|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In order to understand the reasoning behind the various theories of sword construction one must first have a basic understanding of how they were used. The tradition of fighting with swords was probably transferred to Japan from China through Korea in the third century. The first known record of swords in the country is that of two which were given to queen Himeko from China during the Wei period in 280 a.d. Numerous schools of combat rose and fell, evolved and were destroyed throughout history. The most popular current style is known as Kenjitsu, derived from ancient Kendo, or the way of the sword. There are other styles that focus solely on the art of drawing the sword, and responding to surprise attacks.

A samurai sword is not formed from one solid piece of metal; rather it consists of many different parts that are fused together. This is necessary for two reasons: Different parts of the sword had special uses during combat, and the iron that was used had a tendency to become brittle when hardened. The samurai sword is a one bladed weapon. Contrary to many examples of stage fighting or that seen in motion pictures, the sharp edge of the blade was never used for blocking. In order to hold the razor edge it was given the metal needed to be extremely hard, which meant, in turn, that it was very brittle. If enough force was transferred from another bladeís edge dulling and even chipping could occur. Rather, the back edge was used to block a slash, and was, therefore constructed to be thicker and much less brittle.

A set of swords (daisho) were commonly worn in tandem by samurai, as can be seen in numerous photographs, paintings, and statues. The long sword was called a daito (twenty four inches or more), and the shorter a shoto (twelve to twenty four inches long). They were often mounted in identical koshirae (scabbards), the construction of which will be discussed later in this work. Many times there were small attatchemnts in these koshirae which housed more tools of the samurai trade. The kozuka was a small utility knife used much like a pocketknife would be today. Some of the more complex koshirae carried a kit called a kogai that was used for arranging hair and cleaning earwax. The wari-kogai was of similar design but was split down the middle so that it could also be used as chopsticks. The umabari was a triangular blade used as a throwing weapon that could be whipped out in a pinch. (2)

According to some legends, it is said that Samurai believed their swords had spirits of their own. As such, a strict code was developed for the use and everyday handling of their weapons. This is not hard to believe as such traditions were not exclusive to Japan, nor even to Asia. Warriors throughout the world have often attributed human characteristics to their weapons. The men whose job it was to make these swords were highly respected specialists. The tradition was often carried out by whole families generation after generation. Because the creation of a sword also meant the creation of a living creature, the smith was held to s strict moral and spiritual code, lest his inner corruption seep into the forms of his creations. To ensure this, the swordsmith underwent ritual fasting and purification before commencing his work.

The basic raw material used in all Japanese sword making was known as satetsu, which is a black sand-like iron oxide. This was then transmuted into steel by removing the oxygen and introducing measured amounts of carbon in a process called tatara, or smelting. The raw steel was sorted into lumps with different carbon amounts, so as to ensure that the proper material was used for the individual sections. These parts were then hammered into strips, wrapped in rice paper, and covered in clay to keep them in place before being heated and hammered to fuse it together. This was heated and hammered repeatedly to drive out impurities and air bubbles that would compromise the strength of the blade. It was during this phase that the signature wood grain effect is created on the blade. The shape these lines take can be changed based on whether the blade is folded lengthwise or breadth wise.

The process of tsukurikomi, or the way in which the different faces of the blade are fused together was extremely important. There were three basic ways in which this may be accomplished. The least complex (kobuse) way involved only two parts- a soft inner core and a hardened exterior. The next style (honsanmai) had four parts- the core, the sides, and the cutting edge. The most difficult form to create (shihozume) had five parts- the core, the sides cutting edge and the back (dull) side. The steel used for the exterior of the blade was high carbon and was typically folded thirteen to twenty times. The low carbon steel used for the core, in contrast, was only folded ten times. The edge was made from two special kinds of steel called tamahagane and zukuoroshigane, the latter of which was actually gleaned from old cooking pots and utensils.

After the various pieces were fused together

the smith then gave the blade its delicate swooping shape by heating and

hammering. This is done from the point first, working down to the

tang, which is concealed in the grip of the sword.

Next came the key process of overall hardening. A special

paste was prepared from clay, pulverized charcoal and crushed sandstone.

The sword would then be heated up until the exposed metal was a certain

shade of color. The weapon was plunged into cold water that would

instantly cool and harden the metal. The paste, however, allowed

the metal that it covered to cool much more slowly, thus maintaining its

softer and less brittle nature.(4) Gifted smiths would extend trails

of the paste down to the edge of the blade that created alternating sections

of brittle and soft parts on the cutting edge. This then kept damage

to the blade during combat to a concentrated area that could much easier

to fix than extensive breakage. It also created an aesthetically

pleasing wave pattern on the blade that added to the overall beauty of

the piece. The problem with this process is that it has a tendency

to make the blade bend. This meant that the sword maker had to take the

additional warping of the metal into account from the very first step in

the process. Often times the swords had to be re-worked anyway, as

it was difficult to gauge the exact degree to which the weapon would warp.

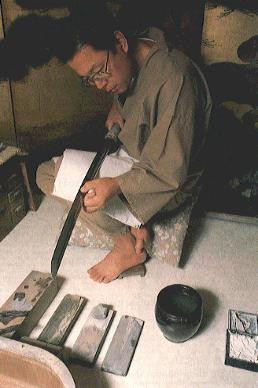

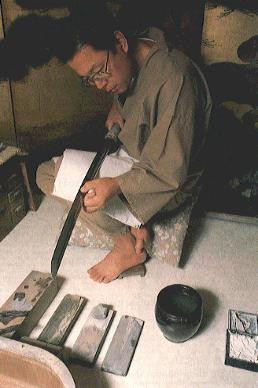

After the smith was done, the sword was sent to a professional polisher, who shined the blade and at times assisted in the final sharpening process with a variety of tools. A sword tester would then make sure that the weapon was of satisfactory quality. It is said that they would actually do these tests on the bones and limbs of corpses and condemned criminals. The information gained from these tests was then recorded on the blade by the tester so as to assure the buyer that the blade had attained a certain degree of quality.

This account is by no means universal. There

were numerous subtleties involved in the art that were both regional and

time specific. This was affected by the discovery of new techniques

as well as the use of different materials in different parts of the island.

Rather, this is a basic account of the steps that go together in the creation

of most blades.

There are six main time periods in which blades and their construction

styles are most commonly grouped (1).

· jokoto ('ancient swords') - 795

· koto ('old swords') 795 - 1596

· shinto ('new swords') 1596 - 1624

· shinshinto ('new new swords') 1624

- 1876

· gendaito ('contemporary swords')

1876-1953

· shinshakuto ('modern swords') 1953

Ė

As mentioned earlier, the koshirae, or and fittings which housed the blade are of particular interest. They could be very plain or very fine, depending on the social status or luck of the owner. They differed in quality and style, also, based on the occupation of the samurai. There were special designs of koshirae that were very extravagant and meant to be worn only in court. Much like the differences in equipment that can be observed in a palace guard in modern England and an airborne ranger, the samurai had different equipment specific to different duties and situations. The typical koshirae was made up of many parts, all of which were created by separate specialists who devoted their lives to learning their particular art form. These parts included the handle of the katana (the part which covers the tang of the blade), the actual scabbard that the blade sat in when not drawn, the attachments that allowed the sword to be slung from some part of itís wearerís person, and various other bells and whistles such as those already mentioned above.

The materials used in the construction of the koshirae were often both decorative and useful, an advantageous trait displayed by the craftsmen of the time in Japan. The scabbard, for instance, could be made of beautifully lacquered wood which happened to be waterproof; an excellent idea given the islandís troublesome weather patterns.

A rich samurai or daimyo would oftentimes own several sets of daisho. These blades, in turn could have numerous separate koshirae to go with them for different times. While being stored, the blade itself was divested of its decorateive elements and fitted with a plain wooden handgrip and scabbard known as a shira-saya. Oftentimes these are found with information about the blade held within painted on them. The koshirae would then be fitted with a wooden blade for its storage. (3)

The samurai sword was an extremely complex weapon, both in its usage and construction. Much time and labor were involved in its creation. Consequently, when the blade was used properly, it became one of the deadliest tools of its time. The tradition of sword making goes back many hundreds of years, and is a testimony to the perfect balance of power and beauty that resides within the art.

(1) http://anime.jyu.fi/~saren/Docs/Sword.html

(2) http://www.japanesesword.homestead.com/files/glossary.htm

(3) http://www.japanesesword.homestead.com/files/mounts.htm

(4) http://victorian.fortunecity.com/duchamp/410/katana.html

(5) http://www.blackbeltplanet.com/WI/futen/

(7) http://www.samurai-archives.com/

Site Created by:

Michael Polczynski