|

History and Effects in Japanese Society |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This research paper focuses on the history, practices,

and effects of Shinto in Japan. It covers the origin of the religion,

the ideas upon which it was founded, and some of the unique aspects of

Shinto. The paper also discusses the peaks and valleys of Shinto

throughout its history, and gives some insight as to why these periods

occurred. It then talks about Shinto in present day Japan, how the

religion can be viewed in today’s society as well as in the future, and

the lasting significance of Shinto. In sum, this paper gives an overall

perspective of the history of Shinto, its main practices and beliefs, and

its continuing effect for today and years to come.

Throughout history, different nations and cultures experience a variety of ideas, concepts, and phenomena that usually come and go. Japan’s history indeed follows this pattern, as it has had its share of different beliefs and traditions that pass with time. Few ideas and concepts can endure the test of time and continue to be strong for over 2,000 years. Religion is one of those concepts, and the Shinto religion is certainly no exception. Serving as Japan’s indigenous religion, Shinto has played a significant role in the lives of the Japanese people, ever since the Jomon period in 200 B.C. It began as a village-based practice, centering mostly around group rituals and ceremonies. Shinto did not even get its name until the 8th century, and even then it was only to distinguish itself from other religions. It remained a strong presence in Japanese society through the middle ages, leading right into its peak during the Meiji Restoration. Even after World War II when the Shinto State declined, it still remained an important presence throughout Japan, as it continues to do today. The original ceremonies and rituals, performed over 2,000 years ago, remain one of the strongholds of Shinto in today’s society. Shinto is a unique religion that has stood the test of time, and will likely remain vital to the people of Japan for many years to come.

The origins and foundations of Shinto in Japan are a unique story themselves. The practices of the religion date back to approximately 200 B.C. during the Jomon period. At the time, religion in Japan was in a different stage than most people think of when it comes to organized religion. That is partially due to the fact that there really were no organized systems of religion. Most faiths in Japan concentrated on rituals, ceremonies, and cult-like activity, opposed to most religions and their practices that developed throughout history. This situation can explain why, unlike other religions such as Islam and Christianity, Shinto does not have a creator or sacred scriptures. Basically, it was created out of the rituals and ceremonies, much like the other religions in Japan. It is for these reasons that Shinto was not considered an organized, traditional religion at the time. The name ‘Shinto’ had not even been coined yet because this faith was primarily a folk tradition centered more around these rituals and ceremonies than actual beliefs. The religion itself was not referred to as Shinto until the 8th century, when it needed to be distinguished from the Buddhist beliefs that were competing with Shinto.

When a name was needed to distinguish this religion from others, the word

‘Shinto,’ which comes from two separate Chinese characters, was chosen.

First, ‘shin’ is the parallel of the native Japanese word ‘kami’, meaning

“divinity or numinous entity” (Blacker 4). The second part, ‘to’,

is used to write the word ‘michi’, which means “way.” Although both

meanings are important to the overall makeup of Shinto, kami carries the

weight of the religious beliefs. Essentially, kami is a term for

sacred spirits, signifying admiration for Japanese virtues and authority.

It refers to a wide spectrum of objects and ideas in society, ranging from

gods in heaven to natural phenomena, such as wind, thunder, and human reproduction

(Kato, p. 22). Often referred to as “The Way of the Gods,” Shinto

and its followers believe that their rituals and ceremonies serve as signs

of respect and affection towards the different kami, which is why these

activities have been so important to Shinto throughout its history.

When a name was needed to distinguish this religion from others, the word

‘Shinto,’ which comes from two separate Chinese characters, was chosen.

First, ‘shin’ is the parallel of the native Japanese word ‘kami’, meaning

“divinity or numinous entity” (Blacker 4). The second part, ‘to’,

is used to write the word ‘michi’, which means “way.” Although both

meanings are important to the overall makeup of Shinto, kami carries the

weight of the religious beliefs. Essentially, kami is a term for

sacred spirits, signifying admiration for Japanese virtues and authority.

It refers to a wide spectrum of objects and ideas in society, ranging from

gods in heaven to natural phenomena, such as wind, thunder, and human reproduction

(Kato, p. 22). Often referred to as “The Way of the Gods,” Shinto

and its followers believe that their rituals and ceremonies serve as signs

of respect and affection towards the different kami, which is why these

activities have been so important to Shinto throughout its history.

Before these rituals and ceremonies can be discussed in detail, an important facet of the Shinto rites must be covered: the shrine. The Shinto shrines are very sacred, revered structures that serve as a place to honor the kami. Originally, the kami were honored at places of importance in villages or jungles, often representing the first sighting or experiencing of a kami. However, the crowds began to grow tremendously at these ceremonies, and the need for larger venues arose. Large shrines were then built to house these meetings; in many cases, they consisted only of a large hall that could fit the worshippers. But as time went by and more shrines were built, they were decorated inside and also constructed with chambers where it is believed that the kami are symbolically present (Ono, p. 20). One of the most common, yet also important decorations in the shrines is the mirror. “It symbolizes the stainless mind of the kami, and at the same time is regarded as a sacred symbolic embodiment of the fidelity of the worshipper towards the kami” (Ono, p. 23). Some mirrors are also considered sacred ornaments of Shintoism. For example, the mirror at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo is valued very highly because it was a gift from Emperor Meiji. Mirrors such as these are always held in high regard when worshippers come attend the shrines for ceremonies.

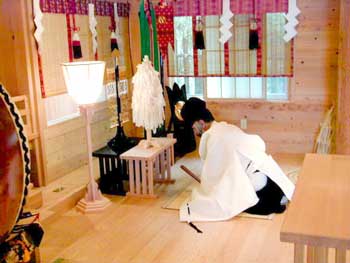

Next, the ceremonies that take place at these shrines usually involve four elements: harai, shinsen, norito, and naorai. Translated to English, they are purification, an offering, prayer, and a symbolic feast (Nelson, p. 180). The purification is intended to cleanse each person from evil, and is accomplished by rinsing out the mouth and pouring water over the fingertips. In addition to individual people being purified, some ceremonies include a purification of Japan or even the entire world. Next, an offering is made to please the kami spirits. Offerings include simple objects such as rice, salt, weapons, and jewelry; symbolic offerings are also made at these ceremonies, usually including a sprig from the sacred sakaki tree (Ono, 55). In addition, entertainment in the form of dances, wrestling, and archery are also viewed as offerings to the kami. Following the offerings, Shinto priests recite the ceremonial prayers, which usually begin with praise of the kami. Most commonly, the prayers then continue with a reference to that specific shrine, an expression of thanksgiving, and a closing remark of respect (Ono, p. 56). Finally, the sacred feast takes place at the end of the Shinto ceremony. The attitude is normally one of enjoyment and jubilation, as everybody gathers together for a meal shared with the kami spirits.

These shrines grew by the thousands all over Japan, and although they were all Shinto establishments, before the 19th century they were considered rather independent in their beliefs and practices. However, that all changed during the Meiji Restoration of 1868, as Shinto was named the official state religion of Japan. While many believed that Buddhism would be chosen, the Meiji oligarchs thought a return to Japan’s oldest religion was the best choice at the time (Reader 6). They saw it as a chance to unite Japan around a single concept that everyone could relate to, and also one with a significant amount of national tradition and heritage. Soon after Meiji State Shinto was introduced, its ideas starting spreading throughout Japan, infiltrating society through such entities as the military and educational system. It stressed that Japan and its citizens should be tied closely to one another, enforcing the idea of Japan as a family-state. These ideals and beliefs stayed present in Japanese society until World War II. After the defeat of Japan in 1945, State Shinto collapsed, and the religion itself returned to a weaker form that resembled Shinto prior to 1868. The thousands of different shrines steered away from widespread State Shinto, becoming more independent and even starting to form new religious denominations combining Shinto and Buddhism. The shrines that remained completely Shinto returned to older ways and traditions, focusing on ceremonies and community. This return to more traditional ways was called Jinja Shinto, or Shrine Shinto; it soon became the most popular practice of Shinto at the local and regional levels, and still remains that way today.

Although Shinto was still popular, it underwent significant changes in the second half of the 20th century. After 1950, an urban movement began to take place in Japan, as people soon realized that cities were the place to find jobs and make money. The Japanese started to produce steel and war tankers during the Korean War, and soon began mass production of goods for the United States, drawing people into the larger cities. This urban migration negatively affected Shinto because the rural, forest areas out in the country were the heart of Shinto, and people began moving away from their native religion. As Industrialization increased, the focus on religion decreased, causing worry among devout Shintoists. However, once people began to settle down in cities, shrines started to pop up in urban areas. Families once again turned to Shinto shrines for ceremonies and important religious events. Although these shrines encompassed variations of Shinto, combining Shinto and Buddhist beliefs, the tradition of Shinto continued to be prevalent in Japanese society. It remains that way today, and appears that Shinto will have a permanent affect in Japan well into the future.

Shinto is a very unique religion that can serve as a significant fixture in today’s society, both in Japan and throughout the world. People can relate to its past because the traditions that it was founded upon are what sustained the religion for over 2,000 years. Its community-oriented views and practices helped unite the Japanese people in the past, and still continue to do the same today. Shinto in today’s society has remained important because the Japanese understand the significance of native religious beliefs, especially when they are wholesome, religious convictions that stress a strong family bond and peace throughout the community. Shinto has stood the test of time, while at the same time proved its worth as a powerful, uplifting religion. Its traditions remain present in Japanese society, and will likely serve as a religious stronghold for many years to come.

Creemers, Wilhelmus. Shrine Shinto After World War II. Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1968.

Kato, Genichi. A Historical Study of the Religious Development of Shinto. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Mackerras, Colin. Eastern Asia: An Introductory History, Third Edition. Sydney: Longman, 2000.

Nelson, John K. A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Ono, Sokyo. Shinto: The Kami Way. Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1962.

Reader, Ian. Religion in Contemporary Japan. London: Macmillan, 1991

Robinson, B.A. “Brief History of Shinto.” Japan Research

Center. International Shinto Foundation. 18 March 2002 <http://www.asiasource.org/links/al_mp_03.cfm?TID=235>

At this site, you will be able to read more in depth about Shinto, and

also learn about the International Shinto Foundation.

Site Created by: Kevin Ratay