|

Communization of the Rural

Population

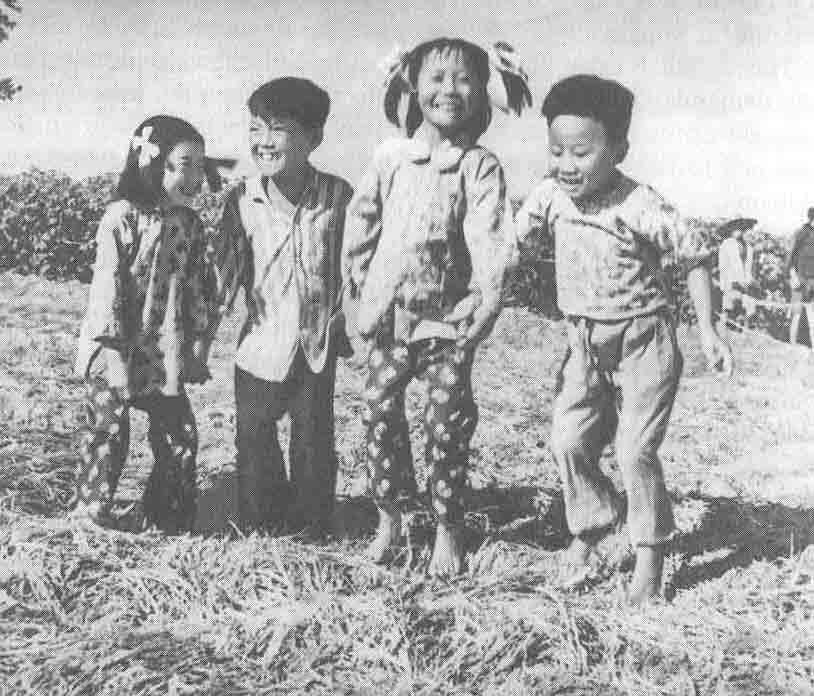

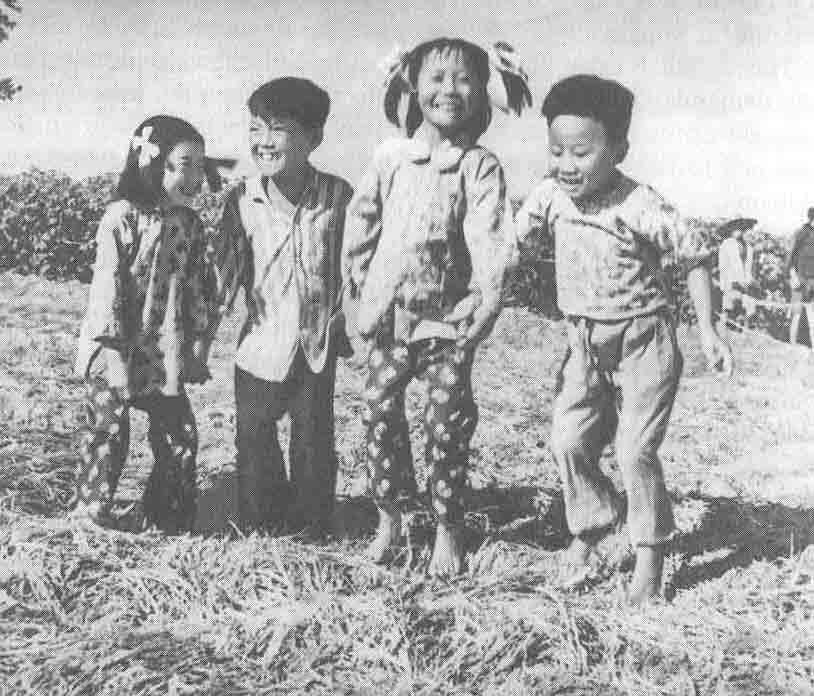

Having deemed

the existing cooperatives as too small to be optimally effective, Mao pushed

collectivization to the extreme beginning in the winter of 1957.

Whereas before the Great Leap, APC’s had consisted of several hundred people,

during this time, enrollment was increased so as to make each new commune

home to some 20,000 to 30,000 people (approx. 5000 families) (Soled, 62).

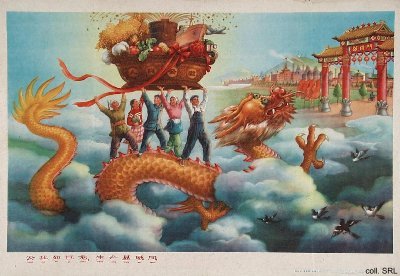

Of course, as is essential to the institution of any new Communist policy,

the CCP utilized mass propaganda techniques to cultivate ideological fervor

among the people. Mao did not want the people to be forced into these

communes; rather, he wanted the people to believe so strongly in the Communist

ideology that they would gladly voluntarily join worker’s communes.

Local propaganda plans that specifically dealt with the problems of the

respective areas and made widely unrealistic promises were used greatly

to implant the idea that Communism was the answer to all their problems. Having deemed

the existing cooperatives as too small to be optimally effective, Mao pushed

collectivization to the extreme beginning in the winter of 1957.

Whereas before the Great Leap, APC’s had consisted of several hundred people,

during this time, enrollment was increased so as to make each new commune

home to some 20,000 to 30,000 people (approx. 5000 families) (Soled, 62).

Of course, as is essential to the institution of any new Communist policy,

the CCP utilized mass propaganda techniques to cultivate ideological fervor

among the people. Mao did not want the people to be forced into these

communes; rather, he wanted the people to believe so strongly in the Communist

ideology that they would gladly voluntarily join worker’s communes.

Local propaganda plans that specifically dealt with the problems of the

respective areas and made widely unrealistic promises were used greatly

to implant the idea that Communism was the answer to all their problems.

Another major form of propaganda was the mass meeting led

by CCP cadres. Again, these one sided “debates” emphasized the greater

production that could result from communization, but they also took the

opportunity to emphasize the negative sides to the much smaller, ineffective

APC’s that were already widespread. Propaganda techniques were to

continue well after the establishment of communes as well. It was

a common practice for loudspeakers to be set up in communes so that the

peasants could hear political speeches that preached the great benefits

of Communism, while they were slaving away in the fields.

Despite the forewarning of such CCP officials as

Economic Planner Chen Yun and Premier Zhou Enlai who deemed the process

a “reckless advance,” the communization process was officially approved

by the Politburo in August of 1958. In total, roughly 26,000 communes

were quickly established throughout China, and by the end of 1958, all

but 2 percent of the rural population was part of one (Schirokauer, 607).

Even privately owned factories were converted into functioning communes.

The dynamics of the typical commune structure is actually rather interesting.

Within each commune, the agricultural workers were made part of two different

groups: brigades and team work units. Team units consisted of 12

families, and 12 team units formed a brigade. Regardless of structure,

all power truly lay in the hands of the Communist party cadres who were

responsible for setting a good example by partaking in the manual labor

along side the peasants. In turn, it was the party cadres who were

ultimately personally responsible for their commune’s production.

Despite the guise of relative equality, no decision could be made among

the commune, brigade, or team unit without the approval of the cadres.

As Chairman Mao stated when pushing the importance

of the communes, “Its (communes) advantage is that it combines industry,

agriculture, commerce, education, military affairs, and facilitates leadership”

(MacFarquhar, 81). Indeed, the individual communes did prove to serve

as the basic political, economic, and social units of China. Every

part of one’s life, right down to their banking, was handled through them.

They were their own self-contained communities in which everyone worked

and even ate together in communal mess halls. Interestingly, one

of Mao’s experiments with the communes was for payments for labor to be

made in kind. Thus, one worked largely only for the food they ate.

Separate policing, entertainment, schools, and hospitals could be found

in each commune as well. Education in the communes took an especially

unique path during this time. Wanting to move away from typical book

and rote memorization techniques of learning, Mao endorsed a “work and

study” program that served to encourage belief in the Communist ideology

while promising greater future educational opportunities (Lawrance, 58).

In addition, Mao believed that the communes themselves were advantageous

to national defense, for they already had the masses collected should war

break out. Everything seemed to be falling into place as planned.

With surprising ease, Mao had achieved the collectivization of the more

than 600 million rural workers in a very short time span. Despite

the fact that the question of their effectiveness remained to be tested,

the CCP held out very high hopes.

Industrialization Moves to the Communes

The second major aspect of the Great Leap Forward, the move towards greater

industrialization, also very quickly materialized. After the communization

drive, Mao, assuming his agricultural productivity success, turned his

sights toward increased steel production. Great strides had been

made in industry during the first Five Year Plan, and the CCP saw no reason

why the process could not continue to increase at the levels that it had

been (14 percent per year) if not at a far greater rate (Lawrance, 57).

Despite admitting that he knew very little about industry, to help increase

the growth and to utilize the full power of the communal system, Mao quickly

went about decentralizing industry. Over the course of the Great

Leap, nearly 80 percent of all enterprises were decentralized in Mao’s

efforts to forge a unique Communist path from the Soviet model (Schirokauer,

608).

The second major aspect of the Great Leap Forward, the move towards greater

industrialization, also very quickly materialized. After the communization

drive, Mao, assuming his agricultural productivity success, turned his

sights toward increased steel production. Great strides had been

made in industry during the first Five Year Plan, and the CCP saw no reason

why the process could not continue to increase at the levels that it had

been (14 percent per year) if not at a far greater rate (Lawrance, 57).

Despite admitting that he knew very little about industry, to help increase

the growth and to utilize the full power of the communal system, Mao quickly

went about decentralizing industry. Over the course of the Great

Leap, nearly 80 percent of all enterprises were decentralized in Mao’s

efforts to forge a unique Communist path from the Soviet model (Schirokauer,

608).

Following his belief that sheer numbers and the human

will could factor out the importance of skilled laborers and advanced technology,

Mao backed the movement of the steel industry into the communes.

A lesser degree of technology was brought to the countryside in the hopes

that the masses could help in the steel drive. What resulted was

the establishment of 600,000 “backyard furnaces” (Lawrance, 58).

These primitively put together furnaces were used to produce steel.

Members of communes utilized any means possible to contribute to the push

for greater steel production. All forms of metal were melted down

(often including personal pots and pans), and forests were leveled to provide

the fuel for these furnaces. However, because of the lack of technical

skill of much of the peasant population, the end result was highly inferior,

virtually useless steel. It was weak and not trustworthy enough to

build anything out of it. Nonetheless, it was factored into the production

calculation tallies. The legacy of these backyard furnaces has been

that they are illustrative of the Communist quest for quantity regardless

of quality.

Overestimation at All Levels

A root cause of the problems that were to be caused

by the Great Leap was undoubtedly the overestimation of production and

misreporting of numbers by party cadres. Only a few months into the

Great Leap, this trend was already apparent. Working off of inflated

production numbers for the summer harvest, at the 6th plenum of the Central

Committee in December, 1958, the party leaders raised the bar even higher

for production in 1959. Largely due to extremely good climatic conditions,

the grain production in China did rise considerably in the summer of 1958.

It is estimated that 200-210 million tons of grain were produced (Lawrance,

58). However, when reported to the Central Committee, the estimate

jumped to some 375 million tons! Such exaggerations were the trend

across the board. Steel production which totaled 5.3 million tons

was reported to be 11 million tons, coal production went from 130 million

to 270 tons with the stroke of a pen, and cotton production was inflated

from 1.6 million tons to 3.3 million (Lawrance, 58). These problems

of inflated production statistics were soon to catch up with the CCP.

In looking at the problems that the overestimation

of figures caused, it is essential to examine more closely what led to

this problem in the first place. Problems with the system appear

to be due to the fear instilled by the Communist party, or perhaps the

inherent nature of people not to want to disappoint their superiors.

Of course, the fact that the CCP played into the misreported statistics

certainly did not help. A fine example of the central government’s

role in miscalculations comes from some of the earliest communes, those

of the Honan province.

In early 1958, looking for an example of his vision

in practice, Chairman Mao directed his attention largely towards Honan.

Even before the communization effort had been approved by the Politburo,

efforts at forming larger communes from the existing APC’s had been taken

throughout China, but these efforts were particularly focused in Honan

because of its ideal geographic location. Honan was surrounded by

rivers, which interested Mao greatly because of his water conservancy plans

(Chang, 80). Supposedly, it was after a personal visit here that

Mao fully committed himself to the idea that communization was the correct

path for China to take. Throughout the Great Leap Forward the province

would serve as a yardstick by which all other communes were to be measured.

As a result, high amounts of government funding were channeled here, consequently

encouraging corruption and overestimation. All communes were to emulate

the manner in which these were run. Although it was to be merely

looked at as a pacesetter, because of the CCP attention focused on Honan

(the so called “cradle of communes”) and the funding benefits that they

received, these communes proved to be far more productive than typical.

Already higher production levels were further skewed through cadre exaggeration,

and government estimates were ultimately thrown off greatly (Chang, 81).

Throughout all of China, such was the case. Not wanting

to fall short of the estimates produced by the government, party cadres

found themselves faced with no real choice but to lie about production

levels or be deemed a failure. It turned into quite a vicious cycle

very quickly. Party cadres had two major reasons to over report actual

production. First of all, they did not want to be labeled a “white

flag,” or someone who was slow and conservative. On the flip side,

they wanted to be seen as “red flags” who were worthy of acclamation and

glory (Lu, 92). Consequently, it became common practice for cadres

to compete with one another to show that they had the most productive commune.

There is no doubt that the cadres felt the pressure

coming from the central government to exaggerate figures. Daily newspaper

reports on steel and grain production are illustrative of just how much

emphasis the government placed on output numbers. Cadres could thus

justify the falsification of statistics on the basis that it would only

help increase revolutionary fervor and ultimately the acceptance of the

Communist ideology. Perhaps one local official of the time summed

it up best when he said, “Without exaggerated reports, the momentum of

the Great Leap cannot be furthered; without exaggerated reports, the masses

will be humiliated” (Lu, 93). One can certainly clearly see the devastating

cyclical nature of the problem from such a statement.

Consequences for the General Public

Because of the tendency to exaggerate production

numbers, for a period in 1958 and 1959, the CCP believed that the Chinese

people would have a vast surplus of grain. Wholeheartedly thinking

that they held huge surpluses, Mao is said to have stated, “The state may

not want it (grain). Peasants themselves can eat more. Well,

they can eat five times a day” (Lu, 90). Taking him up on the offer,

it became the common practice for peasants to gorge themselves. Interestingly,

grain exports also remained at a steady rate of 4 million tons annually

during this time as well (Soled, 62). Only when Mao and other party

officials made personal visits to communes did the bleak reality set in

that there was not enough grain to sustain the current population, let

alone to permit them to use it extravagantly. The result was, of

course, mass starvation in 1959 and 1960 when the crop proved to be very

poor as a result of extensive flooding and other unexpected climatic problems.

Some estimates say that over 19 million people died between 1959 and 1960

and another 4 million are believed to have died of starvation the following

year (Soled, 63).

Obviously, the CCP did not want to admit the enormity

of their failure, so initial statistics that failed to include the amount

of capital that was invested in the various industries showed huge gains

across the board. Heavy industry was shown to have grown 230 percent

during the Great Leap, and steel production (including the poor steel of

the backyard furnaces) was said to have increased from 5.4 million tons

in 1957 to 18 million by the end of 1960 (MacFarquhar, 327). However,

when the real statistics finally came in, after the death of Mao Zedong

in 1976, the Great Leap Forward was proven to be anything but what its

name implied. Agricultural production, which had been the thrust

of the entire campaign, actually decreased in value 4.3 percent between

the years 1958-1962. Industrial production increased only 3.8 percent

in value. Overall, the national income fell by some 3.1 percent (MacFarquhar,

330). Perhaps most importantly, overall living standards would not

be at their 1957 level until eight years later. Party enthusiasm

had overlooked economic realities, and this cost China greatly. Despite

the enormous problems that the Great Leap caused, one striking positive

to come from it was the construction of numerous dams, roads, railways,

and irrigation plants.

Political Repercussions

Recognizing his part in the problems caused, Mao

resigned his post as President in April of 1959, and he was succeeded by

Liu Shaoqi. Nonetheless, for all intents and purposes, symbolically

Mao was still the man in charge; for he had been the father of the Communist

revolution and thus would always hold a place of high esteem. Elsewhere

within the CCP, the failures of the Great Leap brought about considerable

disagreement in regard to what measures should be taken for recovery.

At the 8th Plenum in Lushan in July, 1959, the realities of the state of

China were formally addressed, but more interesting was the shakeup caused

by Defense Minister Peng Dehuai.

Never afraid to stand up to authority for what he

strongly believed in, Peng viciously criticized Chairman Mao for his Great

Leap policies. Particularly questioning the backyard steel campaigns,

the use of communes without previous experimentation, and the continued

exaggeration of production numbers, Peng went after Mao immediately at

the conference, all but calling the Chairman a liar. As a response,

Mao hesitantly admitted that there were mistakes made in the communization

process, but these amounted to “only one finger out of ten” (MacFarquhar,

204).

Later in the conference, Peng laid out his complaints with

the economic failures of the GLF in a “letter of opinion” that was delivered

to Mao, and, some believe, distributed to all in attendance. In addressing

the letter, Mao surprisingly accepted most of the responsibility for the

major movements that had occurred as a result of the GLF. Essentially

the Chairman set up an “us vs. them” scenario in which he vowed that if

Peng was favored over him and the People’s Liberation Army favored him,

he would fight a guerilla war (MacFarquhar, 222). However, he had

no real reason to worry. Within only a few days, the fate of Peng

Dehuai was sealed. He was ousted as Defense Minister and put into

isolation. Lin Biao, a Mao extremist quickly assumed the vacant position

of Defense Minister.

Interestingly, even though the Lushan plenum had spoken

at length regarding the grave realities of the Great Leap Forward, few

CCP officials viewed the GLF as an outright failure. They pointed

to the fact that the irrigation methods instituted and the extensive building

of dams and roads would be of great significance in the long run.

Regardless, there was no chance that the policies would be continued, and

the CCP failed to pursue GLF policies past 1960. Premier Zhou Enlai

helped to draft the “Urgent Directive on Rural Work” which essentially

brought the Great Leap to an official end. The communes were shrunk

to about 1/3 of their peak size, and unrealistic production levels were

abandoned. By 1962, private plots were restored to much of the rural

population (Lawrance, 64).

|

Having deemed

the existing cooperatives as too small to be optimally effective, Mao pushed

collectivization to the extreme beginning in the winter of 1957.

Whereas before the Great Leap, APC’s had consisted of several hundred people,

during this time, enrollment was increased so as to make each new commune

home to some 20,000 to 30,000 people (approx. 5000 families) (Soled, 62).

Of course, as is essential to the institution of any new Communist policy,

the CCP utilized mass propaganda techniques to cultivate ideological fervor

among the people. Mao did not want the people to be forced into these

communes; rather, he wanted the people to believe so strongly in the Communist

ideology that they would gladly voluntarily join worker’s communes.

Local propaganda plans that specifically dealt with the problems of the

respective areas and made widely unrealistic promises were used greatly

to implant the idea that Communism was the answer to all their problems.

Having deemed

the existing cooperatives as too small to be optimally effective, Mao pushed

collectivization to the extreme beginning in the winter of 1957.

Whereas before the Great Leap, APC’s had consisted of several hundred people,

during this time, enrollment was increased so as to make each new commune

home to some 20,000 to 30,000 people (approx. 5000 families) (Soled, 62).

Of course, as is essential to the institution of any new Communist policy,

the CCP utilized mass propaganda techniques to cultivate ideological fervor

among the people. Mao did not want the people to be forced into these

communes; rather, he wanted the people to believe so strongly in the Communist

ideology that they would gladly voluntarily join worker’s communes.

Local propaganda plans that specifically dealt with the problems of the

respective areas and made widely unrealistic promises were used greatly

to implant the idea that Communism was the answer to all their problems.

The second major aspect of the Great Leap Forward, the move towards greater

industrialization, also very quickly materialized. After the communization

drive, Mao, assuming his agricultural productivity success, turned his

sights toward increased steel production. Great strides had been

made in industry during the first Five Year Plan, and the CCP saw no reason

why the process could not continue to increase at the levels that it had

been (14 percent per year) if not at a far greater rate (Lawrance, 57).

Despite admitting that he knew very little about industry, to help increase

the growth and to utilize the full power of the communal system, Mao quickly

went about decentralizing industry. Over the course of the Great

Leap, nearly 80 percent of all enterprises were decentralized in Mao’s

efforts to forge a unique Communist path from the Soviet model (Schirokauer,

608).

The second major aspect of the Great Leap Forward, the move towards greater

industrialization, also very quickly materialized. After the communization

drive, Mao, assuming his agricultural productivity success, turned his

sights toward increased steel production. Great strides had been

made in industry during the first Five Year Plan, and the CCP saw no reason

why the process could not continue to increase at the levels that it had

been (14 percent per year) if not at a far greater rate (Lawrance, 57).

Despite admitting that he knew very little about industry, to help increase

the growth and to utilize the full power of the communal system, Mao quickly

went about decentralizing industry. Over the course of the Great

Leap, nearly 80 percent of all enterprises were decentralized in Mao’s

efforts to forge a unique Communist path from the Soviet model (Schirokauer,

608).