The world in which ukiyo-e

was born was dominated by the warlord government of the shogunate.

The Tokugawa implemented a social system of shinokosho, which stratified

society into four recognized classes of people in the following descending

order: warriors, farmers, artisans, and merchants. Each strata of

the shinokosho provided a service or product to society except the

merchant class (chonin) who created nothing and lived parasitically

off of the exchange of goods (Kita 28).

Chonin controlled a large

portion of wealth but were denied political power and legitimacy.

Considered oppressed due to numerous laws and restrictions, the government

of the Tokugawa realized the need to provide a “safety valve” to release

the resentment built amongst the chonin in such an obstructed society.

This safety valve would become known as the floating world (ukiyo-e)

which included the Kabuki Theater and Yoshiwara district where laws were

not enforced and the chonin could be free. These attractions

became the center of chonin culture and from this culture the ukiyo-e

print was born (Kita 29). These popular pastimes of the floating world

turned into popular artwork meaning to  capture

the fleeting scenes of a social class and appealing to more facets of the

population than any preceding art. The three main subjects of ukiyo-e

prints are the Kabuki Theater, Yoshiwara district, and landscapes. The

theater and brothel culture served as both an outlet for

chonin

to flaunt their wealth and alleviate frustration with the social order.

At the theatre chonin could patronize actors and fund productions

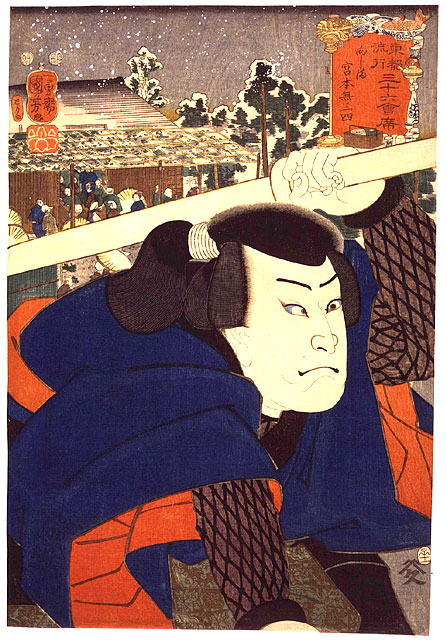

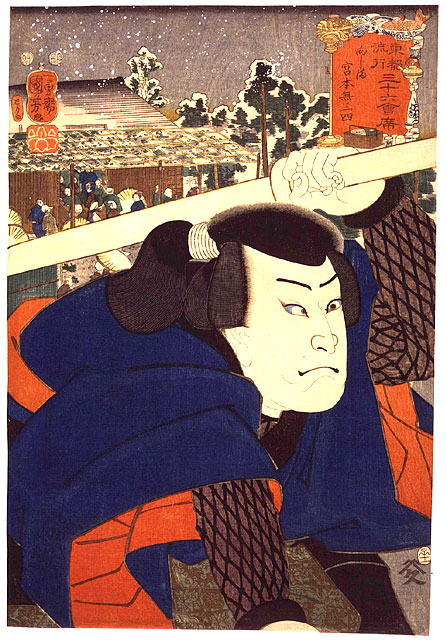

(Kita 38). Kabuki theatre is a type of Japanese theater comprised

of sixteenth century songs and dances originally performed by women and

men and then later exclusively by men. Lasting for hours the Kabuki

drama is saturated with action, numerous props, and elaborate costuming.

Dress, poses and gestures are highly stylized and the actors’ voices are

trained according to defined systems of modulation. Portraits of famous

actors and elaborate play scenes with props and costumes began to be produced.

These were often done in a close-up fashion and exaggerated facial expressions

(Adams 810). capture

the fleeting scenes of a social class and appealing to more facets of the

population than any preceding art. The three main subjects of ukiyo-e

prints are the Kabuki Theater, Yoshiwara district, and landscapes. The

theater and brothel culture served as both an outlet for

chonin

to flaunt their wealth and alleviate frustration with the social order.

At the theatre chonin could patronize actors and fund productions

(Kita 38). Kabuki theatre is a type of Japanese theater comprised

of sixteenth century songs and dances originally performed by women and

men and then later exclusively by men. Lasting for hours the Kabuki

drama is saturated with action, numerous props, and elaborate costuming.

Dress, poses and gestures are highly stylized and the actors’ voices are

trained according to defined systems of modulation. Portraits of famous

actors and elaborate play scenes with props and costumes began to be produced.

These were often done in a close-up fashion and exaggerated facial expressions

(Adams 810).

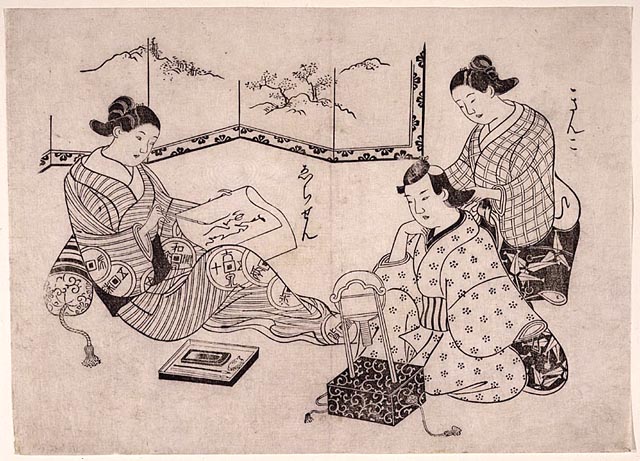

In the Yoshiwara district, wealth

could purchase female entertainment from the finest (oiran) to the

lowest courtesans (teppo) and gave chonin an opportunity

to act in the role of the aristocrat, quoting literature and commissioning

art (Kita 39). These courteasan beauties took center stage in the

prints and set the standards for popular trends with fashion and elegant

poses. Their images reflect an expression of mood and personality

shown in facial expression. Both of these images were highly idealized

and fantasized to meet the current aesthetic. Common scenes were

also captured such as domestic activities, festivals, even laundry (Kita

53).

In the second quarter of the nineteenth

century landscapes, which were once considered mere background, began serving

in the foreground to illustrate man’s place with nature. In

the traditional Japanese view humans do not control or attempt to dominate

nature, but instead attempt to live in harmony with all other creatures

and natural forces of the earth. This is especially exhibited by

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) one of the most famous landscape artists

of the 19th century whose Great Wave of Kanagawa is most recognizable.

There is a dramatic feel in the rise of the wave so close to the picture

plane towering above the men in boats who seem to bow to the wave (Addiss103-104).

This wave represents a temporary peak, which will fall in an instant but

Fuji in the center of the background remains, which is often linked, to

Japan’s sense of nationhood and patriotism (Baird 34) The other  famous

landscape artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) produced a series of travel

prints featuring the road between Edo and Kyoto, the Tokaido. As

more people began traveling this road from all walks of life, prints were

created for them to serve as souvenirs, records of travel, or even postcards.

These memories represented the spirit of Japan from the point of view of

the lower classes throughout seasons, weather, and times of day (Addiss

103-109). A Buddhist dissection of the term ukiyo-e reveals

two seemingly incompatible definitions: the floating world and the sorrowful

world. The floating world of pleasures does not appear to be sorrowful

at all however in a strictly Buddhist sense, a connection is discovered

through confronting the outlook on death. For most humans, there is fear

in the mystery of death and afterlife and one instinctually clings to the

material world. There is no afterlife in Buddhist teachings; Buddha

warns against clinging to life because of its temporary qualities.

Only sorrow results in humans’ futile decision to attempts to maintain

what naturally disappears. Thus the connection of the floating world

where one turns to the present transient pleasures of flesh and material

are by definition also a sorrowful world (Kita 56). This ukiyo-e

world is symbolically marked by the cherry blossom whose beauty may only

last a few days before being destroyed by rain or wind but are admired

for their impermanence and appreciated for their beauty. Incidentally

the type of wood traditionally used to carve woodblock is cherry (Addiss

99). famous

landscape artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) produced a series of travel

prints featuring the road between Edo and Kyoto, the Tokaido. As

more people began traveling this road from all walks of life, prints were

created for them to serve as souvenirs, records of travel, or even postcards.

These memories represented the spirit of Japan from the point of view of

the lower classes throughout seasons, weather, and times of day (Addiss

103-109). A Buddhist dissection of the term ukiyo-e reveals

two seemingly incompatible definitions: the floating world and the sorrowful

world. The floating world of pleasures does not appear to be sorrowful

at all however in a strictly Buddhist sense, a connection is discovered

through confronting the outlook on death. For most humans, there is fear

in the mystery of death and afterlife and one instinctually clings to the

material world. There is no afterlife in Buddhist teachings; Buddha

warns against clinging to life because of its temporary qualities.

Only sorrow results in humans’ futile decision to attempts to maintain

what naturally disappears. Thus the connection of the floating world

where one turns to the present transient pleasures of flesh and material

are by definition also a sorrowful world (Kita 56). This ukiyo-e

world is symbolically marked by the cherry blossom whose beauty may only

last a few days before being destroyed by rain or wind but are admired

for their impermanence and appreciated for their beauty. Incidentally

the type of wood traditionally used to carve woodblock is cherry (Addiss

99).

|

Evidence

of human desire to leave a mark upon the material world has existed as

art since the discovery of cave paintings created 35,000 years ago.

Techniques and style vary from culture to culture, but art acts as a keyhole

allowing glimpses into aspects of the contemporary society.

Social, political, and economic factors influence the production and content

of artwork throughout periods in history. Ancient Japan employed pottery

as an early and practical art form but as society became increasingly sophisticated

so too did its reflection in artwork. One of the most renowned types

of art produced in Japan is the woodblock print, which reached its Golden

Age in the Edo Period of 1600-1868 with the production of ukiyo-e,

pictures of the floating world. The term ukiyo can be defined literally

as floating world, a Buddhist concept referring to the transient pleasures

of material existence and e, the everyday pictures captured in printed

woodblock form (Addiss 95). This paper will examine the history of

the woodblock technique, the evolution and content of the ukiyo-e,

and the internal and external impact of the ukiyo-e movement.

Evidence

of human desire to leave a mark upon the material world has existed as

art since the discovery of cave paintings created 35,000 years ago.

Techniques and style vary from culture to culture, but art acts as a keyhole

allowing glimpses into aspects of the contemporary society.

Social, political, and economic factors influence the production and content

of artwork throughout periods in history. Ancient Japan employed pottery

as an early and practical art form but as society became increasingly sophisticated

so too did its reflection in artwork. One of the most renowned types

of art produced in Japan is the woodblock print, which reached its Golden

Age in the Edo Period of 1600-1868 with the production of ukiyo-e,

pictures of the floating world. The term ukiyo can be defined literally

as floating world, a Buddhist concept referring to the transient pleasures

of material existence and e, the everyday pictures captured in printed

woodblock form (Addiss 95). This paper will examine the history of

the woodblock technique, the evolution and content of the ukiyo-e,

and the internal and external impact of the ukiyo-e movement.

capture

the fleeting scenes of a social class and appealing to more facets of the

population than any preceding art. The three main subjects of ukiyo-e

prints are the Kabuki Theater, Yoshiwara district, and landscapes. The

theater and brothel culture served as both an outlet for

chonin

to flaunt their wealth and alleviate frustration with the social order.

At the theatre chonin could patronize actors and fund productions

(Kita 38). Kabuki theatre is a type of Japanese theater comprised

of sixteenth century songs and dances originally performed by women and

men and then later exclusively by men. Lasting for hours the Kabuki

drama is saturated with action, numerous props, and elaborate costuming.

Dress, poses and gestures are highly stylized and the actors’ voices are

trained according to defined systems of modulation. Portraits of famous

actors and elaborate play scenes with props and costumes began to be produced.

These were often done in a close-up fashion and exaggerated facial expressions

(Adams 810).

capture

the fleeting scenes of a social class and appealing to more facets of the

population than any preceding art. The three main subjects of ukiyo-e

prints are the Kabuki Theater, Yoshiwara district, and landscapes. The

theater and brothel culture served as both an outlet for

chonin

to flaunt their wealth and alleviate frustration with the social order.

At the theatre chonin could patronize actors and fund productions

(Kita 38). Kabuki theatre is a type of Japanese theater comprised

of sixteenth century songs and dances originally performed by women and

men and then later exclusively by men. Lasting for hours the Kabuki

drama is saturated with action, numerous props, and elaborate costuming.

Dress, poses and gestures are highly stylized and the actors’ voices are

trained according to defined systems of modulation. Portraits of famous

actors and elaborate play scenes with props and costumes began to be produced.

These were often done in a close-up fashion and exaggerated facial expressions

(Adams 810).

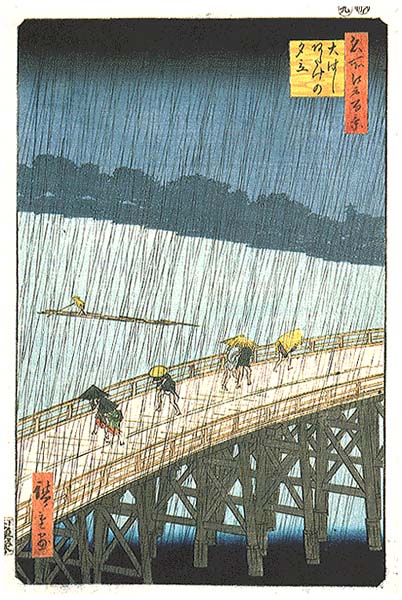

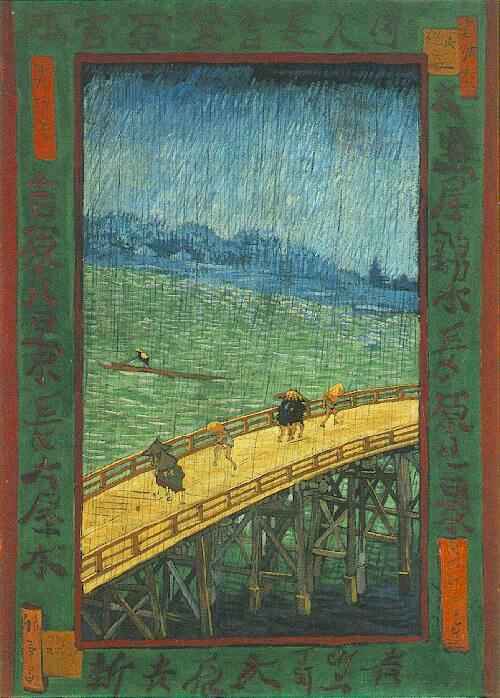

Stylistically

speaking the ukiyo-e print possessed distinct Asian qualities that were

adopted and adapted by Western painters. Ukiyo-e prints were distinguished

by oversized monumental figures filling the entire composition to really

bring the view into the picture. Gestures and poses were highly stylized

with elongated features distinguished by delicate black contour lines.

The perspective often times offers multiple viewpoints at once and disregards

traditional three dimensional space as depicted in Western art for flat

one-dimensional work. The strong diagonals greatly influenced the

work of Van Gogh as is seen in Japonaiserie: Bridge in the Rain 1887

after Utagawa Hiroshige’s Sudden Shower at Ohashi Bridge at Ataka

from the series One Hundred Views of Edo of 1857 (Adams 846).

Here one sees the influence also of the West on East with a linear perspective

of the one-point perspective. Filled with bold color woodblocks contain

spectacular costuming with amazing attention to detail of patterns in which

the Impressionist Mary Cassatt took an interest (Adams 822).

Stylistically

speaking the ukiyo-e print possessed distinct Asian qualities that were

adopted and adapted by Western painters. Ukiyo-e prints were distinguished

by oversized monumental figures filling the entire composition to really

bring the view into the picture. Gestures and poses were highly stylized

with elongated features distinguished by delicate black contour lines.

The perspective often times offers multiple viewpoints at once and disregards

traditional three dimensional space as depicted in Western art for flat

one-dimensional work. The strong diagonals greatly influenced the

work of Van Gogh as is seen in Japonaiserie: Bridge in the Rain 1887

after Utagawa Hiroshige’s Sudden Shower at Ohashi Bridge at Ataka

from the series One Hundred Views of Edo of 1857 (Adams 846).

Here one sees the influence also of the West on East with a linear perspective

of the one-point perspective. Filled with bold color woodblocks contain

spectacular costuming with amazing attention to detail of patterns in which

the Impressionist Mary Cassatt took an interest (Adams 822).

The

Impressionist movement of 1860-1920 was centered in Paris and was the antithesis

to the preceding period of Realism. Impressionists preferred to exchange

their ideas in Bohemian surroundings of cafes and bars because their movement

was initially seen as a challenge and was rejected by the Academy.

So too was the ukiyo-e print a first viewed as an illegitmated trend

separate from the sophisticated upper class. Being the first Japanese

art form to transcend social status ukiyo-e became popular amongst

people despite education or income level. Impressionist works

were consistent with the

ukiyo-e, depiction of genre subjects most

especially scenes of leisure activities, entertainment, and landscapes.

Impressionists took interest in the effects light had in varying weather

conditions, seasons, and time of day on subject matter as seen in the Hokusai’s

landscape series Thirty Six Views of Mt. Fuji where scenes in different

or similar views of the same place (Mt. Fuji) at different times of the

day and different seasons. Both movements’ compositions are chopped off

and asymmetrical which allows the viewer to feel as if included in the

image by catching a scene in motion similar to the photograph snapshot.

Impressionists began experimenting with a focus on flat color and patterns

and different poses inspired by woodblock patterned fabrics (Adams 805,

810-814).

The

Impressionist movement of 1860-1920 was centered in Paris and was the antithesis

to the preceding period of Realism. Impressionists preferred to exchange

their ideas in Bohemian surroundings of cafes and bars because their movement

was initially seen as a challenge and was rejected by the Academy.

So too was the ukiyo-e print a first viewed as an illegitmated trend

separate from the sophisticated upper class. Being the first Japanese

art form to transcend social status ukiyo-e became popular amongst

people despite education or income level. Impressionist works

were consistent with the

ukiyo-e, depiction of genre subjects most

especially scenes of leisure activities, entertainment, and landscapes.

Impressionists took interest in the effects light had in varying weather

conditions, seasons, and time of day on subject matter as seen in the Hokusai’s

landscape series Thirty Six Views of Mt. Fuji where scenes in different

or similar views of the same place (Mt. Fuji) at different times of the

day and different seasons. Both movements’ compositions are chopped off

and asymmetrical which allows the viewer to feel as if included in the

image by catching a scene in motion similar to the photograph snapshot.

Impressionists began experimenting with a focus on flat color and patterns

and different poses inspired by woodblock patterned fabrics (Adams 805,

810-814).