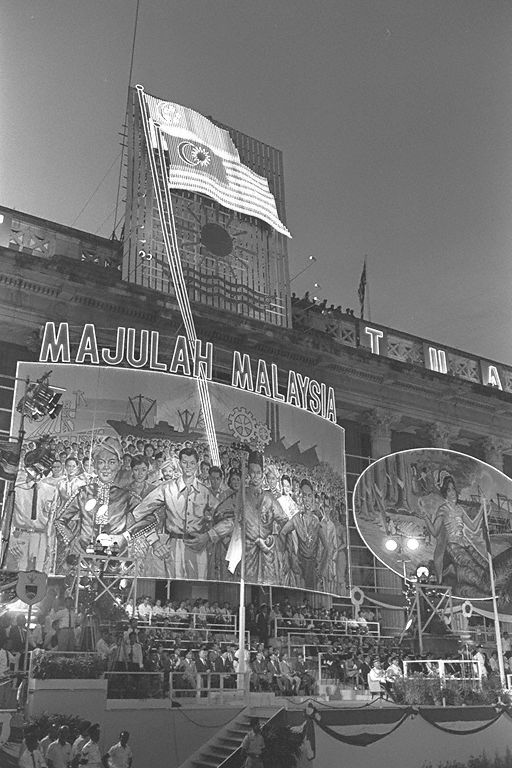

A parade in Singapore celebrating the merger (“Majulah Malaysia” means “Onwards Malaysia”)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

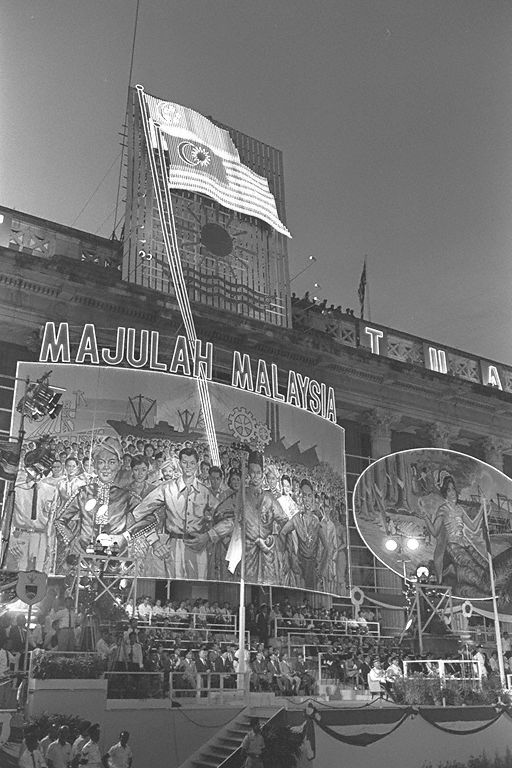

A parade in Singapore celebrating the merger (“Majulah Malaysia” means “Onwards Malaysia”)

The merger of Singapore into

the Federation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963 was never a happy story.

Right from the beginning till the inevitable separation of Singapore from

the Federation on 5 August 1965, the relationship between the two countries

was built under a foundation of political, economical, and social dilemma.

Through the Singaporean perspective, this paper investigates what are the

circumstances that led Singapore into the merger and its separation.

After the Japanese crushed the European powers in Southeast Asia during the Pacific War (1942-1945), it was not surprising to witness a sudden growth of anti-colonialism and nationalism sentiment within the region after the war was over. European colonies such as the Dutch East Indies, Malaya, and Indo-China began to engage and pressured their colonial masters for independence, as they no longer viewed them as their superior masters, and therefore unfit to govern them anymore.

In Singapore, the spirit of anti-British colonial rule was led by the communist-controlled PMCJA-PUTERA (Pan-Malayan Council of Joint Action-Pusat Tenaga Ra’ayat) coalition (Ernest C. T. Chew and Edwin Chew, A History of Singapore. Singapore, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, 120-122). But, it was a weak alliance. Less than two year after its formation (1946-1948), cracks started to appear, and the backbone of the coalition, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), was one of the first parties to exit.

Meanwhile, other independent parties, such as the Singapore Progressive Party (SSP) and the Singapore Labor Party (SLP) were more pathetic than the PMCJA-PUTERA. These parties were following the British like “running dogs” instead of opposing them. If they challenged the British, it would be on matters concerning “the closing of towgay (lit. “boss”) wells, seats for salesgirls, and smoking in the buses (Chew and Chew, 128).” This allowed the British to evade and prolong serious negotiations for the granting of full independence to the island.

Fortunately, things started improving in February 1954 when the British promulgated the Rendel Constitution that enlarged the electorate to around 300,000 voters. As a result, this revived the independence spirit among the parties in Singapore, and the social democrats led by English-educated professionals, such as Lee Kuan Yew, Toh Chin Chye, and S. Rajaratnam, together with the communists, formed the People’s Action Party (PAP). It was a left-wing party determined to fight for Singapore’s independence from the British (Raj Vasil, Governing Singapore: Democracy and National Development. SNW: Allen & Uwin, 2000, 19-20). However, there was a fatal clash of ideologies and power struggle between the social democrats and the communists within the party. This threatened the unity of the party, and thus jeopardized its crusade in fighting for Singapore's independence. After the PAP won the 1959 General Elections, the challenge of the communists became more intensified, and the social democrats believed that if merger with the anti-Communism Federation of Malaysia could not be achieved in the near future, Lee Kuan Yew, then the leader of the PAP and Prime Minister of Singapore, stated that Singapore government would fell into the hands of "a bunch of rogues [that] would ruin the [country completely]" and destroyed the independence dream once and for all (Chew and Chew, 138).

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of modern

Singapore

Initially, the merger was not well received in the Federation of Malaysia. Its Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman believed that the PAP should not view the merger as the solution for its campaign against the communists (Vasil, 25). He pointed out that alternate methods could be seen and achieved if the PAP was willing to cooperate with the British to solve this problem. In reality, the Prime Minister was worried that if Singapore were to join the Federation, its large Chinese population would create political and social instability, threatening the dominant Malay community in the Federation (Albert Lau, A Moment of Anguish: Singapore in Malaysia and the Politics of Disengagement. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998, 3). However, when the British proposed a new Constitution in 1959 that would grant Singapore full control of its government by 1963, the Federation's attitude toward the idea of merger started to take a turn.

The Federation was aware that if the British were to withdraw from the political scene in Singapore, the Singapore government would have to challenge the communists alone. Clearly, there was a risk that the government may not be strong enough to resist the thrust of the communists, and the result would see Singapore becoming a communist state, and in the eyes of the Malaysian, this would be a disastrous scenario, as Singapore could then served as an ideological base for the spread of communism into the Federation as well as other neighboring countries (Chew and Chew, 138).

The nightmarish image began to take shape in the Hong Lim by-election on 29 April 1961. The morale and strength of the PAP party was greatly questioned when the party was defeated by an independent party in a by-election (the Hong Lim by-election) (Chew and Chew, 140). Many PAP party members started to believe that the party as a whole was not that strong after all, and if merger could not be achieved, they were considering resigning their positions (Chew and Chew, 140). The "talk of resignation" alarmed the Federation, as it would allow the communists to come to power. On 27 May 1961, Abdul Rahman prevented the mass resignation by announcing to the Singapore public that "sooner or later," there would be a united Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak (Chew and Chew, 140).

On 15 July 1961, the PAP party was again in turmoil. This time, it was from within and the works of the communists faction of the party. When PAP was campaigning against the Worker's Party for a second by-election, the Anson by-election, the communist faction in the party publicly removed its support for the party and deflected to the opponent's side, before encouraging the social democrats to follow them. When the putsch was over, eight PAP Assemblymen deflected to communist side and the PAP lost the election (Chew and Chew, 141). The defeat left Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and Abdul Rahman in a state of shock. Fortunately, Lee was able to get back to his feet and reorganized the ranks of the PAP to prevent any future communist sabotage within the party. As a result, the communists were forced out of the PAP party, which then became the Barisan Sosialis party (BS) (Barbara Leitch Lepoer, “Singapore: A Country Study.” American Memory: Historical Collections for the National Digital Library. December 1989. Library of Congress. 20 April 2002. <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi bin/ query/ r?frd/ cstdy: @field (DOCID+sg0032)>.). Meanwhile, across the Straits of Johor, Abdul Rahman was Singapore's membership into the Federation (Chew and Chew, 141).

In the campaign to win support for the merger from the Singapore population, Lee believed that it ought to be achieved honestly through "a battle for the minds of the people, for the people's support, for what we believe what is right for the country (Chew and Chew, 142)." Therefore, he was willing to challenge the BS directly and openly with the usage of the press, radio, public forums, debates, rallies, and most important of all, political performance. Although the PAP party was greatly weakened by the events of the Hong Lim and Anson by-elections, under Lee's leadership, the party did not stop its promise to the people in improving the economy and society of the country. This was crucial to the party, as it won the hearts and mind of the Singapore population. Therefore, when the election of the merger was held on 1 September 1962, 70.8 percent of the electorate supported the idea, and Singapore, together with Sabah and Sarawak, became part of the Federation of Malaysia on 16 September 1963 (“Singaore: History,” International Information System 2002. University of Texas at Austin. 20 April 2002. <http://inic.utexas.edu/asnic/countries/singapore/Singapore-History.html>).

As soon as the merger was completed, the BS party started to fade from the political scene. So, both Singapore and Malaysia had scored a sweet victory over the communists. But shortly after their triumph, not only the relationship of the two countries became sour, but also they started turning on each other. And the standoff was caused by the economic, political, and social disputes between the two nations. However, it was not surprising to witness the deteriorate relationship. Right from the beginning, Abdul Rahman had pointed out that it was impossible for the Malay-oriented Malaysian government to get along with the multi-cultural ideology of the PAP party in Singapore. Therefore, the appearance of the disputes was just a matter of time, but no one expected that it would be that soon. Nevertheless, the following 23 months would be the most crucial point of the history of Singapore until the present.

The economical disagreements began when the Singapore failed to see the Malaysian government prior to the merger. Largely, it was because the Malaysian government was more interested in pursing its own trade expansion than to keep its words. As a result, Singapore was unable to trade with Malaysia in a common market, and this affected its economy. Besides, there was also a great deal of confusion and disagreement on how Singapore should contribute to the Federal treasury and development loans to the Borneo states. Furthermore, the Malaysian government forced the Bank of China in Singapore to close down (probably it suspected the bank was funding money for the communists) (Chew and Chew 144). Without the Bank of China, Singapore’s trade with China was greatly affected. Finally, the Malaysian government sidelined itself while Singapore tackled its unemployment problem and drained its savings to develop its industries (Chew and Chew, 144 and Barbara Leitch Lepoer, “Singapore,” American Memory: Historical Collections for the National Digital Library. December 1989. Library of Congress. 20 April 2002. ).

The unwillingness of the Malaysian authorities to work with Singapore to solve the economic problems was definitely not the honorable brother-to-brother relationship Lee was hoping (Lau, 17). Instead, it reflected a clear insult to Singapore. To make matter worse, while speaking to the Australian Deputy High Commissioner, Tan Siew Sin, head of the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) of the Alliance, stated that the Malaysian government was not interested in solving the problems in the near future, because Singapore’s economic growth “had gone far enough (Lau, 123).”

However, if the economical disagreements between Malaysia and Singapore were to be compared with the political disputes that they were engaging in during the 23-month period, they could be classified as minor problems. This is because the political clashes of the two countries were far more serious, and they even resulted in social unrest.

The earliest political dispute took place in the Dewan Ra’ayat (Malaysian House of Representative) over the number of House representatives. On the basis of the proportion of the Singapore population to the Malaysian population, the Singapore government was supposed to acquire 25 of the 149 seats in the House. Instead, it was only given 15. Furthermore, no member except Lee was given a post in the Malaysian government (Chew and Chew, 144). Again, it was another slap on the face for the PAP after the economic row, and evidently, the Malaysian government had the most obvious intention to shield the PAP from Malaysian politics. However, this time, the PAP had a different response, as it was determined not to be “cornered like a rat in Singapore (Lau, 91-92).” Therefore, the party decided to break its promise and participate in the 1964 Malaysian general election (Lau, 91-94). In a sarcastic statement, Toh Chin Chye, Chairman of the PAP, stated that this decision was necessary for the preservation of the party and forced the Malaysian government to employ a “more forward-looking social and economic policy” (Lee was not involved in this decision because he was away on a diplomatic mission in Africa) (Lau, 75-84). Unfortunately, the PAP was soundly defeated in the election, winning only one of the nine seats contested.

In the perception of the Malaysian government, the challenge of the PAP in the election meant a declaration of political war. The PAP had become an enemy with the desire to break the unity of the Alliance in the government and the social unity in the country. In response to the infiltration, the ultras (Malay extremists) in the United Malay National Organization (UMNO) of the Alliance, staged a retaliation campaign in Singapore. It called the Malay community in the island to unite and denounce the PAP. As a result, this resulted in two major racial riots in Singapore in July and September (Chew and Chew, 145). Undeterred by the actions of the Malaysian government, the PAP hit back. On 9 May 1965, the party with two Malaysian opposition parties (the People’s Progressive Party and the United Democratic Party) and two Sarawak parties (Machinda and the Sarawak United People’s Party) launched the Malaysian Solidarity Convention (MSC), with the aim of creating a “Malaysian Malaysia” against the existing “Malay Malaysia.” Lee even exerted, “[the ultras are] making a grave error if [they] think the people agreed to Malay rule in joining Malaysia (Barbara Watson Andaya, A History of Malaysia: Second Edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001, 288).” As a result, Lee and the PAP were able to create resentment between non-Malays and Malays in Malaysia. Reacting to the MSC movement, the ultra accused Lee that he did not have the intention to set up a “Malaysian Malaysia” but a “Lee Kuan Yew’s Malaysia,” and called for his arrest as well as the banning of the PAP. Fortunately, the interference of British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, prevented the disaster to occur (Chew and Chew, 146). As soon as the British were out of the scene, the ultra struck again. On 10 July 1965, during the Second Hong Lim by-election, the Alliance reenacted what the communists had done on the PAP in the first Hong Lim by-election by supporting the opponent party, the MCP (Andaya and Andaya, 287-288). But the PAP was able to win the seat by taking 58.9 per cent of the votes. It was confirmed, both countries were heading in a collision course, as the Alliance was against the PAP, and the PAP would never forgive the Alliance after this incident.

On 9 August 1965, the Dewan Ra’ayat was called to order, and Abdul Rahman passed the motion to “eject” Singapore out of the Federation “for no other reasons” than refusing to submit to a communal Malaysia. 126 of the 147 members in the House favored the motion, none against, one abstention, and 17 were absent. In Singapore, Lee acknowledged the “fateful” event to a packed press conference in Caldecott Hill, and choking with emotion, the Prime Minister ended with:

“Every time we look back on this moment when we signed this agreement which severed Singapore from Malaysia, it will be a moment of anguish. For me it is a moment of anguish because all my life…the whole of my adult life…I have believed in merger and the unity of these two territories…It broke everything we stood for.” (Lepoer).Singapore was out.

Singapore Today (An aerial view of the Central Business District (CBD) area of the island)

Albert Lau, A Moment of Anguish: Singapore in Malaysia and the Politics of Disengagement. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998.

Barbara Watson Andaya, A History of Malaysia: Second Edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001.

Ernest C. T. Chew and Edwin Chew, A History of Singapore. Singapore, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Raj Vasil, Governing Singapore: Democracy and National Development. SNW: Allen & Uwin, 2000.

Philippe Regnier, Singapore: A City-State in Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Synergy Books Internation, 1990.

http://inic.utexas.edu/asnic/countries/singapore/Singapore-History.html (A brief history of Singapore from colonial times to 1990)

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/sgtoc.html#sg0033 (A more detail study on Singapore, includes its population diversity, economy, politics, and etc.)

http://mi.essortment.com/historysingapor_ripo.htm (Another brief study on the history of Singapore from 1942-1960)

http://library.thinkquest.org/12405/20.htm (A site that points out the main events and figures of Singapore from its founding through present day)

http://www.sg/flavour/profile/pro-f_singapore1.html

(A very interesting page on Singapore, ran by the government. It

even includes a tourists’ information link)

Site Created by:

Tin Seng Lim