|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

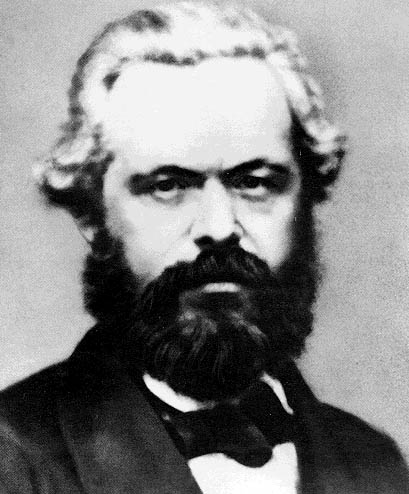

In a world full of conflict between liberal thinkers and their conservative

counterparts, Karl Marx was a breath of fresh air. Born in 1818, by the

1840s he was publishing his philiosophies on class conflict and economic

issues. His meetings with other philosophers, most notably Frederich Engels,

he created the foundation for his thinking and his writings. Marx's work

runs the gamut from economy to class to his contributions to sociology's

conflict theory. His philosophies on the constant struggle between classes

and the oppresion therein have been debated ever since his time. Were his

ideas feasible? Were they even a

possiblity in the 1840s and 1850s? Philosophers have debated for over

a century trying to decide if he ever had a workable plan in his philosophy.

Whether or not his ides were ever workable, he is remembered as one of

the great thinkers, philosophers, and sociologists of all-time.

In 1818, the German Rhineland unknowingly fostered into the world

one of the greatest thinkers of all time. Karl Marx’s birth in Trier to

parents of Jewish faith but liberal views was the beginning of a legacy

that still stands today. His parents, Heinrich and Henrietta were not endowed

with great wealth or overly radical views on things such as religion and

politics. They fostered his growth until his late teens when he left the

home. At seventeen, Marx went to study law at the University of Bonn. Having

been gone not even a year, Marx found himself already having been once

imprisoned for drunkenness and wounded in a scrap with another student

(Singer 2). At school, Marx’s interests quickly changed from law to philosophy.

He yearned for a more intellectual outlet in his studies. Marx found that

his parents could not support him for too much longer, so he set

to work on a thesis in hopes of receiving a university lectureship

which would offer a form of financial support (Singer 2). His thesis was

accepted but he was not offered a lectureship at the university. Marx turned

his attention to being the editor of a newly formed liberal newspaper,

the Rhenish Gazette. He wrote greatly appreciated articles for this newspaper

and eventually was chosen to head the organization when the original leader

passed away.

In 1844, Marx was trying to perfect his philosophical thoughts and his ideal political and economic theses. In the same year, he befriended Freidrich Engels. Engels, a German industrialist had come to be known as a great intellectual and a leading socialist. The two met in Paris and collaborated on a “pamphlet” called The Holy Family. The 300 page long document was Marx’s first publication. The reception to this work was not positive from governments in the surrounding areas. The Prussian government wanted the French to force Marx out of Paris (Singer 4). From Paris, Marx and family moved to Brussels, but he was forced to agree to stay out of politics in order to remain there. While in Brussels, Marx took an interest in the notion of classes within societies and the ways in which they affect and control the people living in them. Marx gained much of this interest from another philosopher, C. W. F. Hegel, a teacher at the University of Berlin from 1818 to 1831 (Singer 11). Hegel had written a work in which he analyzed the functioning of the mind and in which ways it differs from the spirit. In 1844, Marx wrote highly of Hegel and said that Hegel’s work in The Phenomenology of Mind was “the true birthplace of [his] philosophy” in Marx’s own Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844.

Through his work as a philosopher and his observations of society, Karl

Marx came to what may be likened to an obsession over the state of classes

within society. Marx made new arguments about the proletariat, or working

class, and its lack of control. He claimed that the formation of classes

went hand in hand with the need for production and that this need

Through his work as a philosopher and his observations of society, Karl

Marx came to what may be likened to an obsession over the state of classes

within society. Marx made new arguments about the proletariat, or working

class, and its lack of control. He claimed that the formation of classes

went hand in hand with the need for production and that this need

facilitated the domination of the proletariat (Berlin 170). Marx went

about trying to show that the proletariat was alienated from society and

that even within the class itself, there were high levels of alienation.

He noted that alienation is not class-specific, as other classes were able

to experience it as well. Rather, he said that the proletariat embodied

total depravation in society and represented the plight of all humanity

in their inability to control their own destiny through socially accepted

means (Singer 22).

Marx’s obsession with the alienation of the proletariat was discussed in his work on Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. The proletariat, he said, were victims of human nature and greed. Marx asserted that private property degraded every sense. If people are able to own their own property, then the worth comes not from the beauty of the object but in its monetary worth (Singer 27). He thought that the abolition of all private property would allow the senses to be engaged in the things they should be engaged in, like beauty and actual worth. Liberating the senses from the rigid money-based world would allow people to appreciate the world in a truly human way (Singer 27). The bourgeoisie’s ability to make the proletariat a class that could not experience life in a human way led to a conflict over power.

Marx’s notion of what it

means to be the “ruling class” is a very lengthy theory and contains many

ideas that are familiar to most people. Having power involves maintaining

social interests and techniques for change (Miller 112). Marx wanted us

to see the relationship between those who have power and those that do

not. The relationship is akin to a master-slave

relationship. Slaves are held back by those in charge of them and are

thus unable to fully pursue their desires, except through risky and often

illegal means. Marx’s political theories are based on these notions. If

a ruling class does not want change, as Marx proposed was necessary, then

it cannot happen since they are in control of the means through which change

can

occur. Change is not likely to occur through simple means such as voting

if the ruling class does not want it to change in those ways (Miller 113).

Thus, the class that wants change must often engage in radical and seemingly

desperate actions in order to bring about the changes it feels necessary.

Marx attributed the title of “ruling class” to the bourgeoisie and the

idea of the class needing to be radical to the proletariat.

Marx did not always favor

outright revolution as a way to advance the cause of the underserved, as

in certain countries it was not feasible for it to be successful. Marx

analyst Richard Miller noted, “While Marx accepts that industrial workers

will sometimes resort to revolution, this can only be a mistake in advanced

capitalist countries(117).” Marx believes that change

can occur in certain advanced countries which foster economic transition.

In these capitalist countries, he asserts that through the growth of the

economy and interests between groups, universal suffrage is often enough

to ensure the potential for political change. As societies become more

advanced, the potential for change is greater. However, the countries in

Europe in the 1840s and 1850s were not being conducive to the idea of progressive

reform in their governing systems.

In the 1840s when Marx was

making most of his claims and sharing his ideology with the world, most

countries were not advanced enough to encourage the kind of political change

he says can happen in capitalist countries. Marx thought that workers were

forced to sell their labor power, regardless of the conditions and pay

they would receive as a result. Marx

did not think that there were enough options open to workers that would

encourage the kind of competition between companies that would in turn

lead to better conditions for the workers. They were stuck in a precarious

situation, either selling their labor and time or being unemployed.

Marx comes to see the proletariat as more than just a historical phenomenon, but as a paradigm for all of humanity (Avineri 52). Their plight, he claims, is universal and his explanation is meant to illustrate that they are the best example of oppression of a group of peoples. In the 1840s, it was not possible for lobbying to occur in order to get changes made. Marx took to looking sociologically at other factors that influenced the constant plight of the proletariat. He noted that institutions such as religion continued to keep the proletariat down. Religion, Marx said, was controlled by the affluent prosperous bourgeoisie and was meant to control the proletariat further by acting as an “opiate.” Marx noted that religion was crucial in trying to make the members of the lower class believe that they were put here for a reason. Religion served this purpose in its ability to make the lower class people think that their plight was not as bad as it seemed, but rather their lot in life given by God. He meant that oppressed workers would see religion as a sort of drug that would ease their misery. It diverted their attention away from their plight and suffering and focused it on an afterlife (Henslin 346). Marx’s thoughts on how to remedy the situation in Europe in the 1840s and early 1850s are what come to make up much of sociology’s conflict theory.

Marx’s contributions to sociological conflict theory may at first glance seem completely out of line with historical ccuracy, but his use of the conflict perspective is what enabled him to be most successful in gaining the support of certain groups. In assessing the power struggle between the ruling class and the proletariat, he takes issue with what defines power. He maintains that those in positions of power are not there due to superior abilities, but rather because they have seduced the lower class into thinking that their welfare is dependant upon keeping society stable (Henslin 163). The notion that the bourgeoisie had effectively “brainwashed” the proletariat into continuing to accept their given role had to be dispelled, according to Marx. He said that revolution was inevitable, and once the proletariat became conscious to what was going on, open resistance would occur. Marx thus called for a classless society in which people would not be in different levels, but would all have the same access to opportunities.

Marx’s desire for this classless

society never came true. Granted, it was attempted in communist Russia

to a point, his ideas were never really functional as a system. To many

“Marxists” today, his theories were well thought-out, but otherwise impossible.

The struggle of power is one that is timeless and would not go away simply

at the thinking of one man. Historian

Peter Singer asserts that “Marx’s impact can only be compared with

that of religious figures like Jesus or Muhammed“(1). He goes on to note

that four out of every ten governments in the modern world claim to be

living under and promoting a government based on Marxist ideas. In these

societies he is seen as a “kind of secular Jesus“(Singer 1). But the question

is brought up, why did his ideas never work?

Historians such as Peter

Elster still feel that Marx had some ideas that are functional in today’s

society. Elster states that if modified in some small ways, many of Marx’s

theories would be great guides to industrial reform and in a grander sense,

economic reform. Those who still like to break Marx down in a scientific

way are searching in the wrong places. Marx was a philosopher and in many

cases he was wrong. He often made predictions about economic crises that

turned out to be absolutely wrong and invalid. This just goes to

show that he was fallible (Singer 68). The rate of profit did not fall

as Marx predicted. Capitalism did not collapse because of its internal

contradictions as Marx predicted. Marx’s legacy is not so much in his ability

to correctly predict economic event, but in his ability to see the conflicts

between classes.

This is where Marx becomes more of a philosophic and sociological mastermind instead of the economic genius that many make him out to be. His legacy lives on in the consciousness of classes and the ability to make change through certain political devices such as universal suffrage in extremely capitalist societies. All of his theories managed to die out in a fairly timely manner after his death. Many branches of Marxism have been attempted around the world with examples being Soviet Marxism and Western Marxism, both of which failed. The problem is that after Marx’s death, while there were some great political leaders attempting to enact his theories, there was a lack of great thinkers (Elster 12). Marx’s ideas are not strictly enough adhered to in order for them to be functional in society, if they are even plausible at all. The debate will go on over whether or not his ideas could have worked in any time or any place. More recent attempts to enact Marxism in a society have fallen victim to obscurantism, utopianism, and irresponsibility (Elster 12). None of those are virtues set forth by Marx himself. Many people engaging in Marx’s ideas lose sight of the purpose of his ideas to begin with and fall into a trap of trying to find a ‘perfect’ or utopian society. Marx never advocated having a perfect society, but rather reforming the type of society that was dominating the world around the 1850s. The fact that many of his followers have lost sight of the original reasoning for his writing has led to the decline in true attempts at Marxism anywhere in the world. Sociologically and philosophically, however, he remains a mainstay in thought and practice. Karl Marx’s acute sense of underlying conflict allowed him to help create the conflict theory in sociology and remain one of the most respected thinkers in that field.

Avineri, Shlomo. The Social and Politcal Thought of Karl Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1968.

Berlin, Isaiah. Karl Marx. New York: Time Incorporated, 1963.

Elster, Jon. An Introduction to Karl Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1986.

Miller, Richard. Analyzing Marx: Morality, Power and History. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1984.

Singer, Peter. Marx. New York: Hill and Wang, 1980.

http://www.marxists.org - an archive of Marxist documents and background on the theories of Marxism.

http://www.anu.edu.au/polsci/marx/marx.html - a page dedicated to the theories of Marx. Includes information on modern Marxism and the Communist Manifesto.

http://www.trincoll.edu/depts/phil/philo/phils/marx.html - Information on Marx and much information on his relationship with Frederich Engels.

http://csf.colorado.edu/psn/marx/Other/Riazanov/Archive/1927-Marx/ - Copious amounts of information on Karl Marx and very detailed chapters outlining his thought.

http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/profiles/marx.htm

- A huge collection of Marx-related links.

Site Created by: Brian Spencer