been dispatched to assist the

Boxers. As word of troops' movement towards Peking spread, riots

broke out across the country. The Chinese government readied itself

for war, viewing the additional troops as unnecessary, that foreign troops

already in Peking could provide adequate protection for the British legation.

The empress dowager called on provincial leaders to send troops to Peking,

preparing to counter foreign hostility.

At this time the Chinese government

did not intend to start a war, only to protect China from foreign aggression

and to use the Boxers in that defense. However at the same time that

Seymour's troops were making their unsuccessful movement towards Peking,

the Allied navies in the Gulf of Pechilhi demanded that China surrender

control of the Taku forts, which were of strategic importance. To

the Allies' surprise, the Chinese opened fire. An Allied landing

force quickly took control of the forts, but this incident made it clear

to all involved that the Allies, displeased with the Chinese government,

planned to mount a massive military campaign against the Boxers.

Under Siege

As the Allied forces made

their move, the situation grew increasingly worse for foreigners already

in China. On June 17th the Boxers attacked the area of Tientsin inhabited

by foreigners. Last minute fortifications installed by the foreigners

were the only things that saved their lives. All lines of communication

had been cut off, but a few brave men from the military forces stationed

in the city to protect the foreign legations risked their lives riding

their the Boxer lines to get help from the forces landing at the Taku forts.

This siege lasted for 27 days. Finally, on July 14 the Allies gathered

a strong enough force to defeat the Boxer forces and secure their base

in Tientsin.

In Peking, the capital, the foreigners

gathered at the British legation and fortified it for defense. With

the assistance of soldiers and marines stationed there for their protection,

the foreigners were able to hold off attacks from a combined force of Boxers

and the Imperial army. Maintaining the perimeter proved to be difficult

as the Chinese army brought in artillery to shell the legation. The

situation seemed so dire to outsiders that many outside of China believed

that everyone in the legation had been killed, and doubted the need for

a "rescue" mission. But the legation's defenses held, and on August

14 they were liberated by Allied

The Allies split Peking into eight regions,

each governed by a different nation. Soldiers and diplomats alike

looted the city. Troop build up continued, and the forces occupied

themselves and fulfilled their desire for revenge by eradicating every

last trace of the Boxers they could find. Anyone suspected of being

a Boxer or sympathetic to the Boxer cause was executed.

The foreign powers forced the imperial

government to agree to the terms of the Boxer Protocol in September of

1901. This agreement was a slap in the face for China, as it required

the stationing of foreign troops in the capital. It also suspended

the Chinese civil service exam, ended arms imports, and demanded a huge

indemnity. This humiliating agreement sent China on its way to radical

reforms.

While the Boxer Rebellion was an important demonstration of Chinese nationalism, it also provided the nation with a crucial wake up call. It resulted in a decline in Chinese status in the world and was detrimental to the status of the imperial government. China was forced to face the fact that its previous attempts at self strengthening had failed. After the Boxer Rebellion and the display of foreign dominance over China, the nation had no choice but to examine its traditional views and make an effort to regain its status as a force to be reckoned with in Asia. The humiliation suffered by the imperial government revealed its weakness and lessened its credibility amongst the Chinese citizenry. It demonstrated the government's ignorance and inability to control events within their own borders. This incident was another in a long string of events that forced upon China the reality of their situation. They discovered that they must modernize, in effect Westernize, in order to contend as a world power.

Buck, David D. Recent Chinese Studies of the Boxer Movement;

. M.E. Sharpe Inc,NY. 1987

Ching-shan. The Diary of His Excellency Ching-shan.

University Publications Of America, Inc, Arlington, VA. 1976.

Mackerras, Colin. China in Transformation 1900-1949.

Addison Wesley Longman Limited, London. 1998.

Sharf, Frederic A. and Peter Harrington. China 1900: The Eyewitnesses

Speak. Greenhill Books, London. 2000.

Sharf, Frederic A. and Peter Harrington. The Boxer Rebellion,

China 1900. Greenhill Books, London. 2000.

Tan, Chester C. The Boxer Catastrophe. Columbia University

Press, NY. 1955

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1900Fei-boxers.html A Chinese Christian's account

http://www.nara.gov/publications/prologue/boxer.html Military Action

http://www.wsu.edu:8080/~dee/CHING/BOXER.HTM Summary of Qing Dynasty and Boxer Rebellion

http://www.farmington.k12.mn.us/intrview/ldboxreb.htm Summary of Events

http://www.regiments.org/milhist/wars/19thcent/00china.htm Summary of Events and Military Action

http://www.lcsc.edu/modchin/u3s1p8.htm

Summary of Events