|

Development as an Artist |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At the turn of the twentieth century, a

revolution was occurring not only in the world of industry, but also in

the world of art. This revolution was led by a small group of artists,

who refused to follow conventional guidelines and, instead, embarked on

a quest to discover their true passions. This expedition was led

by the overly ambitious Claude Monet, whose gorgeous works coined the name

for this particular movement and through whom a new world of possibilities

was opened for art. Monet and his band of followers allowed themselves

to influence and be influenced by society, along with other artists, in

order to depict a fleeting moment; Impressionism.

The Impressionistic movement does not owe its development to Monet alone, but also to several societal developments, without which the movement would not have been possible. The 1839 publication of French chemist Michel Eugene Chevreul’s De la loi du contrast simultane des couleurs or The Laws of Contrast of Colors was not only essential to the Impressionistic movement, but also provided a solution to the problems of dyeing textiles (“Michel Eugene Chevreul” 1). Chevreul believed that when two neighboring colors are seen together, they will appear as different as possible because a color will always cast a complementary hue on its adjacent color (1). For example, a red next to a violet will possess a green tinge because green is the complementary color to red. Due to this phenomenon, adjacent, non-complementary colors, as in the example, will appear impure; whereas, complementary colors will seem to brighten (1). This influenced painters to begin to use color to show contrast and shading, as opposed to adding the browns and blacks characteristic of Realism. This breakthrough in the use of color enabled Monet and his fellow artists to develop the use of complementary colors to show shading and light in their work, which caused their paintings to appear vibrant and intense.

Yet, another revolution in scientific technology vastly improved the storage of paint, which permitted the artist to work out of the studio; the basis of the Impressionistic movement. This newfound mobility was caused by the development of a tin tube to hold manufactured colors, of which more became available after this invention was implemented. Previously, an artist would have to grind and mix his own pigments with oil (Stauter 1). Any excess paint would then have to be stored in an animal bladder sack, which would then be plugged with a bone stopper to prevent oxidation (1). In 1841, American painter John Goffe Rand, who disliked this procedure, produced the first tin tube to hold oil colors (1). Originally, the tube was open at both ends, closed by metal pincers or solder, making it necessary to puncture the tube in order extrude the paint (2). By 1842 Rand patented a form of the modern tube, complete with shoulders and a sealable nozzle (2). This particular version of Rand’s tube was the one that revolutionized the art world. Using neat, clean, easily portable tubes of paint, artists could, for the first time, sensibly work outside in fields or even on boats. This mobility, made possible by the tin tube, was a hallmark of the Impressionists.

Impressionism not only focused on the use of color and outdoor settings, but also on the spatial portrayal of the subject on the canvas. This was made possible by the expansionist Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who was commander of the U.S. naval forces present in the China seas and a fervent supporter of expansionism (“Expansion in the Pacific” 1). In 1853 Perry underwent a diplomatic mission to Japan to deliver a letter from President Fillmore requesting minor trade concessions, which was accepted when Perry returned in February 1854 (1). This initiated the importation of Japanese block prints to the U.S. and Europe. The flat color, pattern, and lack of depth of these prints influenced the Impressionists’ use of bright color and lack of emphasis of dimension in their artwork (“Monet: Influences and Associates” 2). However, the Japanese prints did not merely influence Impressionists in general; they directly influenced Monet’s portrayal of his subjects and his use of color.

Although affected by modern societal developments, Monet was chiefly influenced by other artists and their approach to painting. The first artist Monet met was Eugene Boudin, who discovered the sixteen-year-old Monet drawing caricatures in his town of Le Havre ("Claude Monet" 461). In 1858 Boudin invited Monet to paint with him on the Normandy coast, which introduced Monet to painting outside (The Impressionists: The Other French Revolution). In addition, Boudin encouraged Monet to focus on the sky in an attempt to capture its continual changes and showed him the possibility of using a contemporary landscape for his subject (1). Clearly, Boudin was the source of Monet and the Impressionists’ style of painting en plein air, or outdoors, to capture their rapidly changing surroundings (May 16). Also, Boudin’s affect was visible in the Impressionists mantra: “truth, light, and modernity” (16). Monet’s choice of light as the primary subject matter was a reflection of Boudin’s emphasis on the sky, the source of light ( click to see image ). However, Boudin was not the only artist who impacted Monet’s choice of subject. Gustave Courbet, a leader of Realism, was deeply admired by Monet for depicting life through his own perspective. (“Monet: Influences and Associations” 1). Monet was most likely influenced by Courbet’s realistic depiction of the weather and environment, as seen in Courbet’s The Wave ( click to see image ). Although these artists played significant roles in the development of Monet’s subject matter, neither Boudin nor Courbet’s technique was utilized outright.

Just as Monet’s inspiration for subject matter was based upon the thoughts of several artists, his technique consisted of a conglomeration of ideas. One technically influential artist was Jean-Francois Daubigny, a landscape painter who also subscribed to the en plein air technique of painting (1). Daubigny used a rebellious tachiste manner of applying paint in mere blotches of color on the canvas, which Monet embraced and used it extensively in his paintings ( click to see image ). Eugene Delacroix, a renowned Romantic artist, used complementary colors in shadows and calligraphic brush strokes, both of which can be found in Monet’s work ( click to see image ) (2). Yet another artist who had a substantial influence on Monet was the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind ( click to see image ). Upon returning to his hometown in 1862, the twenty-two year old Monet met Jongkind, who was examining how light could alter a scene (2). Monet was not only influenced by Jongkind’s subject matter, but also his brushwork, which Monet rendered as being “fluent yet concise” (“Claude Monet” 461). Jongkind’s technique of controlled brushstrokes was undermined when Monet first experienced the works of Joseph Mallord William Turner in the 1880s after residing in England during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 (461). Turner’s works were extensive studies of atmospheric effects, which, contrary to Monet’s belief, led him “to paint not merely the seasons and the principal times of day but all the modulations in between” ( click to see image )(Hamilton 102). Also, Turner used free brushwork in his renderings of luminous, rich color harmonies, which Monet used in his painting style (“Monet: Influences and Associates” 2). This group of artists greatly affected Monet’s manner of painting; however, none of them noticeably preceded the work of the Impressionists.

Edouard Manet, associated with the Realists, was the true predecessor to the Impressionistic movement. Manet first established the fact that the artist is loyal only to his canvas, not the natural laws of the real world, which are different from those of painting ( click to see image ) (Janson 709). Due to this ideology, Manet was considered to be “a rebel against artistic conventions,” which won him widespread notoriety and fame (“Monet: Influences and Associates” 2). Manet’s insistence that brushstrokes and patches of color were an artist’s ultimate reality coupled with his revolutionary ideology reinvented the role of the canvas in painting (Janson 709-710). Instead of a window, Manet used the canvas exactly as it was; a surface covered with pigments, which must be looked at directly (710). From this development, Manet became known as “the maestro of avant-garde artists” (May 50). Monet adopted Manet’s ideology of painting and applied it to outdoor landscapes, which concentrated on the brushstrokes and color of the paint, not the actual subject (Janson 710). Although Monet borrowed heavily from Manet, among other artists, the style he developed was uniquely his own.

The basis of Monet’s style, the foundation of Impressionism, was the painting of light, especially on water ( Monet: Portrait of an Artist: Legacy of Light). In Monet and the Impressionists’ attempt to capture the essence of light, the actual objects in the painting were forgotten and a fleeting moment in time was depicted rather than an actual scene (The Impressionists: The Other French Revolution ). This innovative approach to painting led to the development of the Impressionist aesthetic, which emphasized visual perception as the subject of pictorial vision (Hamilton 99). In other words, Impressionism consisted of painting nature directly in order to capture an impression of what was seen; the artist’s perception of a given place at a given time (“Landscapes of Light” 2). Monet best described this definition by stating, “Landscape is nothing but an impression, an instantaneous one” (qtd. in May 32). In addition to radically altering the purpose of painting, the Impressionists also used significantly different techniques, originally developed from Monet’s vast repertoire of knowledge.

In general, the Impressionists used common subjects depicted by quick brushstrokes and bright colors (“Landscapes of Light” 2). More specifically, Monet used roughly brushed patches of muted color on a canvas primed with a light color in order to convey the largest masses (“Monet’s Work Methods” 1). The canvas, referred to as an ebauche at this stage, is only partially covered with paint (1). From either a dry or wet base ebauche, Monet began to emphasize forms using dominant values along with contrasting and harmonizing color schemes (1). Typically dabs of paint were used; though, Monet was known to have used strokes ranging from dappled touches and blots to calligraphic strokes and hooks of color (1). From this information, it appears as if Monet immediately developed his unique style, without any changes or various; nonetheless, this was not the case. Monet developed his style throughout his entire life with many variations and changes.

Monet’s first paintings were focused mainly on painting outdoors at the scene he was attempting to depict. The influence of both Boudin and Jongkind was particularly apparent in Monet’s public debut at the Salon, a prestigious French government exhibition of select contemporary works (“Collections: Claude Monet” 1). In 1865, Monet submitted two seascapes to the exhibition, including La Pointe de la Heve at Low Tide ( click to see image ) (Gowing 461). This depiction of the coast near Le Havre, Monet’s hometown, was based upon smaller, portable canvases completed outside at the scene (“Collections: Claude Monet” 1). Most striking was Monet’s portrayal of the muddy beach and the reflections on the bottom of the ominous clouds (1). In this approach, Monet was clearly using Boudin’s characteristic en plein air painting and emphasis of the sky. Conversely, the tidy, brisk brushwork seen in the rocks at the right of the painting resulted from that of Jongkind (Gowing 461). After the success of his first display at the Salon, Monet continued to experiment with various techniques of painting in an ongoing search to find the perfect portrayal of light.

In 1867 when the Salon rejected his Women in

the Garden life size painting, Monet began to experiment with different

points of view (461). New, high points of view were emerging through

both photography and Japanese block prints (Stinson 245). Monet used

this new development in his painting Terrace at Sainte-Adresse (

click to see image ) by approaching his subject from a high view point,

which was angled downward to barely suggest a top view of the people sitting

in the terrace (Gowing 461). Monet also did not use a central focus

in this piece; instead, he suggests the animation and multiplicity seen

by the viewer in daily life (461). The layout of the scene was based

upon the grid-like compositional structure of Japanese prints as an alternative

to that based upon a single, central object (461). While Monet continued

to employ individual, crisp brushstrokes, a trait of Manet, in order to

define forms in Terrace at Sainte-Adresse , he would soon begin

to use bright color along with freer, more abstract brushstrokes. Only

a year later, 1868, did this begin to appear in Monet’s On the Bank

of the Seine, Bennecourt (

click to see image ) (May 32). This piece best demonstrated his

work outside on figure paintings and “can truly be called his first Impressionist

landscape” (32). Bennecourt more definitively centered on the reflection

of light on water and marked the beginning of Monet’s romance with the

motif that would become a hallmark of his painting (32). Monet used

a network of brilliant color patches in order to create the reflection

on the river, which seemed just as realistic as the objects being reflected

(Janson 710). He also began introducing color into shadows, characteristic

of Delacroix, usually with soft blues (Gowing 462). This mirror image served

to strengthen the composition not by adding depth, but by unifying the

surface of the painting (Janson 710). The unification of the surface

was imperative to Monet’s success because it compensated for his lack of

depth and detail, which, until the Impressionists, was considered to be

a necessity in any high-quality painting. Monet’s selection of modern

settings was also becoming apparent in this painting as well as Terrace

at Sainte-Adresse, which includes people among houses and boats, two signs

of modernity.

In 1869 Monet’s observation of light and color intensified in La Grenouillere ( click to see image ) (Gowing 461). His free use of color and natural talent became apparent in this piece; although he did not think it finished at the time it was quickly painted (461). La Grenouillere also displayed the shortening of Monet’s brush strokes, as can be seen in the short lines of paint used to convey light on the water. The figures have now become even less defined than in previous works; they are merely suggestive additions to the play of light on the water, which was expertly devised to look identical to an actual lake.

Monet continued to develop this technique while residing in London during the Franco-Prussian War or 1870-71 (461). Upon his return to France in 1871, Monet worked on variations in weather and lighting, an aspect carried on from his previous paintings. A canvas completed in 1872 and shown at the Impressionists’ first group exhibition in 1874 entitled Impression: Sunrise was, according to Monet, a depiction of “sun in the mist and a few masts of the boats sticking up in the foreground” ( click to see image ) (qtd. in May 15). Impression: Sunrise was the essence of Monet’s shorthand used to represent certain atmospheric settings (Gowing 461). He used pure, bright color, applied to the canvas with short, quick brushstrokes to hurriedly capture the fleeting moment (May 16). This hazy, unfinished appearance caused one critic to comment with sarcasm, “Impression—I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it…Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape” (qtd. in May 16). The harsh reaction of this critic was not uncommon to those acclimated to find only refined, realistic pieces to be worthy art. Ironically, Monet chose the title Impression because even he considered it to be a mere sketch, not a complete painting (Gowing 461). On the other hand, other critics were more reasonable in their response to Monet’s radical painting, such as Jules Castagnary, who coined the name of the movement being displayed when he said:

If one wants to characterize them (the artists) with a single word which explains their efforts, one would have to create the new term, ‘Impressionists.’ They are impressionist in the sense that they render not a landscape, but the sensation produced by a landscape. (qtd. in May 16)Castagnary was correct in his assumption; indeed, Monet had painted his response to the sunrise over the harbor of Le Havre. Although Monet still mainly produced more refined pieces, he began to concentrate more on light and less on actual objects, resulting in a change in his application of paint.

Throughout the 1870s most of Monet’s work was set in the town of Argenteuil, where he spent his summers perfecting the intense sunlight (Janson 710). His subjects also continued to concentrate on the modern, particularly industry and mechanization as can be seen in the busy harbor of Argenteuil, which was becoming industrialized at that time (Gowing 463). This was illustrated in 1875 in Monet’s Red Boats, Argenteuil , whose vivid yet subtle nuances of color suggested the effect of the light on the setting ( click to see image ) (462). In addition, to the development of the gradation of color, Monet began to alter his brushstrokes, which became flecks of paint instead of flat lines (Janson 710). While the brushwork became freer, each color and stroke of the brush still had a precise placement within the scheme of the painting; a somewhat intuitive approach was needed to successfully use this method (710). During the 1870s Monet expanded upon and clarified his points of concentration; whereas, in the 1880s Monet took his painting in an entirely different direction.

Monet, who had entered his forties, reinvented

his painting from the ground up. He discarded the theme of modernity

and began to look toward the timeless motifs of landscape for inspiration

(May 49). Monet also began actively seeking out dramatic weather

conditions in places such as Normandy, Belle-Isle off Brittany, Massif

Central, and the Mediterranean (Gowing 463). Along with new, unpopulated

scenes came the emphasis on the vertical as opposed to the horizontal seen

in his earlier works (463). Varengeville Church, Morning Effect

painted in 1882 was an outstanding example of a high viewpoint and a dramatic

contrast in scale, both associated with Monet’s revision of subject matter

( click to

see image ) (463). He began using a richer, more powerful color

scheme, in which even shadows were colorful and opposition as well as harmony

was used to express the surrounding light, as seen in the aforementioned

painting (463). In order to fully display this effect, Monet’s brushwork

became for more elaborate as can be seen in his 1886 work Storm on Belle-Isle

( click to

see image ) (463). In this artwork, Monet used sweeping strokes

to tie the painting together, display the violence of the storm, and create

an interesting surface pattern on the canvas (463). By altering his

style of painting, at last, Monet rose to the fame he knew would be his

by transitioning from a revolutionary to a master (May 50). His transition

involved reworking paintings in the studio in order to add the final touches,

such as emphasis of the unification caused by color and the pattern on

the surface of the canvas (Gowing 463). This aspect of his work became

even more important as he, once again, began to change his subject matter

(463).

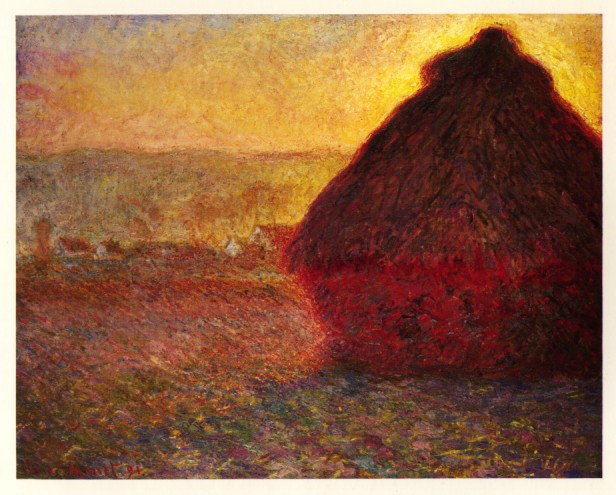

In the 1890s, Monet started working on series of paintings of the same subject in different lighting conditions and, sometimes, different perspective (Hamilton 102). Although he had been known to paint multiple views of the same scene previously, Monet had not used an entirely picturesque subject to convey the atmospheric effects that were his passion, nor had he exhibited his series together (Gowing 464). During this time period, he intentionally painted series of the same subject for group display in an exhibition (464). The first of Monet’s true series was Wheatstacks , in which he displayed the play of light on and around regular, unimportant wheatstacks observed near his home at Giverny ( click to see image ) (May 60). In these paintings, Monet simplified the perspective; the foreground, middle ground, and background were laid out in horizontal bands, causing a decorative effect (Hamilton 102). Additionally, he presented his objects only through the light reflected from them, resulting in the dissolution of the form in light; however, this correlated his belief in portraying the artist’s perception to the painting (107). Monet’s use of the Wheatstacks as means for artistic self-expression via perception led to “the notion that the artist can reconstruct nature according to the formal and expressive potential of the image itself,” one of the main views of modern art (May 61). Another means by which Monet exhibited his perception was in the series of Rouen Cathedral, which was completed from 1892-1894 ( click to see image ) (Gowing 464). This series of thirty canvases marked the growth of Monet’s more elaborate color schemes as a result of painstaking work in the studio, as well as the lack of brushwork characteristic of the 1880s (464). In fact, his work appeared to become slightly more abstract in this period; a trend that would continue on until the end of his career.

From the 1900s until his death in 1920, Monet focused solely on the water garden he created at Giverny (Hamilton 108). Initially, Monet concentrated on his Japanese footbridge and produced a series of the surroundings neatly divided by a distinct horizon ( click to see image ) (May 69). However, the use of a horizon was short-lived; by 1903 Monet painted only the surface of his beloved pond without any regard to the conventional use of space (69). Monet essentially became obsessed with the movement of water caused by wind along with the reflection of clouds intermingled with the sight of the plants growing under the surface of the water, which became the emphasis of his huge canvases depicting nothing but water (Hamilton 108). In his painting Water Lilies , the surrounding foliage was merely suggested by its reflection in the water, indicating the loss of a horizon ( click to see image ). The focus of this painting was not the water lilies, but the reflective quality of the water; the water lilies simply orient the viewer to realize the existence of the water. While Monet’s canvases became more ambiguous, his eyesight continued to fail and his work became more time-consuming in the pursuit of perfection (May 69).

Regardless of the start of World War I in 1914, whose front was, at times, a matter of miles from Giverny, Monet decided to build a new studio to house the enormous canvases needed to complete his idea of making the pond the subject of a decorative series to wrap around a room (Gowing 464). He used six foot tall canvases outside as well as in his studio to create this continuous view of water, unbroken by a horizon (464). Monet’s composition Iris , developed form 1922-1926, was a prime example of his enlarged, decorative paintings ( click to see image ) (May 71). Although never used in the installation of the decorations in two rooms in the Orangerie in Paris, Iris displayed several characteristics present in his other panels (Gowing 464). The painting’s surface possessed depth that was thick and grainy, like stucco, which displays Monet’s more expansive, abstract brushwork (May 71). Through the use of skeins of color layered upon one another, Iris illustrated Monet’s perception of the abstractions present in color (71). Another example of Monet’s Water Lily decorations, Waterlilies, Green Reflection, Left Part , more fully displayed the striking, calligraphic strokes used to form the water lilies ( click to see image ) (Gowing 464). Though this painting was installed in the Orangerie, opened in 1927 after Monet’s death in 1926 at age eighty-six, and Iris was not, both exhibit a quality for which Monet was known, that mere speckles and dashes of paint slowly become part of an intricate whole depicting light as the viewer movers farther away from the painting (464). No matter what form his painting took, Monet consistently attempted to, as he described it in 1926, “render my impressions in front of the most fleeting effect,” by (qtd in Gowing 464).

Throughout his career, Monet underwent a process of elaboration and interpretation from the brilliant use of color in his first paintings to that of vivacious color harmonies seen in his later works (464). He burst upon the art scene, fresh with ideas from a variety of artists, with works such as On the Bank of the Seine, Bennecourt and utterly destroyed the centuries-old canon of seamless expression of the traditional subject matter hierarchy (May 73). Moreover, Monet released color from being only symbolic or descriptive to become a vehicle of expression (73). Not only was this a result of society and fellow artists’ influence on Monet, but it also influenced artists such as Paul Cezanne, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, among others, to look at painting from a different perspective in an attempt to capture their impression of light (“Monet: Influences and Associates” 1-3). Each one of these artists experimented with these ideas and participated in the Impressionist movement to some degree before altering their studies to develop a method unique to themselves, as did Monet. Since he founded Impressionism, the unique progression of his works toward more purely depicting changing weather and light was not a variation on the movement, but the maturation of the innovative heart and soul of Impressionism: the painting of light. Monet was responsible for changing society’s opinion of acceptable artwork, which, in turn, opened the door for the development of modern art. Overall, Monet’s slow development of Impressionism, fashioned from societal and artistic influences, created a bridge between classical and modern art, redefining society’s view of art and the guidelines by which artists painted, thus, opening a broad range of possibilities for his successors to explore.

“Claude Monet.” Biographical Dictionary of Artists. 1995 ed.

Hamilton, George Herald. 19th and 20th Century Art. New York: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1970.

Janson, H.W. and Anthony F. Janson. History of Art. 6th ed. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 2001.

“Landscapes of Light.” Art & Man. Sept/Oct. 1987: 2-3.

May, Sally Ruth. Impressionism & Post-Impressionism – The Art Institue of Chicago. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1995.

Portait of an Artist: Monet: Legacy of Light. Perf. Peter Ustinov and Kathryn Walker. MGBH Boston and Malone Gill Productions in association with Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1989.

Stinson. Art Fundamentals Theory & Practice. 7th ed. Madison: W.C.B. Brown & Benchmark Publishers, 1994.

The Impressionists: The Other French Revolution. Vol. 1. Screenplay by and Dir. Bruce Alfred. Perf. Edward Herrman. A&E, 2001.

“Collections: Claude Monet.” Kimball Art Museum,

Fort Worth, Texas. Online. Internet.

<

http://www.kimbellart.org/database/index.cfm?detail=yes&ID=AP%201968.07

> 11 April 2002.

“Monet: Influences and Associates.” Montreal Museum

of Fine Arts. Online. Internet.

<

http://www.mbam.qc.ca/education/en-monet_frequ.html > 11 April

2002.

“Monet’s Work Methods.” Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Online. Internet.

<

http://www.mbam.qc.ca/education/en-monet_frequ.html > 11 April

2002.

“Expansion in the Pacific.” Small Planet Communications

. Online. Internet.

<http://www.smplanet.com/imperialism/letter.html#American

> 8 April 2002.

“Michel Eugene Chevreul.” Color Museum. Online.

Internet.

<

http://www.colorsystem.com/projekte/engl/17chee.html > 11 April

2002.

Stauter, George A. “The Irrepressible Collapsible Metal Tube.” American Perfumer and Aromatics. December 1958. Online. The Tube Council of North America. Internet. < http://www.tube.org/History.history.htm > 8 April 2002.

“Claude Monet.” The Artchive. Online. Internet.

<http://www.artchive.com/artchive/M/monet.html

> 30 March 2002.

Site Created by: Jennifer Dienes