|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China faced an uncertain future following the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911. Revolutionary sentiments had been festering throughout China prior to the Wuchang Uprising that had finally ended Manchu rule over China. From this uncertainty arose the previously unsuccessful revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. Sun, who is considered the father of modern China, emerged as the leader of the rebellion that had toppled the Manchus. Sun established a new western style, republican system of government based in Nanking in 1912. Soon after being elected president, Sun realized that he did not possess the necessary control over China’s military to effectively govern. This realization led him to step down as president and name Yuan Shikai, the powerful governor of Zhili province, as his successor. Unfortunately, Yuan did not share Sun Yat-sen’s desire for a democratic government in China. Instead, Yuan extended his power as president by replacing elected officials with his loyal military leaders from Zhili. In 1914, Yuan crushed a rebellion led by Sun and proceeded to turn China into a fascist state. Yuan’s death in 1916 sent China into yet another period of chaos.

As Yuan’s military appointees fought for control of China, most of the population was left to ponder a solution to China’s woes. Hindered by internal strife as well as unwelcome foreign abuses and injustices, China’s leaders were open to several solutions. Radical ideas flourished in this environment. Marxism gradually became a viable idea in China, following the success of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the encouragement of Chinese communists by the Soviet Comintern. Nationalism was also heightened at this time. Under the leadership of Sun Yat-sen, nationalism thrived as his Three Principles of the People (nationalism, democracy, and people’s livelihood) gained popular support. As major warlords continued to fight for power, communist and nationalist activists prepared to bring order to the country. After the death of Sun Yat-sen in 1925, it was Chiang Kai-shek who was poised to take control and reunify China.

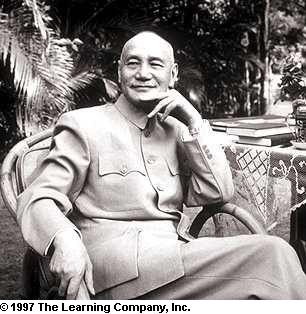

Chiang Kai-shek was born on October 13, 1887 in Chekiang Province.

His merchant family was fairly wealthy, yet Chiang endured certain hardships

that shaped his personality. His father, who he rarely referred to

and apparently was not fond of, died when Chiang was eight years old.

Chiang's young life would be shaped by his mother and grandparents, both

of whom he would love and give praise to in his later life. As a

boy he was tutored and learned about the views of Sun Yat-sen, as well

as the values of Confucianism (Crozier, 34-35). This, as well as

his military training, would provide the foundation for Chiang's life as

a revolutionary and leader of China.

Chiang began his military career after passing a competitive examination to gain entrance to the Paoting Military Academy in 1906. Soon after, Chiang was selected to travel to Japan and study military science at the Preparatory Military Academy in Tokyo. Beyond the significant military skills and lifestyle he would acquire in Japan, Chiang developed in a number of important ways. Most importantly, his previous knowledge of Sun Yat-sen was cultivated as he was introduced into a revolutionary group by some of his peers. As a member of the Tungmenhui (Alliance Society), Chiang was introduced to Sun Yat-sen. Deeply impressed by Sun, Chiang continued to develop as a revolutionary, eventually devoting his entire life to the Nationalist cause (Crozier, 37-38).

Attracted by news of revolution in China, Chiang returned home and was involved in the rebellion that overthrew the Manchu dynasty in 1911. After the founding of the KMT government in Nanking in 1912, Chiang witnessed Yuan Shikai's abuse of the new republican China against the wishes of Sun Yat-sen. As a devoted follower of Sun, Chiang participated in the failed Second Revolution. Described as "impulsive and adventurous," Chiang attempted to start several uprisings against Yuan. Although he was defeated on a number of occasions by Yuan's forces, Chiang's status in the eyes of Sun constantly improved. By some accounts these tribulations led to Chiang becoming quite close with Sun (Crozier, 42-46). After the ultimate failure to defeat Yuan, Chiang slipped into the underworld, apparently joining a secret society in Shanghai called the Green Gang. Yet when Yuan died in 1916, Chiang returned to action as Sun Yat-sen began to organize the KMT against the warlords who had a chaotic stranglehold on China.

Chiang was to play an integral part in the KMT's move to oust the warlord government that was based in Beijing. In time, he would become the military leader of the Nationalists. Representing the conservative branch of the party, Chiang advocated a strong military and a centralized government that would reunify and stabilize China. His rise to the top of the KMT began as he languished in Canton amidst the chaos of revolutionary change. As a KMT military leader in Canton, Chiang developed his conservative views. Gradually, Chiang gained influence in the party and in 1923 was sent to the Soviet Union to study the practices of the Red Army. Soon after his return he became the superintendent of the Whampoa Military Academy. This would prove to be the key to his control over the military and vital to his position as the future leader of the KMT.

Following Sun Yat-sen's death in 1925, Chiang essentially was the leader of the KMT, as he had control over the military. Enthusiasm for Marxism was growing in China and the Chinese Communist Party (set up in 1921) was bolstered by Soviet support. Unknown to most people at the time, Chiang had returned from Moscow with a dislike for the Soviets and communism (Crozier, 72). Despite this, Chiang decided to utilize Soviet support for his own goals and cooperated with the Communists. Soon the Nationalists forged an alliance with the Communists, established the Wuhan government in the south and prepared to challenge the warlords.

Realizing it had managed to secure southeast China, the Nationalists, under Chiang's military leadership, launched the Northern Expedition against the warlords in 1926. Chiang faced a number of obstacles in moving north and eventually conquering half of China. He faced several major warlords and a number of independent forces as he made his way north. By shrewdly manipulating the Communists to take advantage of Soviet support, Chiang managed to make significant progress in achieving his hero Sun's goal of reunifying China. Yet he also had to pacify more conservative members of the KMT who, like him, disliked the Communists and wanted them out of the party. Despite the alliance's success, a rift developed between the CCP and the KMT. Once the CCP was advised by Joseph Stalin to cooperate, the expedition continued and the alliance captured Shanghai. At this point, the Communists believed they had Chiang in the perfect position. He had led his forces and had reunified most of China. Planning to oust Chiang and establish Communist China, the CCP was preempted by Chiang's decision to liquidate the Communists. On April 12, 1927, Chiang launched the White Terror. This operation involving his army and connections in the Chinese underworld eliminated eighty percent of the Communists in China. In 1928, the KMT under Chiang also captured Beijing from the warlords. In a relatively short time, Chiang had successfully reunified the country and was now the leader of the Nationalist government in Nanking (for more information on the KMT government in Nanking, click here.)

Although Chiang and the Nationalists would rule mainland China from 1928 until 1949, this would prove to be a trying, and ultimately unsuccessful period for Chiang. Several obstacles prevented the KMT from implementing social programs, which would possibly have helped China progress after nearly twenty years of fighting and chaos. Obsessed with eliminating the threat of Communism in China, Chiang constantly dealt with the remnants of the White Terror. Communism had survived in China and would eventually rise up under Mao Zedong (who was organizing peasants in the rural areas of southern China) and defeat Chiang. China also was threatened by an ever-dangerous Japan, which had aspirations of moving into China, having already taken Manchuria in 1931. More concerned with the Communists than Japan, Chiang was criticized by many and eventually was forced into fighting a long war with Japan. In response to these and other problems that threatened his relatively new government, Chiang initiated the New Life Movement in 1934. Borrowing ideas from Confucianism and Sun's Three Principles of the People, the campaign was designed to bring spirit and cohesion to China (Hsiung, 315, 361-372).

His troubles with Japan and the Communists came to a head in 1936 with what is called the Sian Incident. Angered by Chiang's reluctance to deal with the Japanese threat in the North, Chiang was captured by one of his own generals, Chang Hsüeh-liang. Chang commanded the northern forces of the Nationalist army and arrested Chiang when the leader visited Sian in December. While imprisoned, the Communists formed a new alliance with some Nationalists in opposition of Japan. Chiang was forced to accept the situation and was released on Christmas Day. This humiliation damaged Chiang's reputation and was a precursor to the reawakening of the Communists in China (Crozier, 181-189).

With anti-Japanese sentiments now officially declared by the new alliance, Japan was eager to attack China after forging an alliance with Germany. War with Japan, which began in 1937, would prove costly as China fought on its own for four years before receiving help from the Allies. When World War II ended, China was included among the major winners, along with the United States, Britain, and Russia. This victory for Chiang would be short lived, as he would soon face a civil war with the Communists for control of China. By failing to confront the Japanese and allowing his Nationalist forces to become passive, Chiang allowed Mao to capitalize on feelings of nationalism as the Communists resisted the Japanese. Chiang's government has been historically accused of being corrupt. Chiang himself has been criticized for being inflexible and decreasingly aware of public sentiment. Ultimately, Chiang made too many crucial mistakes at the wrong times, usually involving his desire to eliminate the Communists. For these, and several other reasons, Chiang was "the man who lost China" to Mao Zedong and the Communists (Crozier, 390).

Perhaps it is some consolation to Chiang's historical stature that the idea of Nationalist China continues to survive in the face of the massive People's Republic of China. Chiang and his followers established a new government on Taiwan after being ousted from the mainland in 1949. A changed (and likely discouraged) Chiang led Taiwan as it developed into a modern economic power in Asia. The government was reformed, which was undoubtedly easier to do on such a smaller scale and without the constant threat of Communist influences. For over twenty years, Taiwan benefited from military protection and aid from the United States and was even recognized as the official China, holding a seat in the United Nations. Bolstered by these successes, Chiang and the KMT were hopeful in posing a renewed challenge against the Communists. Yet in 1971, Taiwan was thrown out of the UN and a gradual improvement in relations between Communist China and the U.S. diminished this possibility. Although angered and disappointed by these developments, the KMT led Republic of China adapted and gradually progressed. This final disappointment effectively ended Chiang's reign as the leader of Taiwan. Although still officially the president, Chiang was effected by old age and increasingly withdrew from public life, spending most of his time secluded with family until his death on April 5, 1975 (Crozier, 382-385). Chiang Kai-shek had been the leader of Nationalist China, both on the mainland and on Taiwan for 47 years.

Chiang Kai-shek has been both praised and criticized for his actions

as the leader of Nationalist China. He can be lauded in many ways

as: the reunifier of China, a staunch opponent of communism, and a skilled

military leader. Yet he has also been negatively appraised as both

a fascist dictator and inept leader of a corrupted and ineffective KMT

Party. Some even refer to him as "the man who lost China" (Crozier,

viii-ix, 1976). While Chiang's status as a leader in the annals of

history may be mixed, it seems certain that he had a profound impact on

the history of modern China in several ways. First, as the successor

to Sun Yat-sen in the Nationalist Party, Chiang used his military power

and shrewd political skills to fight and defeat the warlords that had torn

up China. This victory, along with the institution of the new Nationalist

government provided China with a foundation for unification and stabilization.

Chiang is also historically significant for his failure to maintain Nationalist

control of mainland China. His inability to completely wipe out several

problems (such as the warlords, foreign influences, and most importantly

the Communists) allowed the Communists to overtake Chiang. Finally,

his leadership of the KMT on Taiwan is also important for many reasons.

While unable to pose a significant threat to retake the mainland, Taiwan

did develop into an economic power in Southeast Asia and until recently

was more prosperous and had more potential than mainland China. In

addition, Taiwan's struggle to be the officially recognized China was and

still is a major international issue. The institution and development

of the Nationalists on Taiwan is historically significant and possibly

Chiang's most enduring legacy. Whether hailed as a nationalistic

and heroic re-unifier of China or reviled as a murderous, ineffective dictator,

Chiang Kai-shek remains one of the most influential and important figures

in Chinese history.

Crozier, Brian. The Man Who Lost China. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1976.

Hahn, Emily. Chiang Kai-shek. Garden City: Doubleday

and Co., 1955.

An unauthorized biography

of Chiang Kai-shek, written soon after his defeat by the Communists.

Hsiung, S.I. The Life of Chiang Kai-shek. London: Peter Davies, 1948.

Kai-shek, Chiang. The Collected Wartime Messages of Generalisimo

Chiang Kai-shek.

Chinese News Service, 1943.

Loh, Pichon. The Early Chiang Kai-shek. New York:

Columbia University Press, 1971.

An interesting insight into

the formation of Chiang Kai-shek's personality. Special attention

is given to his childhood and relationship with his parents.

Sainsbury, Keith. The Turning Point. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1985.

Discusses Chiang Kai-Shek's

involvement in World War II with the other key Allied powers.

www.maoism.org/msw/vol4/mswv4_20.htm

Contains

documents illustrating Mao Zedong's opposition to Chiang Kai-shek and the

Nationalists.

www.time.com/time/asia/asia/magazine/1999/940823/cks.html

Interesting

article about Chiang Kai-shek as one of the most influential Asians of

the 20th century.

www.taiwandc.org/history.htm

Information

about Chiang Kai-shek and Taiwan from the Republic of China's perspective

www.wsu.edu:8001/~dee/MODCHINA/NATIONAL.HTML

Informative page about Chiang Kai-shek's ideas, The Northern Expedition,

and the structure of the Nationalist government in Nanking.

www.newton.mec.edu/Angier/DimSum/Chiang%20Kai%Shek.Bio.html

www.york.cuny.edu/~clip/student/yeh_h/lifefile/lifefile.html

Both

are short biographical summaries of Chiang Kai-shek's life.

www.britannica.com/seo/c/chiang-kai-shek

Site created by: Andy Lambrecht