|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By 1952, the American people had grown tired

of bloodshed in the two year stalemate between South Korea, who was backed

by the United States and United Nations, and North Korea, who was backed

by communist China and the Soviet Union. With his emphatic pledge,

“I shall go to Korea,” World War II hero Dwight D. Eisenhower clinched

the American presidency by exploiting confidence that his previous military

experience would allow him to bring the Korean War to a quick and honorable

conclusion. Although an armistice was achieved on July 27, 1953 shortly

after Eisenhower entered office, the apparent peace that was achieved resulted

from factors independent of Eisenhower’s actions. Eisenhower’s bellicose,

militaristic approach could not and would not bring the freedom-promoting,

peaceful result he irrationality thought he would attain.

On June 25, 1950, when North Korean started an invasion across the 38th Parallel that had divided Soviet occupied North Korean and U.S. occupied South Korea since WWII, United States president, Harry Truman, fueled by a popular “containment” policy towards Communism, enlisted the United States in the defense of South Korea. After “Truman’s War” became unpopular and Truman made his highly criticized decision to fire General Douglas Mac Arthur, Truman decided not to run for reelection.

This desperate setting coupled with Eisenhower's

impressive authoritative past would facilitate the legacy of "Ike."

In 1950, Truman himself had contributed to Eisenhower’s noteworthy military

background when he appointed Eisenhower commander of NATO (North Atlantic

Treaty Organization) forces in Europe. General Eisenhower was most

widely known for his service as supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary

Force and mastermind of the infamous Normandy invasion. Additionally,

Eisenhower was the director of the Allied Zones of Occupation immediately

following the war, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, and president of Columbia

University (Medhurst 70-71).

I am not going to give you elaborate generalizations, but hard, tough facts. I am going to state the unvarnished truth.[… I will] re-examine every course of action open to us with one goal in view: to bring the Korean War to an early and honorable end.

[…] I shall go to Korea.

[…] A soldier all my life, I have enlisted in the greatest cause of my life- the cause of peace. (Medhurst 43-44)

With this message of his October 24, 1952 nationally radio broadcasted

campaign speech from Detroit, Michigan, Dwight D. Eisenhower would secure

the 1952 presidential race. Eisenhower got the presidency because

of his pledge to solve the Korean War problem illustrated in newspapers

such as the New York weekly World Telegram and Sun that printed

American casualty lists in huge fonts. There was little that distinguished

Republican candidate Eisenhower from his Democratic opponent Adlai Stevenson

other than the Korean War issue (Leckie 364). Eisenhower did not

disappoint the Republicans that voted him party nominee by a narrow margin

over neo-isolationist Senator Robert Taft when he became extremely popular.

Americans proudly proclaimed "I like Ike" as their faith in the WWII hero

was stimulated by speech writing and oratory skills of Eisenhower's unanticipated

political talent and charisma. Ike’s campaign speeches that he meticulously

personally reviewed every phrase for positive political connotation consisted

of slander against the current Democratic administration:

There is only one issue in this campaign. That issue is – ‘The mess in Washington.’ … There is only one way to get rid of that mess: that is to get rid of the wasters, the bunglers, the incompetents, and the boss politician who have created it. […] no American can stand to one side while his country becomes the prey of fearmongers, quack doctors, and barefaced looters [… so we must] cast away the incompetent, the unfit, the cronies, and the chiseler. (Medhurst 38-39)Ike’s words brought about his landslide 33,936,252 to 27,314,992 victory over Democratic opponent Adlai Stevenson, but his actions did not bring his goals to fruition (Leckie 365). As historian Martin Medhurst reflected on the relationship between Ike’s words and subsequent actions, “It was as though there were two men named Dwight Eisenhower, and the second had no memory or recall of the first” (44).

While

little of the Michigan speech came to be truth after Eisenhower was elected,

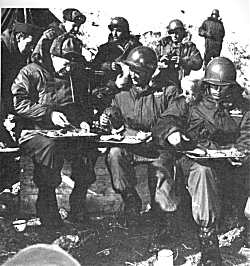

he did keep his promise of going to Korea. On December 2, 1952, the

president elect would make his secret trip to Korea through a series of

long, rough plane and truck rides while decoy personal visited his home

and office. The three day trip consisted of talks with Generals Clark

and Van Fleet, observing front lines and increasing morale for American

and ROK (Republic of Korea) troops, and talks with South Korean President

Syngman Rhee (Leckie 365).

While

little of the Michigan speech came to be truth after Eisenhower was elected,

he did keep his promise of going to Korea. On December 2, 1952, the

president elect would make his secret trip to Korea through a series of

long, rough plane and truck rides while decoy personal visited his home

and office. The three day trip consisted of talks with Generals Clark

and Van Fleet, observing front lines and increasing morale for American

and ROK (Republic of Korea) troops, and talks with South Korean President

Syngman Rhee (Leckie 365).

Eisenhower thought he would “induce peace by deeds,” but his violent deeds were ineffective and counterproductive at producing peace (Leckie 366). Britain’s Winston Churchill told his private secretary that he believed the election of a Republican Eisenhower increased the threat of global war (Hickey 317). Eisenhower advocated the bombing of formerly restricted civilian targets, such as the North Korean capital Yougyang, irrigation dams that protected rice fields, and the Yalu River hydroelectric plants (the primary power source for all Korea). Eisenhower’s attempt to expand his influence by starving the people of North Korea to death put the worst communist atrocities to shame. The Nuremberg Tribunal labeled Ike’s actions as a war crime (Brendon 236). According to now declassified National Security Council minutes, Eisenhower greatly desired to use atomic weapons:

The President seemed not totally satisfied with the argument that atomic weapons could not be used effectively in dislodging the Chinese from their present positions in Korea. […] The President nevertheless thought it might be cheaper, dollar-wise, to use conventional weapons against the dugouts which honeycombed the hills along which the enemy forces were presently deployed. (http://www.dwightdeisenhower.com/koreanwar/144th%20Meeting,%20NSC,%20pg.%2011.gif)The President and his belligerent Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, arrogantly thought that their atomic threat had twisted the arms of the Communists and thereby believed the Reds were pleading for a treaty even though the Truman administration had indicated the same level of atomic threat and had B 29 bombers do obvious test runs with conventional bombs (Matray). Indeed, the Communists showed no sign of being deterred by any of Eisenhower’s actions as indicated by their increased front line aggression right up into the months preceding the armistice.

Eisenhower was not significantly responsible for

the armistice of 1953. The March 1952 death of Josef Stalin was more

much more influential to the signing of the treaty than the election of

Eisenhower. The resulting Soviet power vacuum would not be willing

to expend excess energy on the impasse (Rees 402-403). The Chinese

were experiencing internal economic problems and could not afford continuing

warfare nor did they desire poor relations with the West (Matray).

Ike was not the initiator of truce talks but a cherry picking, passive,

insalubrious author of the armistice, for peace talks had been going on

for almost two years by the time he reached the White House (Gardner 22).

Dwight Eisenhower was a deeply religious man who

imbued spirituality into all extensions of his life. For instance,

he was on a “crusade” against Communism. However, despite its invigoration

by good intentions, Eisenhower’s moral vision failed to open its eyes to

reality. The following statement reveals Eisenhower’s utilitarian

belief that the end justifies the means: “one’s words and actions were

means only: it was the end that counted and that end was understood in

essentially moral and ethical terms” (Medhurst 11). This philosophical

approach was particularly dangerous in a man who was instilled with years

of mindless military discipline that honed his ability to be a “detached,

amoral calculus of the military strategist” (Medhurst 11). He could dismiss

any problems that occurred with his approach because he also believed in

“situationalist” truth (Medhurst 11).

In 1956, historian Richard Revere commented in The Eisenhower Years:

In the three years before we undertook the Korean resistance, Communist power in the world very nearly doubled: in the three years since then, it has made no gains. History will cite Korea […] as the turning point of the world struggle against Communism and as the scene of a great victory for American arms, one the future will celebrate even though the present does not (145).Revere shared Eisenhower’s disillusionment and wishful thinking. They were vehemently reproached by reality. The Korean “turning point” was soon followed by Vietnam, exemplifying American slaughter and embarrassment. Little “celebration” developed for what came to be called “The Forgotten War,” especially in recent times as the base massacre of human life surfaces in the limitless shame of the No Gun Ri affair.

Modern times have witnessed the self annihilation of the communist Soviet Union, but it seems that the oppressive measures the United States has used against Korea, like Cuba, have only served to revitalize and prolong the dying rage of the Red Bruin. North Korea, one of the basely “evil” nations according to President George W. Bush, has turned the tables from 50 years ago so that the United States is now the one who faces the threat of nuclear destruction.

In conclusion, with his emphatic pledge, “I shall go to Korea,” World War II hero Dwight D. Eisenhower clinched the American presidency by exploiting confidence that his previous military experience would allow him to bring the Korean War to a quick and honorable conclusion. Although an armistice was achieved on July 27, 1953 shortly after Eisenhower entered office, the apparent peace that was achieved resulted from factors independent of Eisenhower’s actions. Eisenhower’s bellicose, militaristic approach could not and would not bring the freedom-promoting, peaceful result he irrationality thought he would attain.

Brendon, Piers. Ike: His Life and Times. New York: Harper and Row. 1986.

Gardner, Lloyd C. The Korean War. New York, New York: Quadrangle Books. 1972.

Hickey, Michael. The Korean War: The West Confronts Communism. Albemarle Street, London: John Murray Ltd. 1999.

Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean Conflict. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1999.

Lee, Steven Hugh. The Korean War. London, Great Britain: Pearson Education Limited . 2001.

Leckie, Robert. Conflict: The History of the Korean War, 1950-1953. Toronto, Canada: Longmans Canada Limited. 1962.

Lowe, Peter. The Korean War. London, Great Britain: MacMillan Press, Ltd. 2000.

Medhurst, Martin J. Dwight D. Eisenhower: Strategic Communicator. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1993.

Rees, David. Korea: The Limited. Baltimore, Maryland: Penguin Book Inc. 1964.

Revere, Richard H. The Eisenhower Years. New York: Farrar Straus and Cudahy. 1956

Ridgway, Matthew B. The Korean War. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc. 1967.

Stassen, Harold and Marshall Houts. Eisenhower: Turning the World Toward Peace. St. Paul, MN: Merrill/Magnus Publishing Corporation. 1990.

Matray, James I. "Revisiting Korea: Exposing Myths of the Forgotten War." Korean War Teachers Conference: The Korean War + 50: No Longer Forgotten. 9 February 2001. Truman and Eisenhower Online Libraries. 4 April 2002. <http://www.trumanlibrary.org/korea/matray1.htm>. Matray provides an informative, well researched modern analysis of the Korean War and dispels many of the myths that have emerged about "The Forgotten War."

"Dwight D. Eisenhower: Biography." Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia Online. 2000. Grolier Incorporated. 4 Aprill 2002. <http://gi.grolier.com/presidents/aae/bios/34peise.html>. This site provides a background on Eisenhower's life.

"Primary Resources: The Korean War." Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. 2000. The Dwight D. Eisenhower Foundation. 4 April 2002. <http://www.dwightdeisenhower.com/primarysource.html>. This site provides an excellent plethora of primary resources on Eisenhower and the Korean war including speech transcripts, declassified National Security Council minutes, and pictures.

"End of the Korean War." Eisenhower Birthplace: State Historical Park. 4 April 2002. <http://www.eisenhowerbirthplace.org/legacy/ike0001.htm>. This site provides the picture on the top of this page, a summary of Eisenhower's involvement in the Korean War, and interesting facts including: "Ending the war was also of a personal interest to Eisenhower since John Eisenhower, the President-elect and Mrs. Eisenhower's only living child was serving as an officer in Korea. Casualties for the war totaled some 150,000 Americans, including 34,000 killed in action, 900,000 Chinese, and two million Koreans."

"Happiness and Hostilites in the 1950s." University of South Carolina Aiken. 4 April 2002. <http://www.usca.sc.edu/AEDC442/442984001/HappinessandHostilities.html>. This site is a good image resource and Cold War resource.

Wendel, Marcus. "Korean War Factbook." 4 April 2002. <http://www.skalman.nu/koreanwar/>. This site provides such information as casualties and maps from the Korean War.

"Ike's Korean Shadow." CBS News. 23 June 2000.

CBS Worldwide, Inc. 2 April 2002. <http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2000/06/22/korea/main208505.shtml>.

CBS provides a modern view, history, and interpretation of Eisenhower's

role in the Korean War.

Site Created by: Matthew McCormick