Chinese

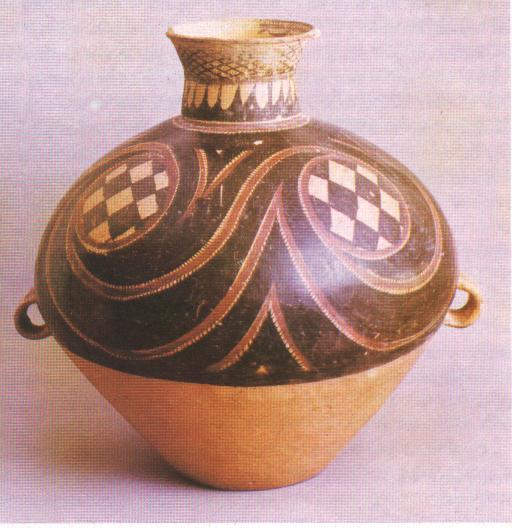

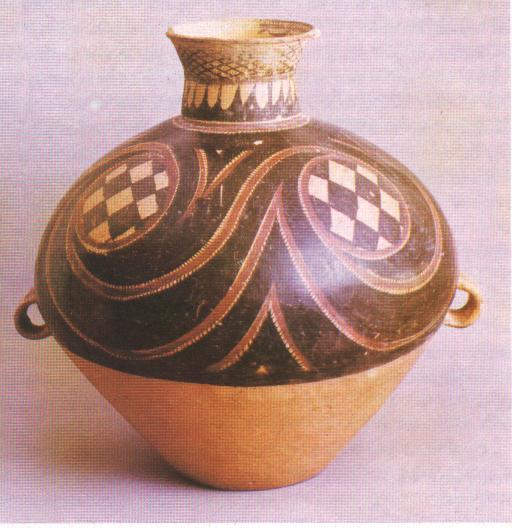

ceramics began with the people of the Yangshao culture in about the year

5000 B.C. near the Wei River. Two major types of pottery were made

at this time. The first was gray everyday earthenware that often

was minimally decorated with “cord, mat, or basket impressions” (Blunden

53). The second type of pottery is more intricate as well as beautiful.

These earthenware pots have a “lightly burnished surface decorated with

painted designs in black, red, maroon, and brown” (53). The decorations

are generally simple geometric patterns such as swirls, but they can be

more ornate and include stylized fish, birds, and human faces (Gernet 39).

As the culture spread westward, the pottery “from the Kansu sites…displays

more elaborate designs” (39). This type of highly decorated pottery

seems to have been used primarily for funerary practices. Chinese

ceramics began with the people of the Yangshao culture in about the year

5000 B.C. near the Wei River. Two major types of pottery were made

at this time. The first was gray everyday earthenware that often

was minimally decorated with “cord, mat, or basket impressions” (Blunden

53). The second type of pottery is more intricate as well as beautiful.

These earthenware pots have a “lightly burnished surface decorated with

painted designs in black, red, maroon, and brown” (53). The decorations

are generally simple geometric patterns such as swirls, but they can be

more ornate and include stylized fish, birds, and human faces (Gernet 39).

As the culture spread westward, the pottery “from the Kansu sites…displays

more elaborate designs” (39). This type of highly decorated pottery

seems to have been used primarily for funerary practices.

From a more mechanical and less aesthetic viewpoint, the Yangshao potters

began the long tradition of combining function, form, and painting into

their ceramics. The Yangshao had a small repertoire of shapes that

included bowls and jars. The usual baking temperature was 1000-1500°C

(39). Both the coarser gray ware and the highly burnished pottery were

hand built. The gray ware was built “with coils of clay, and smoothed

over to conceal the joins” (Blunden 53). The burnished pottery was

built up in a similar fashion but was of a higher quality of workmanship.

Much of the decoration on the burnished pottery was painted on with slips,

which are solutions of metals. The Yangshao used “colours deriving

from iron and manganese producing black, dark brown, and maroon.

A later addition was the white slip which heightened the decoration in

a striking manner” (Hook, 387). From these discoveries, decoration

blossomed, and even in this early time of Chinese culture embellishment

upon the pottery was “highly stylized, yet it exhibits the vitality and

rhythm which is to characterize all Chinese art” (Morton 12).

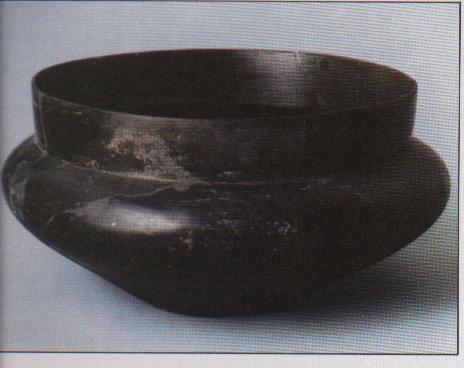

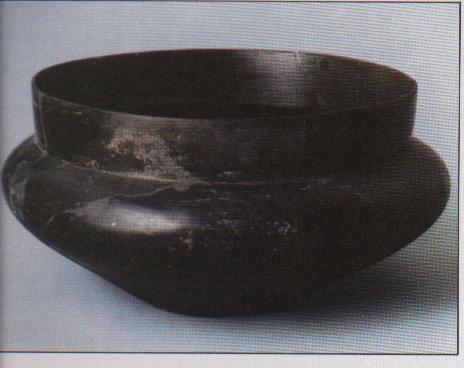

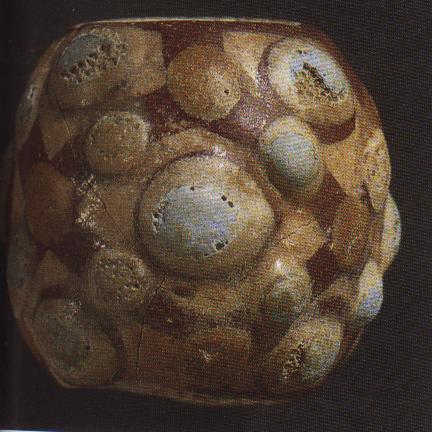

Types of pottery are the central division among Chinese Neolithic cultures.

The Yangshao, as described above, had two main types, with the burnished,

highly decorated pottery being the hallmark style. Following the

Yangshao is the Longshan culture, beginning in approximately 4500 B.C.

and overlapping with the Yangshao for 1500 years. The Longshan were

generally farther east compared to the Yangshao, but some excavation sites

have the Longshan directly succeeding the Yangshao. Like their predecessors,

the Longshan had two types of pottery, but only one is studied with great

care. The Longshan share the more functional gray wares with their

predecessors. The key difference between the cultures is the Longshan

blackware. There are some immediate differences from the highly decorated

Yangshao pieces. First, the Longshan wares are significantly thinner

due to the fact that the vessels were thrown on a potter’s wheel rather

than built by hand. This may have been a consequence of being farther

east and having more contact with the Koreans. Second, Longshan pottery

is has no decoration. These blackwares were made by firing the iron

poor clays initially and then exposing them to smoke. The smoke could

be “penetrated deep into the hot porous ceramics, turning them a fine black

colour- a process known as carbonizing. If the ceramics had been

burnished before firing the result was a deep and glossy black” (Wood 14).

Another major difference in the Longshan pottery is its form, which is

“angular in outline and extremely elegant…Some shapes are already close

to those vessels of the Bronze Age”(Gernet 39). Although the Longshan

culture ends around 2500 B.C., there are no new defining styles of pottery

until the Shang dynasty of 1766 B.C.

Types of pottery are the central division among Chinese Neolithic cultures.

The Yangshao, as described above, had two main types, with the burnished,

highly decorated pottery being the hallmark style. Following the

Yangshao is the Longshan culture, beginning in approximately 4500 B.C.

and overlapping with the Yangshao for 1500 years. The Longshan were

generally farther east compared to the Yangshao, but some excavation sites

have the Longshan directly succeeding the Yangshao. Like their predecessors,

the Longshan had two types of pottery, but only one is studied with great

care. The Longshan share the more functional gray wares with their

predecessors. The key difference between the cultures is the Longshan

blackware. There are some immediate differences from the highly decorated

Yangshao pieces. First, the Longshan wares are significantly thinner

due to the fact that the vessels were thrown on a potter’s wheel rather

than built by hand. This may have been a consequence of being farther

east and having more contact with the Koreans. Second, Longshan pottery

is has no decoration. These blackwares were made by firing the iron

poor clays initially and then exposing them to smoke. The smoke could

be “penetrated deep into the hot porous ceramics, turning them a fine black

colour- a process known as carbonizing. If the ceramics had been

burnished before firing the result was a deep and glossy black” (Wood 14).

Another major difference in the Longshan pottery is its form, which is

“angular in outline and extremely elegant…Some shapes are already close

to those vessels of the Bronze Age”(Gernet 39). Although the Longshan

culture ends around 2500 B.C., there are no new defining styles of pottery

until the Shang dynasty of 1766 B.C.

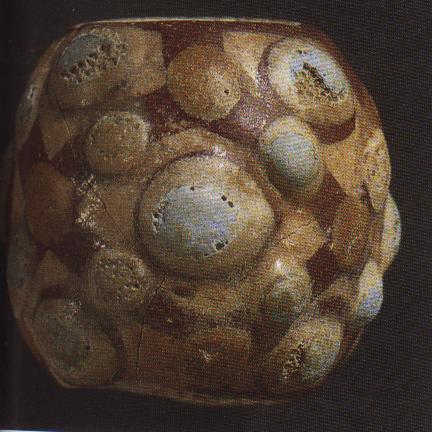

The Shang dynasty is considered a part of the Chinese Bronze Age and

therefore ceramics during this time period are generally not spectacular.

Nigel Wood, an expert of Chinese ceramics, states, “Ceramics from China’s

early Bronze Age are generally considered inferior, both in design and

finish, to the Neolithic ceramics” (14). Wood suggests that the quality

decreased because of the increased use of bronze vessels in rituals and

mortuary practices. Instead of showcasing a particular style of pottery,

the coarse gray ware with cord markings continued to dominate, and much

of the ceramic wares found from the Shang are molds for bronzes.

Very

much like the Shang dynasty, the Zhou dynasty (1027-221 B.C.) did not put

great emphasis on their ceramics. Once again the simple, coarse gray

wares were the main type of pottery produced. The Zhou dynasty did

craft some unique wares including glazed stoneware that was decorated by

both painting and dipping. The wares of the Eastern Zhou (771-221

B.C.) tend to follow the fads of the bronzes because they were an inexpensive

alternative to the bronze vessels used in rituals. These “bargain”

funeral wares of the Warring States period were often made from “fine siliceous

stoneware clays with yellowish, greeny-gray, or dark brown glazes” (Wood

20). The end of the Zhou dynasty marked an important change in China’s

history because the dynasty to follow was the first to unite all of China,

so technically the first truly “Chinese” ceramics were produced during

the Qin. Very

much like the Shang dynasty, the Zhou dynasty (1027-221 B.C.) did not put

great emphasis on their ceramics. Once again the simple, coarse gray

wares were the main type of pottery produced. The Zhou dynasty did

craft some unique wares including glazed stoneware that was decorated by

both painting and dipping. The wares of the Eastern Zhou (771-221

B.C.) tend to follow the fads of the bronzes because they were an inexpensive

alternative to the bronze vessels used in rituals. These “bargain”

funeral wares of the Warring States period were often made from “fine siliceous

stoneware clays with yellowish, greeny-gray, or dark brown glazes” (Wood

20). The end of the Zhou dynasty marked an important change in China’s

history because the dynasty to follow was the first to unite all of China,

so technically the first truly “Chinese” ceramics were produced during

the Qin.

The Qin dynasty was extremely short, only fifteen years, lasting between

221 and 206B.C. Obviously this short amount of time was not enough

to create a unique style of ceramics or glaze, but the Qin dynasty is noteworthy

because of the tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of China.

Qin Shi Huangdi’s tomb is outfitted with an entire division of infantry

and cavalry that consists of over “7,000 life-size earthenware soldiers

equipped with real weapons, real chariots, and pottery horses” (Huang 37).

The tomb is an awesome archeological find due not only to its size, but

also its accuracy. Each soldier has a unique facial expression, hairdo,

armor, and stance. Qin Shi Huangdi’s tomb represents a breakthrough

in production of earthenwares and showcases the creative capability of

thousands of anonymous artisans.

The Han dynasty (202 B.C.-220 A.D.), which follows the Qin, exhibits

an intriguing dichotomy because great unity and peace was brought to China

with the establishment of the new dynasty, yet the Han’s most important

contribution to the history of China’s ceramics is the fact that this time

period brings about the first noticeable difference in Northern and Southern

wares. According to The Cambridge Encyclopedia of China, “In

the north lead-glazed ceramics tended to be simply cheap substitutes for

bronzes and intended for tombs, but in the south ceramics were developed

more in their own right”(Hook 404). The common wares were often red

or gray with high-fired glazes. Wares used for funerary purposes

often used glazes that were “reminiscent of bronze in its various states

of patination and early Han lead-glazed vessels often followed the shapes

of Han bronzes” (Wood 191). Han discoveries were the early prototypes

for glazes used during the Tang and Song dynasties in sancai wares.

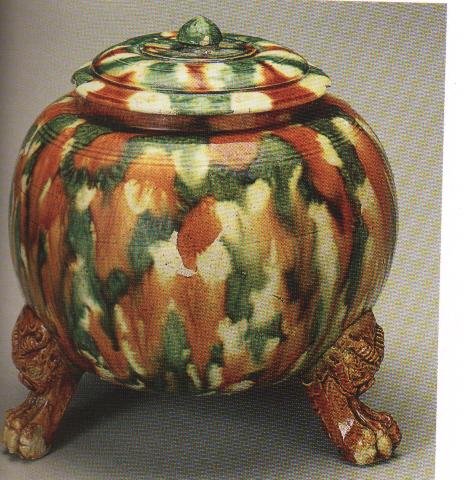

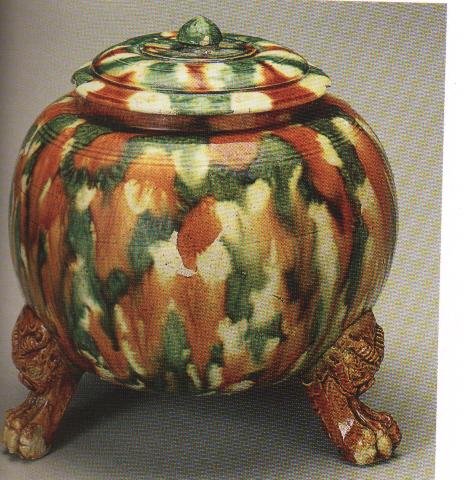

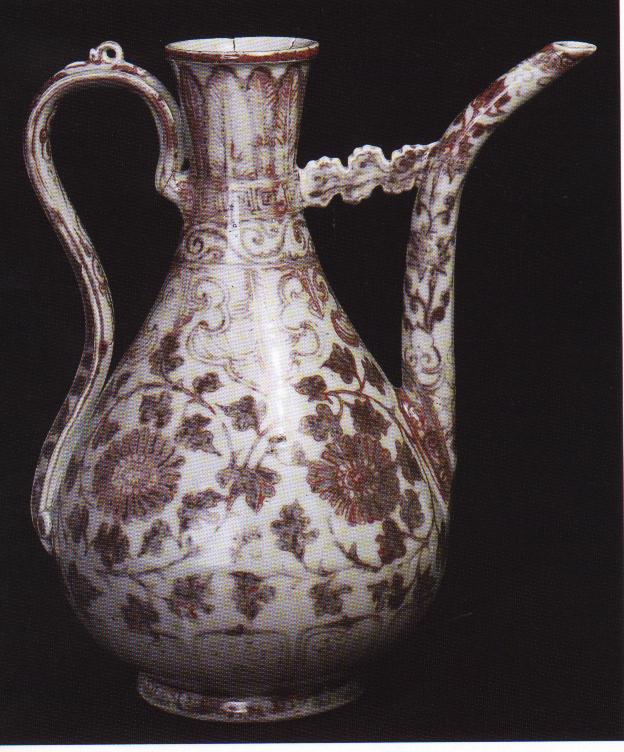

The Tang

dynasty (618-907 A.D.) is arguably the most significant time period in

the evolution of Chinese ceramics because porcelain, the epitome of Chinese

stoneware, was discovered during this dynasty. Even more astounding,

porcelain is not the only development that occurred during the Tang dynasty.

Sancai, also known as “three-colour” wares, were also developed using new

high-lead glazes that produced a plethora of color combinations (Hook 409).

Another addition was marbled pottery, which used different colored clays

to create a swirled look that was painted with a transparent glaze (409).

The final development was expanding the repertoire of shapes of vessels,

many of which were influenced by contacts with the West. During this

time, vases and bowls became quite novel and popular. The interest

in different clay colors used in the marbled pottery helped bring about

the discovery of porcelain, which “evolved out of the conscious attempts

to produce a pure white clay body” (Tharp). The Tang

dynasty (618-907 A.D.) is arguably the most significant time period in

the evolution of Chinese ceramics because porcelain, the epitome of Chinese

stoneware, was discovered during this dynasty. Even more astounding,

porcelain is not the only development that occurred during the Tang dynasty.

Sancai, also known as “three-colour” wares, were also developed using new

high-lead glazes that produced a plethora of color combinations (Hook 409).

Another addition was marbled pottery, which used different colored clays

to create a swirled look that was painted with a transparent glaze (409).

The final development was expanding the repertoire of shapes of vessels,

many of which were influenced by contacts with the West. During this

time, vases and bowls became quite novel and popular. The interest

in different clay colors used in the marbled pottery helped bring about

the discovery of porcelain, which “evolved out of the conscious attempts

to produce a pure white clay body” (Tharp).

There are three major types of Tang porcelain designated by the region

in which the producing kilns were located. The first type is early

whiteware created in Gongxian in the northern part of the Henan province.

Gongxian porcelains had good translucency, and their glazes had good resistance

to dullness and crazing (Wood 97). The porcelains made in Gongxian

included plain whitewares as well as blue and whites, which are porcelains

with a cobalt blue underglaze. Xing porcelain is the most famous

Tang porcelain because it was the whitest produced in the north.

A combination of extremely pure clay and high firing temperatures, as high

as white-blue heat or 1350°C, was needed to produce such white porcelain

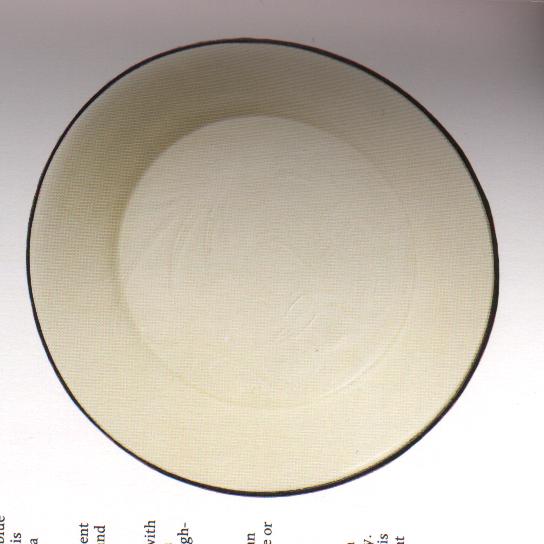

(99). The final type of Tang porcelain is known as Ding ware.

During the Tang, Ding ware was considered inferior to the Xing because

of its creamy color. This opinion of Ding inferiority changed during

the Song dynasty.

There are three major types of Tang porcelain designated by the region

in which the producing kilns were located. The first type is early

whiteware created in Gongxian in the northern part of the Henan province.

Gongxian porcelains had good translucency, and their glazes had good resistance

to dullness and crazing (Wood 97). The porcelains made in Gongxian

included plain whitewares as well as blue and whites, which are porcelains

with a cobalt blue underglaze. Xing porcelain is the most famous

Tang porcelain because it was the whitest produced in the north.

A combination of extremely pure clay and high firing temperatures, as high

as white-blue heat or 1350°C, was needed to produce such white porcelain

(99). The final type of Tang porcelain is known as Ding ware.

During the Tang, Ding ware was considered inferior to the Xing because

of its creamy color. This opinion of Ding inferiority changed during

the Song dynasty.

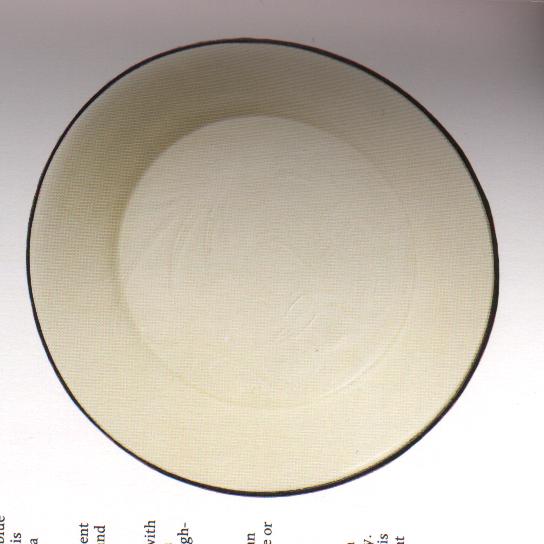

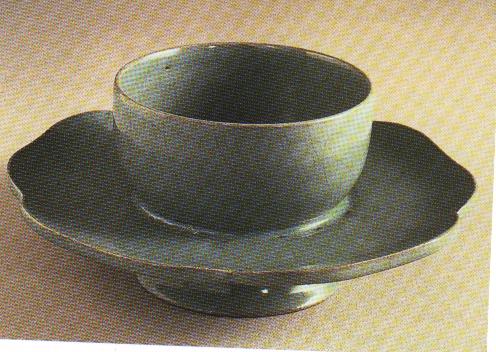

The artisans of the Song dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) perfected what those in

the Tang had begun. The hallmark of Song ceramics is monochrome porcelain

with exquisite form. Ding ware, formally considered second rate,

developed into “plain and beautiful cream-coloured, oxidised porcelain

with austere and refined forms that showed a superb balance of inner and

outer space” (100-1). Decorations changed significantly from the

vibrant colors used in the Tang to the more subdued monochrome glazes and

incised designs. The evolution of Ding ware came to a point when

it was declared the “official palace ware of

The artisans of the Song dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) perfected what those in

the Tang had begun. The hallmark of Song ceramics is monochrome porcelain

with exquisite form. Ding ware, formally considered second rate,

developed into “plain and beautiful cream-coloured, oxidised porcelain

with austere and refined forms that showed a superb balance of inner and

outer space” (100-1). Decorations changed significantly from the

vibrant colors used in the Tang to the more subdued monochrome glazes and

incised designs. The evolution of Ding ware came to a point when

it was declared the “official palace ware of the Northern Song emperors” (Hook 411). Unfortunately, the notoriety

of Ding ware did not last very long for the royal family and was replaced

with Ru ware, “a fine, undecorated ware with a pale grey-green glaze usually

with a faint crackle” (411). The Song had managed to perfect the

creation of vessels to the point where “most of the pots are fully glazed

(including foot and base), because in the kiln the vessels were placed

on tiny supports called spurs that left only minute “sesame-seed” marks

on the glaze” (“Northern Song”). It is said that the Song dynasty

was the time of perfection for Chinese ceramics, and that nothing could

ever compare with it again.

the Northern Song emperors” (Hook 411). Unfortunately, the notoriety

of Ding ware did not last very long for the royal family and was replaced

with Ru ware, “a fine, undecorated ware with a pale grey-green glaze usually

with a faint crackle” (411). The Song had managed to perfect the

creation of vessels to the point where “most of the pots are fully glazed

(including foot and base), because in the kiln the vessels were placed

on tiny supports called spurs that left only minute “sesame-seed” marks

on the glaze” (“Northern Song”). It is said that the Song dynasty

was the time of perfection for Chinese ceramics, and that nothing could

ever compare with it again.

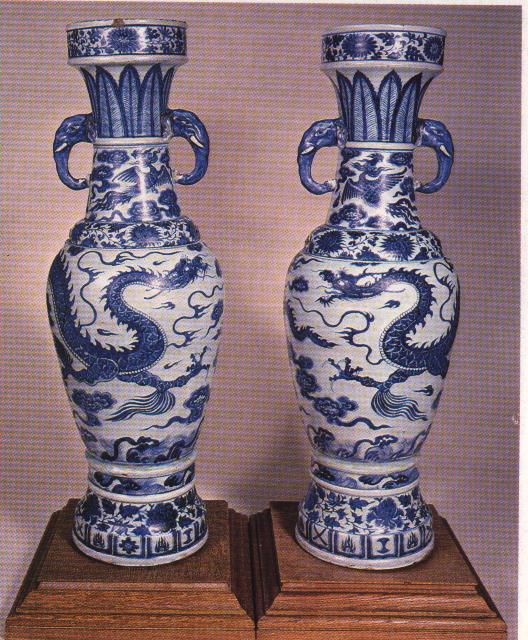

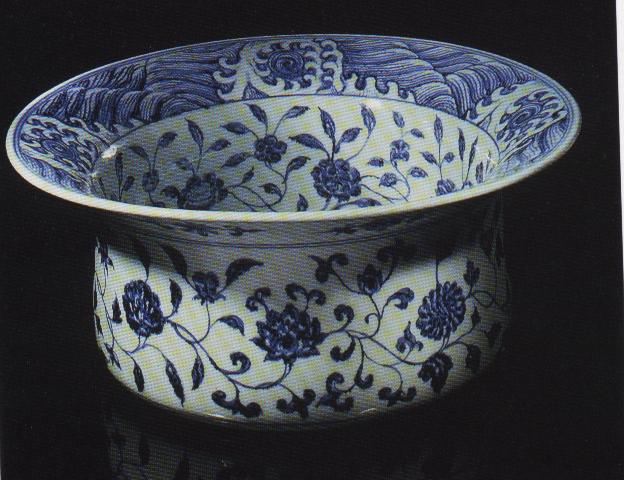

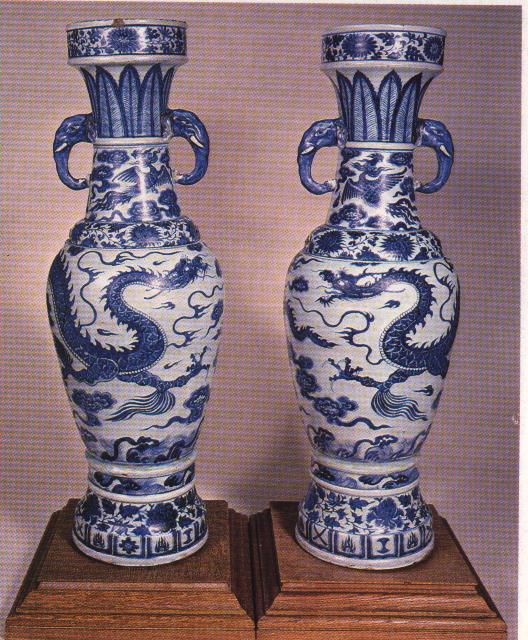

The Yuan

dynasty (1260-1368 A.D.) unfortunately did not keep up to the standards

set by the Song. Although the forms of Yuan and Song pottery are

similar, the excellence in balanced form of the Song was not to be met

by the Yuan. Wares became “heavier and cruder, with new shapes such

as large dishes and bowls” (Hook 413). Even though Yuan wares are

disappointing in aspects such as style and form, decoration is the Yuan’s

saving grace. Images became much more dramatic, naturalistic, and

dynamic. Glazes became less pure, but underglazing with qingbai,

a “thicker and more opaque glaze,” brought about the unquestionably Chinese

blue and white porcelain (413). The Yuan

dynasty (1260-1368 A.D.) unfortunately did not keep up to the standards

set by the Song. Although the forms of Yuan and Song pottery are

similar, the excellence in balanced form of the Song was not to be met

by the Yuan. Wares became “heavier and cruder, with new shapes such

as large dishes and bowls” (Hook 413). Even though Yuan wares are

disappointing in aspects such as style and form, decoration is the Yuan’s

saving grace. Images became much more dramatic, naturalistic, and

dynamic. Glazes became less pure, but underglazing with qingbai,

a “thicker and more opaque glaze,” brought about the unquestionably Chinese

blue and white porcelain (413).

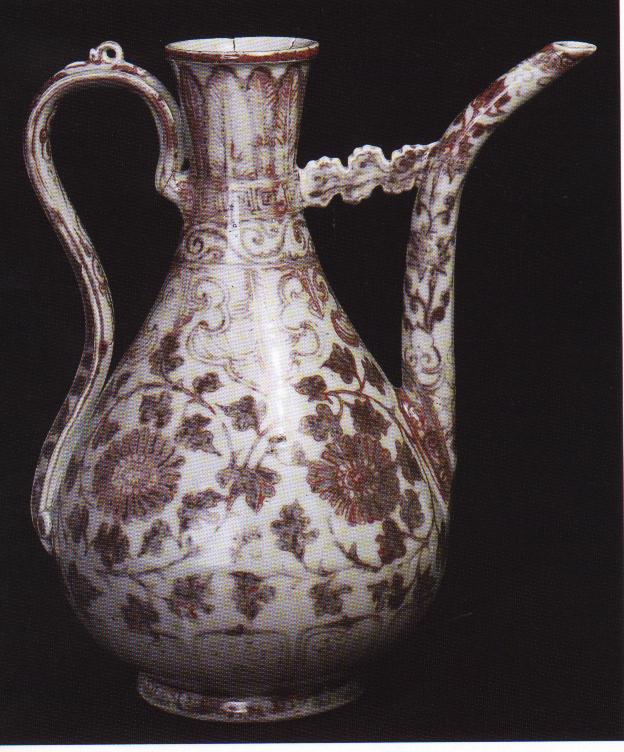

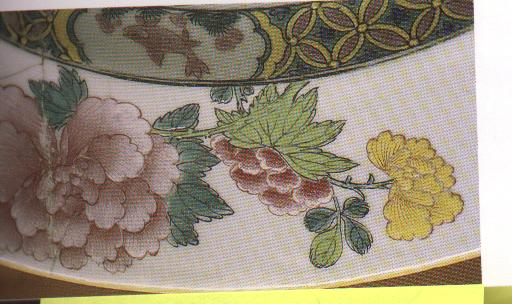

Although the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 A.D.) is best known for its blue

and white porcelain, many types of unique ceramics were developed at this time. The kilns that produced the best quality

and quantity of wares were concentrated at Jingdezhen in the Jiangzi province

because of the deposits of kaolin and petuntse, the most important elements

for porcelain making (416). The kaolin is the key to making very

thin vessels because when heated to high temperatures, upwards of 1,300-1,500°C,

the kaolin becomes extremely hard and strong without too much clay so the

vessels could be made to be almost translucent (Morton 129). These

kilns produced blue and white porcelain along with “red monochromes, and

‘bodiless’

were developed at this time. The kilns that produced the best quality

and quantity of wares were concentrated at Jingdezhen in the Jiangzi province

because of the deposits of kaolin and petuntse, the most important elements

for porcelain making (416). The kaolin is the key to making very

thin vessels because when heated to high temperatures, upwards of 1,300-1,500°C,

the kaolin becomes extremely hard and strong without too much clay so the

vessels could be made to be almost translucent (Morton 129). These

kilns produced blue and white porcelain along with “red monochromes, and

‘bodiless’  imperial wares…[with] anhua, incised in the body under the glaze, visible

only when held up to the light” (Hook 416). Another type of ware

produced at the imperial kilns was doucai, porcelain vessels enameled with

many colors. The effect of doucai is a “true polychrome effect, combining

red, yellow, green, brown, and aubergine overglaze enamels with underglaze

blue” (Wood 233). The popularity of Ming wares could not be stopped,

and large-scale production continued into the Qing dynasty.

imperial wares…[with] anhua, incised in the body under the glaze, visible

only when held up to the light” (Hook 416). Another type of ware

produced at the imperial kilns was doucai, porcelain vessels enameled with

many colors. The effect of doucai is a “true polychrome effect, combining

red, yellow, green, brown, and aubergine overglaze enamels with underglaze

blue” (Wood 233). The popularity of Ming wares could not be stopped,

and large-scale production continued into the Qing dynasty.

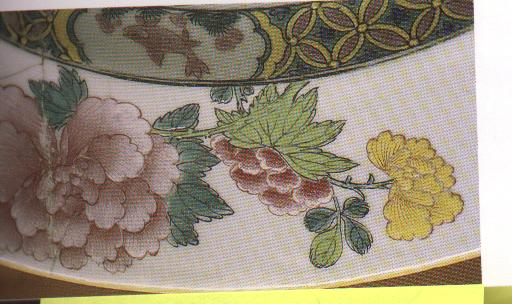

The hallmark of the wares of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 A.D.) was production

over aesthetics or form. Eventually the imperial kilns exchanged

the blue and white wares for the polychrome enamelwares. Two main

types of enamelwares were  produced. The first was famille noire. These wares have a characteristic

blackish-green background. The second type is known as famille rose,

which usually have a white background and the decorations consist of flowers

or birds in yellows and pinks.

produced. The first was famille noire. These wares have a characteristic

blackish-green background. The second type is known as famille rose,

which usually have a white background and the decorations consist of flowers

or birds in yellows and pinks.  Although the Qing developed extraordinary kilns and production systems,

the secret of porcelain making reached Europe and export immediately decreased.

The need to produce large amounts of porcelain was essentially eliminated.

Although the Qing developed extraordinary kilns and production systems,

the secret of porcelain making reached Europe and export immediately decreased.

The need to produce large amounts of porcelain was essentially eliminated.

This paper represents over 7,000 years of ceramic history from the Yangshao’s

simple burnished vessels to the Qing’s technical perfection of production

of porcelain. Although each dynasty certainly has its own unique

features, every style is undeniably Chinese. Aesthetics and function

meld together seamlessly in every object to allow for pleasing yet useful

objects that continue to astound people around the world.

|

Most

often when thinking about Asian ceramics, fine porcelain commonly known

in the West as “china” comes to mind. Where did porcelain come from?

How did the Chinese manage to perfect its manufacturing so many hundreds

of years before the West? These questions can be answered by realizing

that porcelain is only one of many types of ceramics that the Chinese developed

throughout their history. In fact, porcelain came quite late in China’s

history, but its effect on the West is what makes it special. Ceramics

in China can be traced back to the earliest known culture, the Yangshao.

Every culture or dynasty that followed the Yangshao had its own unique

earthenware or stoneware that helped define that particular time period.

This paper will examine the evolution of Chinese ceramics, in both their

components and glazes, beginning with the Yangshao culture thru the Qing

dynasty in order to better understand how the Chinese became so proficient

in making the finest ceramics in the world.

Most

often when thinking about Asian ceramics, fine porcelain commonly known

in the West as “china” comes to mind. Where did porcelain come from?

How did the Chinese manage to perfect its manufacturing so many hundreds

of years before the West? These questions can be answered by realizing

that porcelain is only one of many types of ceramics that the Chinese developed

throughout their history. In fact, porcelain came quite late in China’s

history, but its effect on the West is what makes it special. Ceramics

in China can be traced back to the earliest known culture, the Yangshao.

Every culture or dynasty that followed the Yangshao had its own unique

earthenware or stoneware that helped define that particular time period.

This paper will examine the evolution of Chinese ceramics, in both their

components and glazes, beginning with the Yangshao culture thru the Qing

dynasty in order to better understand how the Chinese became so proficient

in making the finest ceramics in the world.

Chinese

ceramics began with the people of the Yangshao culture in about the year

5000 B.C. near the Wei River. Two major types of pottery were made

at this time. The first was gray everyday earthenware that often

was minimally decorated with “cord, mat, or basket impressions” (Blunden

53). The second type of pottery is more intricate as well as beautiful.

These earthenware pots have a “lightly burnished surface decorated with

painted designs in black, red, maroon, and brown” (53). The decorations

are generally simple geometric patterns such as swirls, but they can be

more ornate and include stylized fish, birds, and human faces (Gernet 39).

As the culture spread westward, the pottery “from the Kansu sites…displays

more elaborate designs” (39). This type of highly decorated pottery

seems to have been used primarily for funerary practices.

Chinese

ceramics began with the people of the Yangshao culture in about the year

5000 B.C. near the Wei River. Two major types of pottery were made

at this time. The first was gray everyday earthenware that often

was minimally decorated with “cord, mat, or basket impressions” (Blunden

53). The second type of pottery is more intricate as well as beautiful.

These earthenware pots have a “lightly burnished surface decorated with

painted designs in black, red, maroon, and brown” (53). The decorations

are generally simple geometric patterns such as swirls, but they can be

more ornate and include stylized fish, birds, and human faces (Gernet 39).

As the culture spread westward, the pottery “from the Kansu sites…displays

more elaborate designs” (39). This type of highly decorated pottery

seems to have been used primarily for funerary practices.

Types of pottery are the central division among Chinese Neolithic cultures.

The Yangshao, as described above, had two main types, with the burnished,

highly decorated pottery being the hallmark style. Following the

Yangshao is the Longshan culture, beginning in approximately 4500 B.C.

and overlapping with the Yangshao for 1500 years. The Longshan were

generally farther east compared to the Yangshao, but some excavation sites

have the Longshan directly succeeding the Yangshao. Like their predecessors,

the Longshan had two types of pottery, but only one is studied with great

care. The Longshan share the more functional gray wares with their

predecessors. The key difference between the cultures is the Longshan

blackware. There are some immediate differences from the highly decorated

Yangshao pieces. First, the Longshan wares are significantly thinner

due to the fact that the vessels were thrown on a potter’s wheel rather

than built by hand. This may have been a consequence of being farther

east and having more contact with the Koreans. Second, Longshan pottery

is has no decoration. These blackwares were made by firing the iron

poor clays initially and then exposing them to smoke. The smoke could

be “penetrated deep into the hot porous ceramics, turning them a fine black

colour- a process known as carbonizing. If the ceramics had been

burnished before firing the result was a deep and glossy black” (Wood 14).

Another major difference in the Longshan pottery is its form, which is

“angular in outline and extremely elegant…Some shapes are already close

to those vessels of the Bronze Age”(Gernet 39). Although the Longshan

culture ends around 2500 B.C., there are no new defining styles of pottery

until the Shang dynasty of 1766 B.C.

Types of pottery are the central division among Chinese Neolithic cultures.

The Yangshao, as described above, had two main types, with the burnished,

highly decorated pottery being the hallmark style. Following the

Yangshao is the Longshan culture, beginning in approximately 4500 B.C.

and overlapping with the Yangshao for 1500 years. The Longshan were

generally farther east compared to the Yangshao, but some excavation sites

have the Longshan directly succeeding the Yangshao. Like their predecessors,

the Longshan had two types of pottery, but only one is studied with great

care. The Longshan share the more functional gray wares with their

predecessors. The key difference between the cultures is the Longshan

blackware. There are some immediate differences from the highly decorated

Yangshao pieces. First, the Longshan wares are significantly thinner

due to the fact that the vessels were thrown on a potter’s wheel rather

than built by hand. This may have been a consequence of being farther

east and having more contact with the Koreans. Second, Longshan pottery

is has no decoration. These blackwares were made by firing the iron

poor clays initially and then exposing them to smoke. The smoke could

be “penetrated deep into the hot porous ceramics, turning them a fine black

colour- a process known as carbonizing. If the ceramics had been

burnished before firing the result was a deep and glossy black” (Wood 14).

Another major difference in the Longshan pottery is its form, which is

“angular in outline and extremely elegant…Some shapes are already close

to those vessels of the Bronze Age”(Gernet 39). Although the Longshan

culture ends around 2500 B.C., there are no new defining styles of pottery

until the Shang dynasty of 1766 B.C.

Very

much like the Shang dynasty, the Zhou dynasty (1027-221 B.C.) did not put

great emphasis on their ceramics. Once again the simple, coarse gray

wares were the main type of pottery produced. The Zhou dynasty did

craft some unique wares including glazed stoneware that was decorated by

both painting and dipping. The wares of the Eastern Zhou (771-221

B.C.) tend to follow the fads of the bronzes because they were an inexpensive

alternative to the bronze vessels used in rituals. These “bargain”

funeral wares of the Warring States period were often made from “fine siliceous

stoneware clays with yellowish, greeny-gray, or dark brown glazes” (Wood

20). The end of the Zhou dynasty marked an important change in China’s

history because the dynasty to follow was the first to unite all of China,

so technically the first truly “Chinese” ceramics were produced during

the Qin.

Very

much like the Shang dynasty, the Zhou dynasty (1027-221 B.C.) did not put

great emphasis on their ceramics. Once again the simple, coarse gray

wares were the main type of pottery produced. The Zhou dynasty did

craft some unique wares including glazed stoneware that was decorated by

both painting and dipping. The wares of the Eastern Zhou (771-221

B.C.) tend to follow the fads of the bronzes because they were an inexpensive

alternative to the bronze vessels used in rituals. These “bargain”

funeral wares of the Warring States period were often made from “fine siliceous

stoneware clays with yellowish, greeny-gray, or dark brown glazes” (Wood

20). The end of the Zhou dynasty marked an important change in China’s

history because the dynasty to follow was the first to unite all of China,

so technically the first truly “Chinese” ceramics were produced during

the Qin.

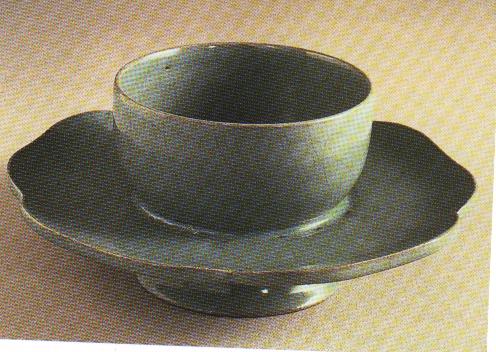

The Tang

dynasty (618-907 A.D.) is arguably the most significant time period in

the evolution of Chinese ceramics because porcelain, the epitome of Chinese

stoneware, was discovered during this dynasty. Even more astounding,

porcelain is not the only development that occurred during the Tang dynasty.

Sancai, also known as “three-colour” wares, were also developed using new

high-lead glazes that produced a plethora of color combinations (Hook 409).

Another addition was marbled pottery, which used different colored clays

to create a swirled look that was painted with a transparent glaze (409).

The final development was expanding the repertoire of shapes of vessels,

many of which were influenced by contacts with the West. During this

time, vases and bowls became quite novel and popular. The interest

in different clay colors used in the marbled pottery helped bring about

the discovery of porcelain, which “evolved out of the conscious attempts

to produce a pure white clay body” (Tharp).

The Tang

dynasty (618-907 A.D.) is arguably the most significant time period in

the evolution of Chinese ceramics because porcelain, the epitome of Chinese

stoneware, was discovered during this dynasty. Even more astounding,

porcelain is not the only development that occurred during the Tang dynasty.

Sancai, also known as “three-colour” wares, were also developed using new

high-lead glazes that produced a plethora of color combinations (Hook 409).

Another addition was marbled pottery, which used different colored clays

to create a swirled look that was painted with a transparent glaze (409).

The final development was expanding the repertoire of shapes of vessels,

many of which were influenced by contacts with the West. During this

time, vases and bowls became quite novel and popular. The interest

in different clay colors used in the marbled pottery helped bring about

the discovery of porcelain, which “evolved out of the conscious attempts

to produce a pure white clay body” (Tharp).

There are three major types of Tang porcelain designated by the region

in which the producing kilns were located. The first type is early

whiteware created in Gongxian in the northern part of the Henan province.

Gongxian porcelains had good translucency, and their glazes had good resistance

to dullness and crazing (Wood 97). The porcelains made in Gongxian

included plain whitewares as well as blue and whites, which are porcelains

with a cobalt blue underglaze. Xing porcelain is the most famous

Tang porcelain because it was the whitest produced in the north.

A combination of extremely pure clay and high firing temperatures, as high

as white-blue heat or 1350°C, was needed to produce such white porcelain

(99). The final type of Tang porcelain is known as Ding ware.

During the Tang, Ding ware was considered inferior to the Xing because

of its creamy color. This opinion of Ding inferiority changed during

the Song dynasty.

There are three major types of Tang porcelain designated by the region

in which the producing kilns were located. The first type is early

whiteware created in Gongxian in the northern part of the Henan province.

Gongxian porcelains had good translucency, and their glazes had good resistance

to dullness and crazing (Wood 97). The porcelains made in Gongxian

included plain whitewares as well as blue and whites, which are porcelains

with a cobalt blue underglaze. Xing porcelain is the most famous

Tang porcelain because it was the whitest produced in the north.

A combination of extremely pure clay and high firing temperatures, as high

as white-blue heat or 1350°C, was needed to produce such white porcelain

(99). The final type of Tang porcelain is known as Ding ware.

During the Tang, Ding ware was considered inferior to the Xing because

of its creamy color. This opinion of Ding inferiority changed during

the Song dynasty.

The artisans of the Song dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) perfected what those in

the Tang had begun. The hallmark of Song ceramics is monochrome porcelain

with exquisite form. Ding ware, formally considered second rate,

developed into “plain and beautiful cream-coloured, oxidised porcelain

with austere and refined forms that showed a superb balance of inner and

outer space” (100-1). Decorations changed significantly from the

vibrant colors used in the Tang to the more subdued monochrome glazes and

incised designs. The evolution of Ding ware came to a point when

it was declared the “official palace ware of

The artisans of the Song dynasty (960-1279 A.D.) perfected what those in

the Tang had begun. The hallmark of Song ceramics is monochrome porcelain

with exquisite form. Ding ware, formally considered second rate,

developed into “plain and beautiful cream-coloured, oxidised porcelain

with austere and refined forms that showed a superb balance of inner and

outer space” (100-1). Decorations changed significantly from the

vibrant colors used in the Tang to the more subdued monochrome glazes and

incised designs. The evolution of Ding ware came to a point when

it was declared the “official palace ware of the Northern Song emperors” (Hook 411). Unfortunately, the notoriety

of Ding ware did not last very long for the royal family and was replaced

with Ru ware, “a fine, undecorated ware with a pale grey-green glaze usually

with a faint crackle” (411). The Song had managed to perfect the

creation of vessels to the point where “most of the pots are fully glazed

(including foot and base), because in the kiln the vessels were placed

on tiny supports called spurs that left only minute “sesame-seed” marks

on the glaze” (“Northern Song”). It is said that the Song dynasty

was the time of perfection for Chinese ceramics, and that nothing could

ever compare with it again.

the Northern Song emperors” (Hook 411). Unfortunately, the notoriety

of Ding ware did not last very long for the royal family and was replaced

with Ru ware, “a fine, undecorated ware with a pale grey-green glaze usually

with a faint crackle” (411). The Song had managed to perfect the

creation of vessels to the point where “most of the pots are fully glazed

(including foot and base), because in the kiln the vessels were placed

on tiny supports called spurs that left only minute “sesame-seed” marks

on the glaze” (“Northern Song”). It is said that the Song dynasty

was the time of perfection for Chinese ceramics, and that nothing could

ever compare with it again.

The Yuan

dynasty (1260-1368 A.D.) unfortunately did not keep up to the standards

set by the Song. Although the forms of Yuan and Song pottery are

similar, the excellence in balanced form of the Song was not to be met

by the Yuan. Wares became “heavier and cruder, with new shapes such

as large dishes and bowls” (Hook 413). Even though Yuan wares are

disappointing in aspects such as style and form, decoration is the Yuan’s

saving grace. Images became much more dramatic, naturalistic, and

dynamic. Glazes became less pure, but underglazing with qingbai,

a “thicker and more opaque glaze,” brought about the unquestionably Chinese

blue and white porcelain (413).

The Yuan

dynasty (1260-1368 A.D.) unfortunately did not keep up to the standards

set by the Song. Although the forms of Yuan and Song pottery are

similar, the excellence in balanced form of the Song was not to be met

by the Yuan. Wares became “heavier and cruder, with new shapes such

as large dishes and bowls” (Hook 413). Even though Yuan wares are

disappointing in aspects such as style and form, decoration is the Yuan’s

saving grace. Images became much more dramatic, naturalistic, and

dynamic. Glazes became less pure, but underglazing with qingbai,

a “thicker and more opaque glaze,” brought about the unquestionably Chinese

blue and white porcelain (413).

were developed at this time. The kilns that produced the best quality

and quantity of wares were concentrated at Jingdezhen in the Jiangzi province

because of the deposits of kaolin and petuntse, the most important elements

for porcelain making (416). The kaolin is the key to making very

thin vessels because when heated to high temperatures, upwards of 1,300-1,500°C,

the kaolin becomes extremely hard and strong without too much clay so the

vessels could be made to be almost translucent (Morton 129). These

kilns produced blue and white porcelain along with “red monochromes, and

‘bodiless’

were developed at this time. The kilns that produced the best quality

and quantity of wares were concentrated at Jingdezhen in the Jiangzi province

because of the deposits of kaolin and petuntse, the most important elements

for porcelain making (416). The kaolin is the key to making very

thin vessels because when heated to high temperatures, upwards of 1,300-1,500°C,

the kaolin becomes extremely hard and strong without too much clay so the

vessels could be made to be almost translucent (Morton 129). These

kilns produced blue and white porcelain along with “red monochromes, and

‘bodiless’  imperial wares…[with] anhua, incised in the body under the glaze, visible

only when held up to the light” (Hook 416). Another type of ware

produced at the imperial kilns was doucai, porcelain vessels enameled with

many colors. The effect of doucai is a “true polychrome effect, combining

red, yellow, green, brown, and aubergine overglaze enamels with underglaze

blue” (Wood 233). The popularity of Ming wares could not be stopped,

and large-scale production continued into the Qing dynasty.

imperial wares…[with] anhua, incised in the body under the glaze, visible

only when held up to the light” (Hook 416). Another type of ware

produced at the imperial kilns was doucai, porcelain vessels enameled with

many colors. The effect of doucai is a “true polychrome effect, combining

red, yellow, green, brown, and aubergine overglaze enamels with underglaze

blue” (Wood 233). The popularity of Ming wares could not be stopped,

and large-scale production continued into the Qing dynasty.

produced. The first was famille noire. These wares have a characteristic

blackish-green background. The second type is known as famille rose,

which usually have a white background and the decorations consist of flowers

or birds in yellows and pinks.

produced. The first was famille noire. These wares have a characteristic

blackish-green background. The second type is known as famille rose,

which usually have a white background and the decorations consist of flowers

or birds in yellows and pinks.  Although the Qing developed extraordinary kilns and production systems,

the secret of porcelain making reached Europe and export immediately decreased.

The need to produce large amounts of porcelain was essentially eliminated.

Although the Qing developed extraordinary kilns and production systems,

the secret of porcelain making reached Europe and export immediately decreased.

The need to produce large amounts of porcelain was essentially eliminated.