|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The diplomacy of the Crimean War dictated the military actions of the

war and signified a general European desire to maintain the status quo.

The break-up of the Concert of Europe through the war vastly affected the

outcomes of conflicts in Europe throughout the 19th century and began the

decline of international agreements in favor of alliances. The diplomacy

practiced during the Crimean War cannot neither be ignored or praised.

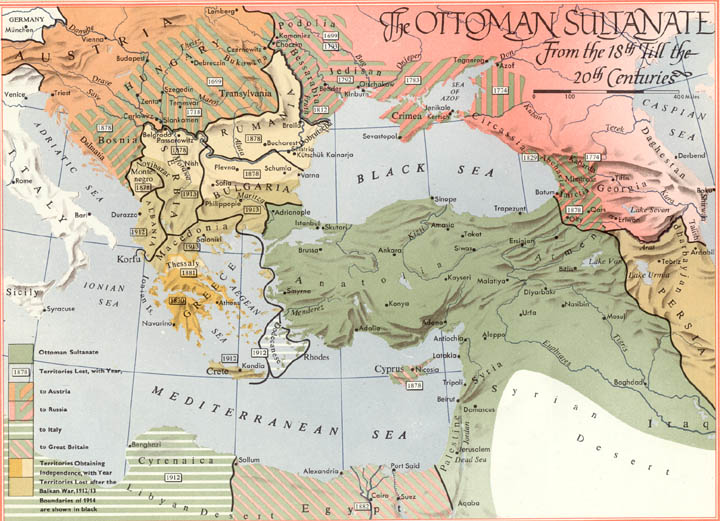

Every European history survey test mentions the Crimean War of 1853 to 1856, but few ever go into depth about the conflict that decided the prominent leaders of industry military and diplomacy. Most summaries of the war follow these lines: the Crimean War was a struggle between Russia and the Ottoman Empire over who should control the Turkish Straits and dominate the Black Sea. To some extent this is true; Russia’s greatest desire since Peter the Great was for a warm water port to induce trading abilities. The Ottoman Empire was declining and Russia saw its opportunity to achieve its goal. At the turn of the seventeenth century, the Ottoman Empire reigned over North Africa, the Middle East, a large portion of the Balkan Peninsula and all the land surrounding the Black Sea. Two hundred years later in the Black Sea, she only controlled the territory on the Southern shores of the Black Sea which included the strategic Turkish Straits (Baumgart 3). There were several sources of Ottoman weakness, the foremost of which were a geographical overstrain to control its vast territory, an assortment of religious and ethnic identities, a weak economy, corrupt governmental administration, and a disorderly military (Baumgart 4). In addition, when the Ottoman government, also know as the Porte, opened the Holy lands to all Christians in the 1830s, all European countries vied for political influence in this area, especially Russia, Britain, and France (do I need a citation here?). All three wanted influence in the area in order to facilitate new trade routes and markets. This in turn, lead to what is referred to as the “monks dispute” in which these countries argued over who had the right to restore and operate the Church and Grotto of Nativity in Bethlehem, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as well as various other Holy Places in Palestine (Baumgart 12). All of these religious and competitive tensions created an atmosphere of military outburst, yet physical conflict did not break out until the end of 1853. In the period before, during, and after the Crimean War, failed diplomacy dictated military action.

In 1844, negotiations between English Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, his

foreign secretary Lord George Hamilton Gordon Aberdeen, and the Duke of

Wellington with Russian tsar Nicholas I and his chancellor Count Carl Robert

Nesselrode resulted in a private agreement to maintain the status quo in

Turkey for as long as possible. However, should her fall seem imminent,

the two parties would open discussions concerning the possible dispersal

of the Empire (Henderson 3). This bargain was strictly personal,

involving only the five persons above and was unknown to the British Parliament.

Even so, it convinced Russia that the British would support a partition

of the Ottoman Empire when the time came. In December of 1852, Nicholas

saw his chance to commence these dialogues. Revolts in Montenegro

and increasingly heated disputes concerning the Holy Lands augmented turmoil

in the Ottoman Empire and triggered the Russian prediction of the death

of the Turkish “Sick Man of Europe” (Henderson 5). Moreover,

Aberdeen had just succeeded Peel as Prime Minister and initiated a new

cabinet. On December 29, 1852, assuming that the same previous amity

of 1844 was present, Chancellor Nesselrode broached the subject to the

English diplomat to Russia, Sir George Hamilton Seymour. What followed

was a series of tête-à-têtes between Seymour and Nicholas

called the Seymour conversations in which Nicholas openly expressed his

opinions and plans for the approaching disintegration of Turkey.

Nicholas’ honest desire was to prevent a European war over how the Empire

would be divided.

In 1844, negotiations between English Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, his

foreign secretary Lord George Hamilton Gordon Aberdeen, and the Duke of

Wellington with Russian tsar Nicholas I and his chancellor Count Carl Robert

Nesselrode resulted in a private agreement to maintain the status quo in

Turkey for as long as possible. However, should her fall seem imminent,

the two parties would open discussions concerning the possible dispersal

of the Empire (Henderson 3). This bargain was strictly personal,

involving only the five persons above and was unknown to the British Parliament.

Even so, it convinced Russia that the British would support a partition

of the Ottoman Empire when the time came. In December of 1852, Nicholas

saw his chance to commence these dialogues. Revolts in Montenegro

and increasingly heated disputes concerning the Holy Lands augmented turmoil

in the Ottoman Empire and triggered the Russian prediction of the death

of the Turkish “Sick Man of Europe” (Henderson 5). Moreover,

Aberdeen had just succeeded Peel as Prime Minister and initiated a new

cabinet. On December 29, 1852, assuming that the same previous amity

of 1844 was present, Chancellor Nesselrode broached the subject to the

English diplomat to Russia, Sir George Hamilton Seymour. What followed

was a series of tête-à-têtes between Seymour and Nicholas

called the Seymour conversations in which Nicholas openly expressed his

opinions and plans for the approaching disintegration of Turkey.

Nicholas’ honest desire was to prevent a European war over how the Empire

would be divided.

Despite Nicholas’ good intentions, the following year of Anglo-Russian communication between Britain and Russia through these ‘Seymour Conversations,’ terminated in rivalry and suspicion. Early in 1853, in a letter to the new foreign secretary of England, Lord John Russell, Nicholas divulged an elaborate proposal to partition the Ottoman Empire in which the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (located between the Danube and Pruth Rivers) would become independent as would Bulgaria; Serbia would become a Russian protectorate and Egypt and Crete would be annexed to England (www.mars.wnec.edu). In reply, Russell wrote to Seymour on Feb 9, 1853, that the fall of Turkey was a remote concern of England and that any arrangement for its division was more likely to cause war than to prevent it (Henderson 6). The British perceived Nicholas’ ambitions as greedy and audacious. Wanting to maintain the peace established after the revolutions of 1848, the English desired isolation and viewed Nicholas’ proposal with suspicion and anxiety. Nicholas had failed to understand the significance of the change in the British Cabinet along with the English request for isolation. As a result of his tactics of diplomacy, the British believed they were deceived by his so-called ‘good intentions’ and thereby lost all trust in the Russian ruler.

In the midst of these discussions with Seymour, Russia began to negotiate with the Porte as well. In February of 1853, Nicholas sent former Russian military leader, Prince Menshikov, on a mission to regain and guarantee Orthodox rights in the Holy Land (Baumgart 13). Essentially, the Menshikov Mission demanded the re-establishment of the honored position of Orthodox Christians living in the Empire and for a protective treaty which would give Russia an influential protectorate over the Porte. In three subsequent letters to the sultan’s Grand Vizier Mehemet Ali, Menshikov outlined the purpose of his mission, drafted the protective treaty, and suggested the creation of an Orthodox Church solely under Russian control to allow for increased Russian influence in the Holy Land (Royle 35). If Turkey did not agree, Nicholas threatened to cross the Pruth River and occupy the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. The Porte flatly refused to accept these terms and as a result Russia crossed the Pruth on July 20, 1853 (Baumgart 13). The tsar’s unreasonable and inflexible demands brought diplomatic failure and thereby necessitated military action.

However, Nicholas neglected to see the error in his provocative expectations and blamed Menshikov’s failure on British ambassador to Turkey, Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, who had advised the Porte not to accept Nicholas’ offer (Royle 52). At this point, Russia lost all western support for her foreign policies, especially in England. In light of these Russian accusations along with loose Otto-British alliance, the English government knew its previous desire for isolation was futile. In early June she sent a squadron of six warships to the Bay of Besika near the Dardanelles to protect Turkey in the event of a Russian attack (Royle 53). Wanting to facilitate a Franco-British alliance France followed this example by doing the same one day later. The failure of Menshikov’s diplomatic negotiations brought Russia, Britain and France to some degree of military involvement and to an increased rivalries among the three countries.

In spite of the appearance of pending military conflict, European countries still hoped to settle to dispute through diplomacy and uphold the decision to maintain a balance of power, the Concert of Europe, as declared by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The most vulnerable of these countries was Austria whose loyalty to Russia through the Holy Alliance of 1815 wavered upon increased Russian aggression in the Principalities and in the Balkans (Royle 65). More partial to a weak Ottoman Empire on her southern border than a strong Russian tsar, Austria offered to host a series of conferences in Vienna in an attempt to resolve the disagreements between Britain, France, Russia, and Turkey. From early July until the end of the year, France Britain and Austria produced 11 proposals for peace, the most important of which is the Vienna Note (Baumgart 14). Austrian foreign minister, Count Buol-Schauenstien, initially put forward the Vienna Note whose final text included the following arrangements: a joint Russo-Turkish concern for the well-being of the Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, a promise that the Sultan would respect the former, ambiguous treaties of Kutchuk Kainarji and of Adriainople, a promise to the Greeks to share in the advantages awarded to the Orthodox Christians, a reaffirmation to maintain the status quo in the Holy Land and to not disturb this status quo without combined consent of France and Russian, and finally a guarantee of the Russian right to build a church and hospice in Jerusalem (Goldfrank, 196). As Crimean author Trevor Royle states, the treaties of Kutchuk Kainarji and Adrianople justified “Nicholas’ contention that he had the right to be the protector of the Ottoman Empire’s Orthodox Christian subjects . . . [which] had formed the basis of demands made by Menshikov earlier that year” (Royle 66).

All seemed well. On July 31, 1853, France and Britain agreed to the terms specified by the Vienna Note. Russian acceptance was probable due to the Note’s subtle pro-Russian tone. On August 14, however, the Porte declined to sign the note, protesting that the suggested claim for Russian and French interference in the third point infringed on upon Turkish sovereignty. In addition, they objected to great powers’ audacity in taking it “‘upon themselves to draw up a note without the knowledge of the party more immediately involved’” (Royle 68). Although there were some minor revisions in this area, on September 20, 1853, the Porte officially rejected the note. This activated a host of military implications. Within a week, both the French and British sent a fleet to Constantinople to protect the Sultan (Royle 73). Russian troops remained in the Danubian Principalities, vowing to stay until a peaceful accord was struck. On October 4, in response to continued Russian presence in Moldavia and Wallachia, the Porte declared war on Russia (Baumgart 13). British and French interest in the Ottoman Empire appeared too strong to withdraw from the conflict and a large-scale confrontation seemed inevitable.

Despite continued negotiations for peace in Vienna, a solution acceptable to both Russia and Turkey could not be found. Coming to the aid of their “sick” friend, England and France declared war on Russia on the 27th and 28th of March 1854 respectively, pressuring her Germanic neighbors to do the same (Baumgart, 14). Such demands on Prussia and Austria was the source of many diplomatic interactions with Austria. Austria considered the Ottoman Empire as a safe buffer zone between her and Russia, especially in light of the suspicious Russian territorial advances in the Principalities and thus wanted to maintain the status quo in the Balkans. Yet, economically she was too weak to support a war which would be fought on her land and was still indebted to Russia for military aid in a Magyar uprising four years earlier (Royle 65). Even though neutrality was the goal, seclusion from the war was out of the question. Since she was dranw into an unwelcomed dispute, Austria tried to gain as much as she could from it and put forth her own war aims. As part of one of many failed peace treaties, she proposed the return of a strategic southern section of Bessarabia to the Principalities along with the exclusion of Russia from the navigable waters of the Danube River (Lambert 296). On June 3, 1854, after rejecting foreign alliance, Austria demanded that Russia leave the Balkan Principalities or be obliged to do so by force (Baumgart 17). Austria had hoped that this threat alone would induce peace talks, but instead Russia quietly withdrew four days later. Much to Austria’s dismay, co-operation with the allies was now her only option due to her own militarily weak nation. Thus on August 14, she agreed to co- occupy the Principalities with Turkey until the end of the war (Baumgart 17). Once again, diplomatic policy generated military action, this time in the form of a Russian retreat.

In his book on the Crimean War, Andrew D. Lambert states “Diplomacy had replaced [military] strategy as the process to secure war aims. The objective remained the same: to prevent Russian expansion on her northern and southern frontiers” (Lambert 328). To some extent, this assessment is true. However, with recent Austrian co-operation, the allies felt the need to specify the exact purpose of their involvement in the war. On August 8, one day after Russian evacuation of the Principalities, France, England, and Austria exchanged letters containing each country’s personal war goals. If Russia failed to accept their collective aims, known as the Four Points, Austria would officially enter the war on behalf of the allies (Baumgart 17). In short, the Four Points were as follows:

1. The Danubian Principalities would be under the guarantee of all the European powers in place of only Russia.Once again, peace seemed within reach. On December 28, 1854, Count Buol of Austria persuaded Russia to accept this ultimatum as a basis of peace talks.

2. The Danube would be a free river.

3. The Turkish Straits would to be free of all warships in the interest of the European balance of power.

4. The Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire would be under the protection of the Porte and not the Russian tsar (Lambert 88).

In spite of the apparent conciliatory nature of these negotiations, each country, for their own selfish reasons, secretly plotted for them to fail. Knowing that Russian would never accept it, France and Britain furtively created a fifth point which elaborated upon the third point in declaring that Russia would have to give up her dominance of the Black Sea by reducing her navy and destroying her key sea port of Sevasopol (Baumgart 19). Both countries would not relinquish their earlier goal of destroying Russia’s militarily. Russia and Austria met secretly as well. At the beginning of January 1855, Austrian emperor Francis Joseph, assured Russian envoy, Prince Alexander M. Gorchvakov that Austria would not agree to the third point which weakened the autonomy of Russia along her Black Sea coast (Baumgart 19). When peace talks open on March 15, they seemed doomed to fail. Yet, contrary to French and British determination to shatter Russia’s military, they proposed a compromise to the third point in which Russian naval forces were to remain fixed at the 1854 status while Turkey and the other Western powers could expand their naval presence to equal numbers (Baumgart 19). Regardless of these concessions, Russian and Austria still refused to sign the Four Points and talks closed on June 4, 1855. Diplomacy failed once more and the fighting continued for six more months.

After the Russian victory over the Turkish fort of Kars in November 26, 1855, Buol presented Russia with a revised version of the Four Points in which the third point was changed from free travel along the Turkish Straits to neutralization of the Black Sea (Baumgart 20). This ultimatum became the foundation of the latest peace talks. After much debate, Paris was agreed upon as the ideal location for these discourses at Russia’s suggestion and thus negotiations for peace began in Paris early in 1856. Russia’s ulterior motive in this selection, however, was to strengthen her ties with France (Royle 470). Napolean was sympathetic to the Russians and their new tsar, Alexander II, but home secretary of England, Lord Palmerstone, vigorously resisted this notion (mars.wnec.edu). France was not willing to sacrifice her newfound relationship with England for Russian amity. Communally, the allies enter the peace talks wanting to deprive Russia of any pretext to intervene in foreign affairs by imposing naval restrictions on her and by placing the Porte under international protection (bartley.com). In the end, the final treaty was only partially satisfied this goal. On March 30, 1856, all parties involved signed the Treaty of Paris whose terms included granting a piece of southern Bessarabia to Moldavia in order to guarantee international navigation of the Danube, insuring the integrity of the Porte, neutralizing the Black Sea, placing Moldavia and Wallachia under Turkish suzerainty, and forbidding Russia to establish troops in Aland, Sweden to prevent her northern expansion (mars.wned.edu). In the words of one Russian historian, the neutralization of the Black Sea “stripped Russia of its fleet and coastal fortifications on the Black Sea. In exchange for the destruction of Kars, the allies returned the Porte city of Sevastopol” (www.neva.ru). In any case, after endless failed attempts, diplomacy had finally ended the war. In April of 1856, the allies began to evacuate Crimea and by July, they were gone (Royle 475).

The diplomatic events of the Crimean

War and the failure of the Concert of Europe had significant impacts on

the future conflicts of Europe during the remainder of the 19th

century. Alexander II, who succeeded Nicholas I in March of 1855,

was inspired by Russia’s defeat to overcome the general backwardness of

Russian foreign and domestic policies in order to compete more effectively

with western European markets and products.He

attracted foreigners to invest in the Russian railroad companies and consequently,

acquired some 30,000 miles of railway that could transport industrial materials

as well as the Russian army more efficiently (Royle, 516).In

addition, both Napoleon III and Alexander II were interested in revising

the 1856 Treaty of Paris, leading to the beginnings of Franco-Russian friendship.Domestic

reform, however, became the main focus of the Russian government.Alexander

II, recognizing serfdom as “‘the indubitable evil of Russian life,’” abolished

the practice in 1861 (Royle 498).Thus

the Crimean War facilitated the industrialization and modernization of

Russia.

Out of all the countries in the Crimean War, Austria probably suffered the most diplomatically.In siding with the allies, she lost all support from Russia and became dependent on France and Britain, both of whom failed to support her in her future clashes with Italy and Prussia.Having lost her powerful foreign support, Austria incurred defeats from Italy in 1859 and from Prussia in 1866.The weakness of the Austria Empire contributed greatly to the unification of Italy and Germany through these defeats.Napoleon III, feeling indebted to Sardinian Prime Minister CamilloBenso di Cavour for his envoy of Italian soldiers during the Crimean War, betrayed his Austrian ally and repaid his debt by supporting the struggling Sardinians in there revolt against Austrian rule in Lombardy and Venetia.In 1866, France again ignored her former Austrian friend.In response to Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismark’s promise of the Alsace-Lorraine territory, France remained neutral in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866.

Overall, the Crimean War had far-reaching consequences. The brief fight destroyed the Concert of Europe which had previously maintained international peace and promoted the balance of power through alliances rather than collective agreements.The failure of diplomacy in the Crimean War contributed greatly to the development of future European conflicts as well to the manner in which they were settled.

Baumgart,

Winfried, The Crimean War 1853-1856. Oxford University Press, Inc.,

London: 1999.

Goldfrank,

David M., The Origins of the Crimean War. Longman Group UK Limited,

New York: 1994.

Henderson,

Gavin Burns, Crimean War Diplomacy and Other Historical Essays.Jackson,

Son & Company, Glascow England: 1947.

Lambert,

Andrew D., The Crimean War: British grand strategy, 1853-56. Manchester

University Press, Manchester: 1990.

Royle, Trevor, Crimea: The Great Crimean War 1854-1856. Little, Brown and Company, London: 1999.

http://mars.wnec.edu/~grempel/courses/russia/lectures/19crimeanwar.html - This site by Professor Gerhard Rempel of West New England College provides wonderful information of the diplomatic prelude, the causes, the events of the war and the results of the 1856 Treaty of Paris.

http://web.ukonline.co.uk/wildbunch/crimea.htm - A brief overview of the Crimean War and its consequences.

http://www.neva.ru/EXPO96/book/chap8-4.html - A Russian site describing all the naval battles of the War and the their consequences.

http://www.bartleby.com/65/ea/EasternQ.html - This site discusses the ‘Eastern Question’ and how this set the stage for the events leading up to the Crimean War.

http://www.batteryb.com/Crimean_War/index2.htm

- An excellent Crimean War site with information concerning the causes

of the war, pre-war conditions, major battles, primary documents from the

war, and bibliographies of important figures of the war. Also, there is

a map of the area around Sevastopol and links to other Crimean War sites.

http://www.dustbunny.fsnet.co.uk/History2.htm - A link describing Italian Unification which discusses the Crimean War’s role in that process.

Site Created by: Nicole

Lesniak