|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Akira Kurosawa was one of the most famous Japanese filmmakers

in the world. He was born to a military family where morals and a

good code of behavior were necessary. He had a very good sense for

the bushido code and it was manifested in his art. They were what

he lived by and what often propelled his films. The bushido codes

could be used for multiple allegorical layers. These layers consisted

of “the nonexistence anywhere of any absolute truth,” “to know and

to act are one and the same,” and creating something that is completely

Japanese and that also focuses on the people. Furthermore, historical

significance can be attributed to three of his films in different and similar

ways. The three films to be analyzed are Rashomon, The Seven Samurai

and Yojimbo.

It is first essential to understand a little bit about Kurosawa before delving into the significant affect his films had on the Japanese people. He was born on March 23, 1910, in Tokyo. He projected the true form of Japanese tradition in its purest form. He was a moralist and believed in integrity of action. His characteristics are those that are very similar to the bushido codes samurai abided by. Kurosawa is fundamentally different from other directors because he based his films on ideas rather than focusing on the unraveling of the story. Common themes often comprised of courage, compassion and the nature of reality.

Kurosawa made three films that have pertinent significance in the development of a Japanese identity, Rashomon, The Seven Samurai, and Yojimbo. Rashomon has always been Kurosawa’smost recognizable film in the world film circuit. The allegorical story of this film is the uncertainty and impossibility of attaining truth. It has been described by David Desser that Rashomon is almost like a detective story, but the importance is not who did the crime, but how. Asking how allows the multi-leveled essence of truth in the film.

There was a release of existing morals through Rashomon. It engaged people to think in a different way. There is the conflict of stories in the film, which represents the fact that the variation is due to the effort of the characters to vindicate themselves by improving the circumstances that they could control. It skews from the traditional view of loyalty, honor and pride. The absence of truth disillusions the self-portrait of the characters. This has direct correlation with the war years in Japan. They were under the notion that they were technologically behind the rest of the world, which gave them an inferiority complex. The imperialistic effort was a manifestation of their complex; they were disillusioned to believe that the responsibility of Asia lay in their hands and that they had the obligation to liberate it from western authority. So, in a sense, where fabrication of the truth leads to self-disillusion, fabrication of Samurai pride gave Japan the disillusionment that they had to liberate Asia.

The issue of truth is very nihilistic in nature. The writer of the original story was obsessed with the mistrust of humanity and ended up killing himself due to despair. It is apparent throughout the film, when the four stories are told and they all seem believable. It is known that only one can ultimately be true, but which one to believe is the mystery. It is a mystery that will be left unsolved. Initially, it was surprising to see such a nihilistic nature prevalent in a Kurosawa film; it contradicts his humanistic beliefs and at the same time compliments his life long problem of not understanding why people cannot live happier together. Perhaps the nonexistence of truth contributes to this. Yet, in the end we see Kurosawa leave his humanistic strength as the resonating affect when the woodcutter adopts the abandon baby as his own.

Kurosawa

was a master at portraying traditional Japanese beliefs and adapting it

to the understanding of other people. Although he claims that his

films are for him and whether or not other people find significance in

it is chance; he does have the ability to connect with people through his

films. Before merging into the other two films it is important to

understand the composition of samurai films and bushido codes, as they

play a large role in Kurosawa’s interpretation.

Kurosawa

was a master at portraying traditional Japanese beliefs and adapting it

to the understanding of other people. Although he claims that his

films are for him and whether or not other people find significance in

it is chance; he does have the ability to connect with people through his

films. Before merging into the other two films it is important to

understand the composition of samurai films and bushido codes, as they

play a large role in Kurosawa’s interpretation.

The lives of Samurai changed when the Tokugawa Period brought peace. They were no longer needed and they grew lazy, so they became the new administrative staff in the government. The new frontier the samurai had to worry about is its near extinction. By World War II samurai are completely expunged. Their bushido codes would be left to be forgotten by society and the young never made aware of what it truly means. SCAP even had regulations on films when they came in for occupation, and it made samurai films impossible to be made due to its frowning upon feudal loyalty and seppuku. After their defeat in World War II, the Japanese people were no longer interested in bushido, but more with democracy. But the bushido codes are what influenced Kurosawa’s life and films.

Philosophically, bushido stressed many maxims regarding life. Such maxims include that fact that no matter how perfect something may seem, nothing can indeed be perfect. It is an impossibility. Bushido also stresses that it has no goals and there is no chance of ever being complete. There is always a process, and in life it is living. Nobody can be a complete being or something accomplished, an end product. Therefore the focus is on a way of living through action. The films often portray a hero that understands that it is difficult to know. The villains are the ones who think they know, but in the end fail because they are unaware of bushido codes. People talk about bushido being present in Kurosawa himself; he is considered “the last of the samurai.” Kurosawa was so significant because he resurrected the bushido in Japan just when it was needed. People were forgetting their heritage and because of Kurosawa it has been revived.

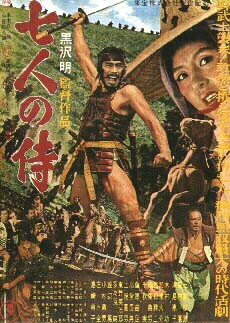

It was said that the “ambition and complexity of The Seven Samurai go far beyond the dramatic framework of the Western,” in the United States. Although the content was never the top priority in Kurosawa’s films, often it worked very well with what he was doing. Kurosawa had the ability to make scene of great happiness and then contrast it with a “blood-freezingly sad scene.” Many critics consider the Seven Samurai the best epic film in Japan. The film was the first of what is considered a nostalgic samurai drama. These films gave the audience a feeling of something indescribably nostalgic. It was indescribable due to the fact that Kurosawa revived these bushido ideas right when people were forgetting it, and for the young, they had no experience with bushido codes.

The Seven Samurai took place prior to the peaceful Tokugawa Shogunate. This was a time of civil war and constant upheaval. There was a need for an ethics and morals to lead the way into hope. There was usually a lack of authority, hence leaving the ethical model as the samurai. By having an individual at the center of ethical thought in the film, Kurosawa reversed the traditional Japanese film. The ethics are established through the individuals, not from a preexisting authority.

Yojimbo was a very politically loud film. It was a very typical Kurosawa “one-man-against-town” film. The film’s time period is the end of the Tokugawa Period, when people where beginning to forget about their traditions and attempting to compete with the West. The samurais were being erased. Part of the Westernization included making a transition into a capitalist economy, and Kurosawa uses the Japanese attempt to capitalize in satire. Prior to the effort to Westernize, people in Japan followed the trade of their parents. But in the film, a son wants to leave the family inn to get more money in the town. Furthermore, there is a feud in the town between two families fighting over the silk trade. The film criticizes the economic basis the families are fighting over. They are competing to have a more successful silk trade than the other, which would have never been the basis for clans to war in ancient Japan. Their greed for money results in the demolishment of the entire town. The ronin character helps destroy the corrupt economic policies of the families, yet he makes the effort to reunite a woman with her family. Desser has described the ronin’s purpose is to be destroyer and restorer. The ronin samurai even plays off of the economic competition by constantly forcing the other family to outbid each other to attain his services. He watches them as they deteriorate as human beings into marionettes that are easily controllable through the influence of money. The representation of the town, both in appearance and action of its constituents, is a reversal of what traditional Japan was; and oddly enough, it reflects Kurosawa’s perspective and opinion of what was happening in Japan at the time.

When Sanjuro, the ronin samurai, leaves the town he says that the town will be much more peaceful and quiet now. When he says this there is almost nobody left alive. Perhaps it was a suggestion that Japan had better abandon the extreme attention given to Westernization and try to revive their own traditions.

While Yojimbo was a political satire on the societal concern of economics at the time, The Seven Samurai was a glorious resurrection of bushido Japan and Rashomon certainly reflected the disillusionment of life and helped explain how Japan may have been disillusioned. He provided opinion, positive bushido ethics and moral support for a shattered post-World War II nation. No matter what else Kurosawa did, he certainly revived the bushido spirited heritage in Japan: “and it was this spirit which led to the recovery of Japan after the war.”

Andre Bazin, “Seven Samurai.” Perspectives on Kurosawa. ed. James Goodwin, New York: G.K. Hall & Co., 1994.

David Desser. The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1981.

Patricia Erens. Akira Kurosawa: A guide to references and resources. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1979.

Akira Iwasaki. “Kurosawa and His Work.” Great Film Directors. ed. Leo Braudy and Morris Dickstein. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 557.

Donald Richie. “Kurosawa’s Style.” Great Film Directors, 552.

Tadao Sato, “Akira Kurosawa: Tradition in a Time of ransition,”<www.usc.edu/isd/archives/asianfilm/japan/kuro-trad.html>, 2 April 2002.

http://home.earthlink.net/~ronintom/Kurosawa.htm

http://home.earthlink.net/~ronintom/Kurosawa.htm

Site Created by: Michael V. Comerford III