During the Meiji period (1868-1912), the influx

of new ideas and technology had a sweeping impact on all areas of Japanese

life. At the same time, Japan still tried to hold onto its own cultural

identity. In the end a synthesis of the old and new would bring about

modern Japan.

Many of the Japanese were quick to adopt western style both in their appearance

and actions. For example, the traditional Japanese hair cut for males

was the chomímage. This called for the head to be shaved except

for the rear, which was then pulled up and folded over the top of the head.

Thanks to its high maintenance and uncomfortable nature, it did not take

long for many men to switch to western hairstyles, especially those men

who were engaged in the new professions like school teacher, policeman,

or Meiji official. However, when the Meiji government finally came

out against the chomímage, some people fervently defended the old style.

There were even reports of mothers rejecting sons who came back from the

city or the army without their chomímage, and bridegrooms finding themselves

suddenly unworthy of their fiancées. (Shibusawa, 38)

Many of the Japanese were quick to adopt western style both in their appearance

and actions. For example, the traditional Japanese hair cut for males

was the chomímage. This called for the head to be shaved except

for the rear, which was then pulled up and folded over the top of the head.

Thanks to its high maintenance and uncomfortable nature, it did not take

long for many men to switch to western hairstyles, especially those men

who were engaged in the new professions like school teacher, policeman,

or Meiji official. However, when the Meiji government finally came

out against the chomímage, some people fervently defended the old style.

There were even reports of mothers rejecting sons who came back from the

city or the army without their chomímage, and bridegrooms finding themselves

suddenly unworthy of their fiancées. (Shibusawa, 38)

As with hairstyles, it was people in

the new professions and the army who took the lead in adopting western

clothes. Even then, in the cities, it was not uncommon to see someone

in a kimono with western shoes or in an obi worn with spectacles and an

umbrella. Traditional clothes remained in place though for those

engaged in traditional roles such as farming or fishing. It took

a longtime for the new ways to penetrate the countryside because there

was little reason to change, and actually, many of the changes in the villages

came from veterans returning from service and the young who had gone to

the city. (Shibusawa, 26)

The science and technology of the West

was quick to find its way into Japanese society. It was Commodore Perry

who demonstrated the telegraph to the imperial court in 1853. Soon

the first line was strung from Yokohama to Tokyo. However, many people

thought that there was black magic at work in the device. One rumor

said that the wires were soaked in the blood of unmarried women. Others

in the country were perplexed when they hung messages written on paper

from the wire and they did not fly down the line. Fear over the new technology

even led to riots in Hiroshima in 1871. It did not gain wide acceptance

right away because of these superstitions and the high cost of transmitting

messages and as such was primarily used by officials and the new newspapers.

(Shibusawa, 252)

Western thought had a tremendous impact on

Japanese culture at this time. With the establishment of the Institution

for Study of Barbarian Literature a steady stream of Western ideas and

entertainments were translated into Japanese. Samuel Smiles' book

Self Help and Lord Lyton's novel Ernest Moltavers became

huge successes in translation. Also several young men were sent to

study abroad in Europe and America under the Bureau of Western Learning.

They came back to Japan with the texts of John Stuart Mill, the Constitution

of the United States, German philosophers such as Hegel and Kant, and the

Social Darwinists for a country ready for new ideas. Ideas of economic

liberalism, the need for a market economy, and equality under the law resonated

with many in Japan's new generation. Fukuzawa Yukishi, the prolific

writer and great champion of westernization, said, "To abstain from intercourse

with foreign nations was a contradiction of both the laws of nature and

human nature." In the late 1850's English overtook Dutch as the most

studied Western language as the Japanese saw the source of enlightenment

shift to the West. (Yanaga, 70)

Industrialization and trade had a huge effect on the people's normal

everyday lives. For instance, once sake became an industry

it took on a much different place in society. Whereas sake

used to be primarily home-brewed and saved for special occasion, industrialization

had improved both the quality and quantity giving rise to the local tavern

and along with it many of the social ills accompanying alcohol. Beer

also made an introduction into Japanese life with advertising starting

as early as 1872. However alcohol abuse soon led to consumption laws

outlawing sales to minors in 1922 (Yamagida, p.41). Tea also

had changed in this new era. It was during this time that Japanese

started the enormous consumption of tea. No longer reserved for tea

ceremonies or special times, tea became a staple of Japanese life (Yamagida.

p 44). Along with the explosion in tea came an even bigger sensation

in sugar. Previously very expensive, with the newly opened ports

sweets of all kinds started appearing in shops in the cities. Sugar

became so popular it had to be rationed and only then was it spread into

the countryside.

Before 1853 Japan was not only

closed to the outside world, but within the country, even individual fiefs

were isolated from eachother. As such if one region suffered from

a poor harvest or natural disaster, the effect would be devastating, costing

many thousands of lives a year. (Shibusawa, 57) But with the breaking of

the feudal barriers both internal and external, the rural food supply could

finally be stabilized. Being able to import rice, which only then

became a staple of the Japanese diet, bolstered supplies even more.

Consumption of rice steadily increased, especially in the cities, and

by 1882 rice had become Japanís main export. The opening of the foreign

market had made production profitable, and this in turn helped to stabilize

the price at home.

In all these different areas, and throughout

Japanese civilization at this time people found themselves inundated with

ideas and technology and experiences that would have been only fantasy

a generation before. In each case, they found ways to apply new styles,

technology, and ideas to their pre-existing circumstances and to make something

new come from it. Japan was able to adapt with so ferociously and

completely because it did not want to be left behind in the world it had

just re-entered.

|

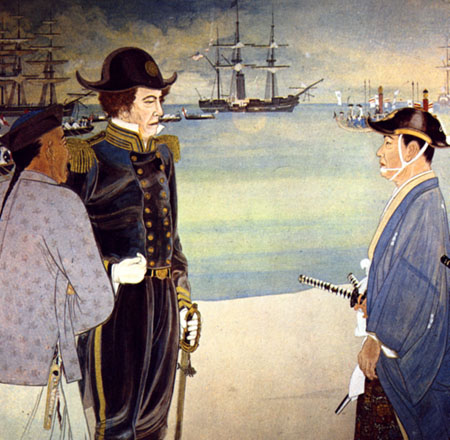

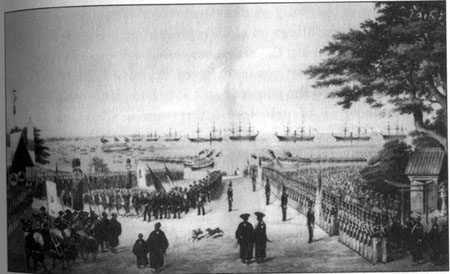

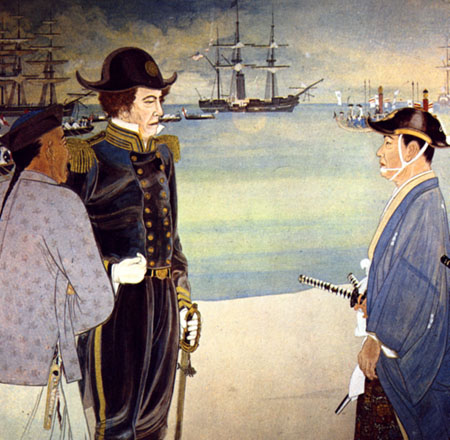

This

report will focus on the changes that occurred in people's lives after

Commodore Perry opened Japan to the outside world in 1854. From that

point on, the country quickly shifted from an antiquated feudal society

to one that looked forward with hope and expectation. In the Meiji

Era, people's lives took a dramatic change in several areas. However,

there were many ways in which traditionalism was still retained by the

people especially in the countryside. By the end of the Meiji era,

a new Japanese culture had started to arise as a synthesis of the rapid

modernization and traditional culture.

This

report will focus on the changes that occurred in people's lives after

Commodore Perry opened Japan to the outside world in 1854. From that

point on, the country quickly shifted from an antiquated feudal society

to one that looked forward with hope and expectation. In the Meiji

Era, people's lives took a dramatic change in several areas. However,

there were many ways in which traditionalism was still retained by the

people especially in the countryside. By the end of the Meiji era,

a new Japanese culture had started to arise as a synthesis of the rapid

modernization and traditional culture.

Many of the Japanese were quick to adopt western style both in their appearance

and actions. For example, the traditional Japanese hair cut for males

was the chomímage. This called for the head to be shaved except

for the rear, which was then pulled up and folded over the top of the head.

Thanks to its high maintenance and uncomfortable nature, it did not take

long for many men to switch to western hairstyles, especially those men

who were engaged in the new professions like school teacher, policeman,

or Meiji official. However, when the Meiji government finally came

out against the chomímage, some people fervently defended the old style.

There were even reports of mothers rejecting sons who came back from the

city or the army without their chomímage, and bridegrooms finding themselves

suddenly unworthy of their fiancées. (Shibusawa, 38)

Many of the Japanese were quick to adopt western style both in their appearance

and actions. For example, the traditional Japanese hair cut for males

was the chomímage. This called for the head to be shaved except

for the rear, which was then pulled up and folded over the top of the head.

Thanks to its high maintenance and uncomfortable nature, it did not take

long for many men to switch to western hairstyles, especially those men

who were engaged in the new professions like school teacher, policeman,

or Meiji official. However, when the Meiji government finally came

out against the chomímage, some people fervently defended the old style.

There were even reports of mothers rejecting sons who came back from the

city or the army without their chomímage, and bridegrooms finding themselves

suddenly unworthy of their fiancées. (Shibusawa, 38)