Feng Shui was first used in China in the siting of graves.

It was important to site the graves of ancestors in good places that would

be unaffected by floods (water) and typhoons (wind). Feng Shui has

now become a very popular and practical design element in the western world.

Information about a specific site or room is gathered through sensing the

balance of yin and yang, and by using a feng shui compass. Traditionally,

yin is the dark, feminine, and receptive principle, and yang is the light,

masculine, and active principle. Together the yin and yang flow endlessly

into each other, and when balanced, can be appropriately applied to interior

spaces. A feng shui compass has an inner ring that is comprised of

eight trigrams (ba-gua). A trigram is a symbol made up of three stacked

lines, a solid line representing yang Ch’i, and a broken line representing

yin Ch’i. Creation of the eight trigrams is attributed to the legendary

Chinese king Fu Xi. He devised the eight trigrams through Taoist

observation of the natural world as seen on the patterns of a tortoise’s

shell as the animal emerged from the Yellow River. The eight tortoise

shell markings became the eight trigrams, which symbolize the natural world

as Heaven, Earth, Fire, Water, Lake, Mountain, Wind and Thunder.

Fu Xi laid out these eight symbols in an eight-sided map that became the

ba-gua, similar to a tortoise shell in shape. Each side of the eight-sided

map corresponds to one of the eight areas of life experience: career and

journey, knowledge and self-awareness, helpful people and travel, family

and health, children and creativity, wealth and prosperity, fame and reputation,

and relationships and marriage. By using the compass, the location

of each area of life experience can be determined.

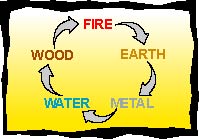

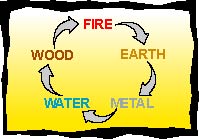

Taoist cosmology is structured on five natural elements: fire, earth, metal,

water, and wood. Everything on earth and in heaven is “characterized

by the constant interplay among the five elements, which are always moving,

unstable, and changeable, like the yin and yang” (Levitt, 21). In

Feng Shui, the balanced blend of all five elements creates a harmonious

environment. This is attained by applying the nurturing, controlling, and

reducing principles of the five elements. In the nurturing cycle

of the elements, fire nurtures earth because after fire burns it creates

more earth crust. Earth nurtures metal because metal ores are mined

from deep within the earth. Metal nurtures water because water is

contained and carried in metal vessels. Water nurtures fire because

adding wooden logs to a fire causes the fire to become bigger. Balance

is also achieved by applying the controlling element, in which fire controls

metal by melting it, and metal controls wood by cutting it. Wood,

in the form of trees, penetrates the earth and exerts an influence with

its roots. Earth controls the flow of water by blocking it with dikes

and dams, and water extinguishes fire. In the reducing cycle of elements,

fire burns wood, wood (trees’ roots) absorbs water, water corrodes metal,

metal is extracted from the earth, and earth suffocates fire. These

elements are allocated to different rooms in the home and to different

objects in order to facilitate the flow of the Ch’i.

Taoist cosmology is structured on five natural elements: fire, earth, metal,

water, and wood. Everything on earth and in heaven is “characterized

by the constant interplay among the five elements, which are always moving,

unstable, and changeable, like the yin and yang” (Levitt, 21). In

Feng Shui, the balanced blend of all five elements creates a harmonious

environment. This is attained by applying the nurturing, controlling, and

reducing principles of the five elements. In the nurturing cycle

of the elements, fire nurtures earth because after fire burns it creates

more earth crust. Earth nurtures metal because metal ores are mined

from deep within the earth. Metal nurtures water because water is

contained and carried in metal vessels. Water nurtures fire because

adding wooden logs to a fire causes the fire to become bigger. Balance

is also achieved by applying the controlling element, in which fire controls

metal by melting it, and metal controls wood by cutting it. Wood,

in the form of trees, penetrates the earth and exerts an influence with

its roots. Earth controls the flow of water by blocking it with dikes

and dams, and water extinguishes fire. In the reducing cycle of elements,

fire burns wood, wood (trees’ roots) absorbs water, water corrodes metal,

metal is extracted from the earth, and earth suffocates fire. These

elements are allocated to different rooms in the home and to different

objects in order to facilitate the flow of the Ch’i.

Another Feng Shui principle incorporates the

Chinese compass of north, south, east and west, in which south is located

on the top, and in the center of this compass is the “Middle Kingdom.”

The direction of south (summer) corresponds with warmth, heat, and vitality,

and its symbolic animal is the red phoenix, which represents beauty and

goodness. From the north (winter) comes cold snow and darkness, and

its symbolic animal is the black tortoise, which represents long life and

endurance. The direction east (spring), which is located on the left

side of the compass, corresponds to springtime, blue seas, and new growth.

Its symbolic animal is the azure dragon, which represents majesty and magnificence.

West (autumn) corresponds to snowy mountains, and its symbolic animal is

the white tiger, which exemplifies bravery and strength. These elements

are used for correct arrangement of furniture in rooms.

The essence of Feng Shui is to analyze the landscape, house office, garden,

etc, and to determine where the most favorable flows of Ch’i are located,

and then to work out how to produce new Ch’i of enhance existing Ch’i concentrations.

Mirrors are the most common interior means by which Ch’i is enhanced and

adverse sha is deflected. Mirrors should be positioned in areas where

the flow of Ch’i comes to a dead end. Mirrors intended to enhance

the flow of Ch’i should be placed at an angle, so that the path of the

Ch’i is directed further along its way. Mirrors meant to counter

sha should reflect it straight back out of the house. Sound is another

way of deflecting sha. Wind chimes, running water, or any melodic,

pleasing sound are all effective ways to deflect sha. The presence

of anything living, such as birds, dogs, cats, and plants, helps to ward

off sha. Sha travels is straight lines, so straight objects such

as fishing rods, armrests of chairs, and bamboo poles can be positioned

in a way to repel sha. Anything that moves in a breeze, such as flags,

banners, mobiles, and wind chimes, activate and disperse lingering sha.

The smoke for burning incense and gently flowing water also disperse sha.

Objects that are beautiful and enhance a sense of stillness and serenity,

“such as a statue of Buddha, Kwan Yin (the Chinese goddess of compassion

and mercy), the Madonna, or even a piece of driftwood or a particular stone,”

can reverse intrusive sha (Sharp, 76).

The essence of Feng Shui is to analyze the landscape, house office, garden,

etc, and to determine where the most favorable flows of Ch’i are located,

and then to work out how to produce new Ch’i of enhance existing Ch’i concentrations.

Mirrors are the most common interior means by which Ch’i is enhanced and

adverse sha is deflected. Mirrors should be positioned in areas where

the flow of Ch’i comes to a dead end. Mirrors intended to enhance

the flow of Ch’i should be placed at an angle, so that the path of the

Ch’i is directed further along its way. Mirrors meant to counter

sha should reflect it straight back out of the house. Sound is another

way of deflecting sha. Wind chimes, running water, or any melodic,

pleasing sound are all effective ways to deflect sha. The presence

of anything living, such as birds, dogs, cats, and plants, helps to ward

off sha. Sha travels is straight lines, so straight objects such

as fishing rods, armrests of chairs, and bamboo poles can be positioned

in a way to repel sha. Anything that moves in a breeze, such as flags,

banners, mobiles, and wind chimes, activate and disperse lingering sha.

The smoke for burning incense and gently flowing water also disperse sha.

Objects that are beautiful and enhance a sense of stillness and serenity,

“such as a statue of Buddha, Kwan Yin (the Chinese goddess of compassion

and mercy), the Madonna, or even a piece of driftwood or a particular stone,”

can reverse intrusive sha (Sharp, 76).

|

The principles of Feng Shui have existed for thousands of years.

Pictures of animals and symbols connected with feng shui have been found

which date back to prehistory. It has connections to many beliefs,

including Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Shinto, and Vashtu Shastri.

The principles of Feng Shui are based on precepts laid down thousands of

years ago in the Chinese classics, particularly the Li Shu, or Book of

Rites, a sacred book that enshrines the basic tenets of Chinese religious

belief. It is concerned with order, the harmony of heaven and earth,

and with the ways in which humanity can best keep the balance of nature

intact. In the nineteenth century AD, Yang Yun-sung compiled the

first manual of Feng Shui, systematically describing the characteristics

of scenic formations. This book became the standard text of the Form

School of Feng Shui. About a century later, scholars living in the

flat plains of the north composed their own answer to the problems of analyzing

the Feng Shui of mountainless regions, compiling a guide to another system

of Feng Shui founded on the symbolism of the points of a compass, which

came to be known as The Compass School. Today, Feng Shui experts

combine the two systems, “looking first at the undulations of the surrounding

countryside, and then consulting the compass to note the alignments of

the surrounding mountains and rivers with the spot under consideration”

(Walters, 11).

The principles of Feng Shui have existed for thousands of years.

Pictures of animals and symbols connected with feng shui have been found

which date back to prehistory. It has connections to many beliefs,

including Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Shinto, and Vashtu Shastri.

The principles of Feng Shui are based on precepts laid down thousands of

years ago in the Chinese classics, particularly the Li Shu, or Book of

Rites, a sacred book that enshrines the basic tenets of Chinese religious

belief. It is concerned with order, the harmony of heaven and earth,

and with the ways in which humanity can best keep the balance of nature

intact. In the nineteenth century AD, Yang Yun-sung compiled the

first manual of Feng Shui, systematically describing the characteristics

of scenic formations. This book became the standard text of the Form

School of Feng Shui. About a century later, scholars living in the

flat plains of the north composed their own answer to the problems of analyzing

the Feng Shui of mountainless regions, compiling a guide to another system

of Feng Shui founded on the symbolism of the points of a compass, which

came to be known as The Compass School. Today, Feng Shui experts

combine the two systems, “looking first at the undulations of the surrounding

countryside, and then consulting the compass to note the alignments of

the surrounding mountains and rivers with the spot under consideration”

(Walters, 11).

Taoist cosmology is structured on five natural elements: fire, earth, metal,

water, and wood. Everything on earth and in heaven is “characterized

by the constant interplay among the five elements, which are always moving,

unstable, and changeable, like the yin and yang” (Levitt, 21). In

Feng Shui, the balanced blend of all five elements creates a harmonious

environment. This is attained by applying the nurturing, controlling, and

reducing principles of the five elements. In the nurturing cycle

of the elements, fire nurtures earth because after fire burns it creates

more earth crust. Earth nurtures metal because metal ores are mined

from deep within the earth. Metal nurtures water because water is

contained and carried in metal vessels. Water nurtures fire because

adding wooden logs to a fire causes the fire to become bigger. Balance

is also achieved by applying the controlling element, in which fire controls

metal by melting it, and metal controls wood by cutting it. Wood,

in the form of trees, penetrates the earth and exerts an influence with

its roots. Earth controls the flow of water by blocking it with dikes

and dams, and water extinguishes fire. In the reducing cycle of elements,

fire burns wood, wood (trees’ roots) absorbs water, water corrodes metal,

metal is extracted from the earth, and earth suffocates fire. These

elements are allocated to different rooms in the home and to different

objects in order to facilitate the flow of the Ch’i.

Taoist cosmology is structured on five natural elements: fire, earth, metal,

water, and wood. Everything on earth and in heaven is “characterized

by the constant interplay among the five elements, which are always moving,

unstable, and changeable, like the yin and yang” (Levitt, 21). In

Feng Shui, the balanced blend of all five elements creates a harmonious

environment. This is attained by applying the nurturing, controlling, and

reducing principles of the five elements. In the nurturing cycle

of the elements, fire nurtures earth because after fire burns it creates

more earth crust. Earth nurtures metal because metal ores are mined

from deep within the earth. Metal nurtures water because water is

contained and carried in metal vessels. Water nurtures fire because

adding wooden logs to a fire causes the fire to become bigger. Balance

is also achieved by applying the controlling element, in which fire controls

metal by melting it, and metal controls wood by cutting it. Wood,

in the form of trees, penetrates the earth and exerts an influence with

its roots. Earth controls the flow of water by blocking it with dikes

and dams, and water extinguishes fire. In the reducing cycle of elements,

fire burns wood, wood (trees’ roots) absorbs water, water corrodes metal,

metal is extracted from the earth, and earth suffocates fire. These

elements are allocated to different rooms in the home and to different

objects in order to facilitate the flow of the Ch’i.

The essence of Feng Shui is to analyze the landscape, house office, garden,

etc, and to determine where the most favorable flows of Ch’i are located,

and then to work out how to produce new Ch’i of enhance existing Ch’i concentrations.

Mirrors are the most common interior means by which Ch’i is enhanced and

adverse sha is deflected. Mirrors should be positioned in areas where

the flow of Ch’i comes to a dead end. Mirrors intended to enhance

the flow of Ch’i should be placed at an angle, so that the path of the

Ch’i is directed further along its way. Mirrors meant to counter

sha should reflect it straight back out of the house. Sound is another

way of deflecting sha. Wind chimes, running water, or any melodic,

pleasing sound are all effective ways to deflect sha. The presence

of anything living, such as birds, dogs, cats, and plants, helps to ward

off sha. Sha travels is straight lines, so straight objects such

as fishing rods, armrests of chairs, and bamboo poles can be positioned

in a way to repel sha. Anything that moves in a breeze, such as flags,

banners, mobiles, and wind chimes, activate and disperse lingering sha.

The smoke for burning incense and gently flowing water also disperse sha.

Objects that are beautiful and enhance a sense of stillness and serenity,

“such as a statue of Buddha, Kwan Yin (the Chinese goddess of compassion

and mercy), the Madonna, or even a piece of driftwood or a particular stone,”

can reverse intrusive sha (Sharp, 76).

The essence of Feng Shui is to analyze the landscape, house office, garden,

etc, and to determine where the most favorable flows of Ch’i are located,

and then to work out how to produce new Ch’i of enhance existing Ch’i concentrations.

Mirrors are the most common interior means by which Ch’i is enhanced and

adverse sha is deflected. Mirrors should be positioned in areas where

the flow of Ch’i comes to a dead end. Mirrors intended to enhance

the flow of Ch’i should be placed at an angle, so that the path of the

Ch’i is directed further along its way. Mirrors meant to counter

sha should reflect it straight back out of the house. Sound is another

way of deflecting sha. Wind chimes, running water, or any melodic,

pleasing sound are all effective ways to deflect sha. The presence

of anything living, such as birds, dogs, cats, and plants, helps to ward

off sha. Sha travels is straight lines, so straight objects such

as fishing rods, armrests of chairs, and bamboo poles can be positioned

in a way to repel sha. Anything that moves in a breeze, such as flags,

banners, mobiles, and wind chimes, activate and disperse lingering sha.

The smoke for burning incense and gently flowing water also disperse sha.

Objects that are beautiful and enhance a sense of stillness and serenity,

“such as a statue of Buddha, Kwan Yin (the Chinese goddess of compassion

and mercy), the Madonna, or even a piece of driftwood or a particular stone,”

can reverse intrusive sha (Sharp, 76).