|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After World War II, Japan accepted an article in its constitution that

stated that it was against the use of any force to resolve an international

dispute and that it would not recognize the belligerency of the state.

That meant that Japan would not create any sort of military force to be

used as a potential for war. However, situations in the world soon changed

and Japan was forced to take another look at this article and determined

that it could create a standing self defense force and it would not be

unconstitutional. This self defense force is now one of the best equipped

military force in the world, trailing only the United States and Russia

in military spending. Is Japan getting ready to once again draw its proverbial

sword as a means to protect its own interests? This apparently seems to

be the situation in East Asia, with China slowly becoming the economic

leader in the region.

After the Second World War, while America was occupying Japan, General Douglas MacArthur demanded that the Japanese come up with a new, more liberal constitution that would satisfy the West. By placing the power into the people, and relegating the Emperor to just a figurehead, MacArthur believed that the threat of a resurgence in Japanese aggression would not happen. After many attempts that did not satisfy MacArthur, he ordered his subordinates to draft a constitution themselves, in less than a week.

The document that these young officials created still remains intact as the Constitution of Japan with only minor revisions (American Experience, 1). The most unique part about this constitution is Article 9, which states:

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.This Article has been key to the Japanese governmentís continued refusal to rearm and bow to Americaís pressures during the Cold War, but the irony is that this article has allowed an extremely powerful "self defense force" to be created in Japan, quite possibly the second strongest military in the world.In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

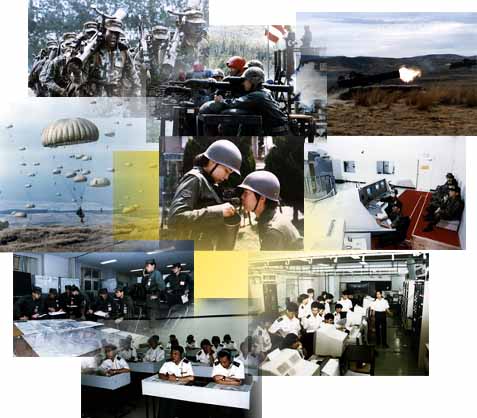

As the Cold War began, American foreign policy went through a radical change. With the spread of Communism threatening Capitalist markets in Asia, America was beginning to have second thoughts about placing Article 9 in the Japanese Constitution. Due to the Korean War, the importance of Japan remaining an ally increased, as the domination of Communism in East Asian countries seemed to become an increasing threat. Japanís role as a platform for Americaís offensive in Asia continued to grow as the Korean War continued (Hayes, 290). To complete this defensive relationship, the United States and Japan signed the Mutual Defense Assistance agreement in which Japan agreed to take Ďall reasonable measures which may be needed to develop its defense capacities. (Harries, 239)í From there, the Self Defense Force (SDF) was created only as a means to defend against Soviet aggression. For the decades after, the SDF has quietly been continuing its position in Japanese society as a purely defensive force. However, this Self Defense Force has become second only to the United States in effective strength, and third in military spending behind America and Russia, and many people are suggesting that the Japanese are now in a state of re-militarization.

It is no secret that for a long time, many Japanese

politicians have wanted to change Article 9 or abolish it entirely.

However, the Japanese people themselves still sway back and forth between

supporting the principles and changing them to fit todayís modern time

(Harries, 275). Throughout the 1970ís, Japan was continually

pressured by the United States to modernize its defensive forces and increase

their military spending. In 1976, the SDF began its rapid modernization

to replace older aircraft and submarines with newer, more powerful versions.

Many Japanese citizens were against this, claiming that Japan was breaking

the rules set forth in Article 9, so to pacify them, the Japanese Diet

set a limit on military spending to 1 percent of their GDP (Hayes, 292).

However, during the hawkish Reagan administration, the United States continued

to pressure the Japanese to increase their military expenditure and they

responded by dropping the 1% cap. Today, Japanese military spending

now is stable around 1 percent, but when you consider that they are only

third in world for total GDP, behind the United States and China, 1 percent

is a very large amount (CIA Factbook, 2001).

In 2001, the total United States GDP was 9.963 trillion dollars, and their military expenditure was 396 billion. To compare, Japanís GDP was 3.15 trillion, with 45.6 billion going to their Self Defense Force. Granted, compared to the United States, this sum seems rather paltry, but it is only 15 billion behind Russia, the second largest military spender in the world (CDI). This seems to go counter against Article 9, and indeed, many groups in Japan have taken the SDF to higher level courts, challenging them on the grounds that they are unconstitutional. However, the courts seem to always favor the SDF, as long as they remain defensive units. As long as the Japanese policy remains defensive, Article 9 will not be seen as a hindrance towards the SDF (Hayes, 300). In 1991, the Gulf War was entering its first stages, and Japan was at the crux of a decision that would turn out to be a very harsh condemnation to the Japanese government by the West.

With the Gulf War in its beginning stages, the United States called on its allies to provide military support for the war against Iraq. Japan debated for weeks in the Diet, trying to decide what decision they should make. In the end, the Japanese spent so long trying to determine what action they should take, the 6 naval minesweepers they sent to the Persian Gulf did not even arrive until after the war had concluded. And although they contributed 13 of the 80 billion dollar cost of the war, their so called checkbook diplomacy backfired on them, when they were criticized and condemned for being willing to send money, but declined to assist the international coalition with military forces (Struck). The Gulf War turned out to be a very bitter decision for the Japanese, and many regret the decision that was made, especially a young diplomat named Junichiro Koizumi.

Elected as the Prime Minister of Japan in 2001, Koizumi was seen as the man who could end the conservative reign of the LDP and would remove the cliques that controlled the Japanese government. While his success in doing this is arguable, he is a strong supporter of the SDF and vowed to expand its influence (Stratfor). With the United States slowly pulling out of the politics in East Asia, the political scene is beginning to shift, where the major players who remain are China and Japan. Already, Japan has a military that is technologically superior to everyone else in Asia, except that they arenít officially a military. Koizumi is calling on the SDF to become a faster, more mobile force that can deal with threats from all over the world. In his first speech to the Diet, he pushed for a more hawkish policy, saying, "We must not allow ourselves to be complacent with peace and become oblivious to the possibility of disturbances." Koizumiís words seem to echo Japanese public sentiment, as a newer generation is coming to power, and wants Japan to play a larger role in the security of Asia (Stratfor).

One thing that will remain forever with Japan is their staunch opposition to the construction of any nuclear weapon whatsoever. While they may be torn either way in regards to the SDF, their stance on nuclear weapons is clear. In December 1967, Prime Minister Eisaku Sato proposed the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. These principles state that Japan shall not possess nuclear weapons, that they will not manufacture nuclear weapons and lastly, that they will not allow the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan (Hayes, 294). Popular culture has produced many versions of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in a very graphic manner, and 350,000 people are still entitled to special medical care for the effects of an atomic bomb. The Japanese have a strong emotional link to the threat of nuclear war and anything that may bring this kind of war closer (Harries, 287).

The events of September 11th, 2001 have caused Japan to re-evaluate its

stance on global operations. Prime Minister Koizumi, determined not

to have the same pitfalls that plagued the Japanese government during the

Persian Gulf War, created a seven point plan that, among other things,

will provide logistical, intelligence and financial aid to the United States.

For the first time since World War II, Japan forces will be deployed outside

of its national borders as a US led war against Osama bin Laden.

While Koizumi has called for the deployment of the SDF, he is wary of overstretching

the bounds of Article 9. In addition, many of its Asian neighbors

are still very wary of any sort of revitalization and assertiveness from

Japan, as they still remember the actions of World War II. Lots of

diplomats are watching the SDFís role, and any boost in its military role

would be sure to cause controversy in Eastern Asia due to Japanís past

militarism and imperialism (Glosserman). Both China and South Korea

have deep concerns over any kind of growth in Japanís military. This

is a test for Japan to not only play a larger part in the global community,

but also to see how far it can stretch Article 9.

The events of September 11th, 2001 have caused Japan to re-evaluate its

stance on global operations. Prime Minister Koizumi, determined not

to have the same pitfalls that plagued the Japanese government during the

Persian Gulf War, created a seven point plan that, among other things,

will provide logistical, intelligence and financial aid to the United States.

For the first time since World War II, Japan forces will be deployed outside

of its national borders as a US led war against Osama bin Laden.

While Koizumi has called for the deployment of the SDF, he is wary of overstretching

the bounds of Article 9. In addition, many of its Asian neighbors

are still very wary of any sort of revitalization and assertiveness from

Japan, as they still remember the actions of World War II. Lots of

diplomats are watching the SDFís role, and any boost in its military role

would be sure to cause controversy in Eastern Asia due to Japanís past

militarism and imperialism (Glosserman). Both China and South Korea

have deep concerns over any kind of growth in Japanís military. This

is a test for Japan to not only play a larger part in the global community,

but also to see how far it can stretch Article 9.

So the question remains, is Japan once again slowly drawing its sword and remilitarizing or is it faithfully trying to observe Article 9? Certainly, Japanís military spending is not one of a pacifistic nature, and it is only a matter of time until it surpasses Russia. Their SDF is already technologically the second most effective military in the world. However, Japan has always resisted any sort of attempt by the United States to rearm themselves and become a larger military player in the global landscape. With the demise of the Soviet Union, Americaís interest in the Pacific Rim has decreased, so it is only a matter of time until Japan and China race for dominance in Eastern Asia. And while the risks of an apocalyptic war between the superpowers have subsided, a regional war in Asia is a very strong possibility. Before September 11th, situations between India and Pakistan were continuing downward in a spiral that seemed to inevitably to war. While this new coalition on terror has changed the global landscape and alliances for the moment, we never know what the future may hold.

On the outside, while Japan is not aggressive, it has the military strength to not have to be concerned with any sort of foreign threat. However, it is able to respond to threats that other countries could pose to it. With Chinaís economic strength growing and Japanís economy seemingly in a downward spiral, soon there may be a shift in power in Eastern Asia. With Americaís declining participation in the Pacific Rim, what Japan fears most is a China that has the economic strength and ability to rapidly rebuild their military. Japanís pacifistic policy may work while they are still the strongest power in East Asia, but if they begin to lag behind China, it would be likely for a policy change to occur regarding Article 9. This situation still is many years away, but on the current economic tracks of both countries, this scenario will no doubt occur (Hayes, 169).

While political leaders still want to increase the role of Japanís military in the world, Japanís populace still has strong ties to their anti-war sentiments. However, the World War II generation is slowly fading away in Japan and younger, more nationalistic citizens start becoming the voice of Japan, these sentiments may become just a relic of the past. Japan is in the position to change its military into a more aggressive outfit, ready to become more like the United Statesí modern military machine. With military spending soon to outpace Russia, and the possibility that Japan may lose its status as the number one economic powerhouse in East Asia, the situation for the military hawks in the government is sure to become more favorable. There will always be the bureaucrats in Japan who want the SDF to take a more active military role in the region, and the voices of the survivors of World War II will eventually decline. Make no mistake, Japan is still a military powerhouse. The only question that remains is whether the military will remain a self defense force, or eventually change into a national military that is willing to impose its influence on Asia. Japan may have their proverbial sword sheathed at the moment, but it seems to be only a matter of time until this sword is drawn once again.

The significance of Japan rearming itself has implications around the world. It would most certainly cause more conflict in the East Asia region, as well as giving Japan the possibility of asserting its will around the world. As we have seen, Japan already has a strong, technologically advanced defensive force which could quickly be changed into something used for offense. With China becoming the region's most powerful economic player, Japan surely will begin to feel more pressure on its economy. As the Chinese become an ever greater threat, Article 9 of Japan's constititution may once again be scrutinized to ensure that the Japanese will remain the strongest player in the East.

Harries, Meirion and Susie. Sheathing the Sword. New York, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. 1987.

Hayes, Louis D. Introduction to Japanese Politics. New York, New York: M.E. Sharpe. 2001

Hayes, Declan. Japan: The Toothless Tiger. Boston, Massachusetts: Tuttle Publishing. 2001.

Works Consulted

Axelbank, Albert. Black Star Over Japan. Hill and Wang. 1972.

Beauchamp, Edward, ed. Dimensions of Contemporary Japan: Japan's Role in International Politics since World War II. New York, New York: Garland Inc. 1998

Hanneman, Mary L. Japan Faces the World: 1925-1952. London, England: Pearson Education Limited. 2001.

The CIA World Factbook 2001: Japan

The CIA World Factbook: United States

Glosserman, Brad. Japan Battles Gulf War Ghosts. 28 Sept 2001.

Stratfor.com. Will Japan Rearm?

Site Created by:

Jim Donahue