|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The great Italian nationalist warrior, Giuseppe Garibaldi, continually

came to the aid of those fighting for liberation from oppression. Although

sometimes too trusting and prone to exploitation, this altruistic hero

gained support far and wide for his revolutionary causes. He played

integral roles in revolutions in both South America and Italy. This resilient

guerrilla fighter and his band of red shirts were a major component of

the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. By driving out

foreign forces from southern Italy, Garibaldi and his army were as much,

if not more, of a factor than any politician in the eventual success of

the Italian unification.

In the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789, new socio-political ideologies began to emerge as a result of conflict within and between classes. Liberalism, nationalism, socialism, and conservatism evolved from the circumstances surrounding the revolution. Nationalism, in particular, became a dominant force throughout Europe, and this newfound devotion to the concerns and the culture of the nation fueled many of the revolutions that occurred in Europe in the 19th century. Few people embodied this nationalistic spirit more than the Italian freedom fighter, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882). Years of political division and foreign control over Italy led to Garibaldi’s strong desire for liberation and unification of his country. He spent his entire life battling militarily – in his improvisational, guerrilla style – and politically for those who were enslaved and oppressed. He employed the ideal of nationalism to drive himself and his troops. Although he spent nearly ten years of his life devoted to the liberation of the Rio Grande do Sud and Uruguay, he longed to unify his homeland of Italy. His hard-fought efforts in Italy led, for better or worse, to his long desired goal of Italian unification. If not primarily the cause of the success of the Risorgimento, Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was heavily influenced by his time spent in South America, played a pivotal role in the Risorgimento.

Oddly enough, the great champion of the Italian cause was not technically born as an Italian. Garibaldi was born in Nice on July 4, 1807, to Domenico Garibaldi and Rosa Raimondi. At the time, Nice was a part of France, under the control of Napoleon I, but would later be given to Italy by Napoleon in 1815 while he was carving up Europe (Davenport 4). Fortunately for Garibaldi, the spirit of nationalism was already under development during the time of his childhood, for he never would have been able to direct his revolutions without harnessing this power (de Polnay, 1). At the time of his birth, his family did not even own a house. His poverty would help him gain popularity among commoners during the Italian revolution because he could present himself as a man of the people (Hibbert 4). His father was a sailor, and Garibaldi came to know the sea well. When he was only eight years old, he was said to have saved a washerwoman from drowning. His heroic disposition seemed to have emerged early in life (Smith 6). In 1825, he journeyed to Rome with his father, and this month-long stay in the city greatly shaped his later experiences with Rome. In witnessing this bleak Papal Rome, he was convinced that the city had to be freed from its ecclesiastical rule and be made into the capital of a unified Italy.

Garibaldi further developed his personal doctrines and values while

traveling on the sea. During one of his sea voyages, Garibaldi met a group

of Saint-Simonians, who taught him the doctrines of universal brotherhood

and the extinction of classes inherent in the philosophy of Saint-Simon,

an early socialist thinker. He initially empathized with the Saint-Simonians

because they were a persecuted group, but he soon became attracted by their

beliefs (Ridley 24). These doctrines emphasized the importance of a society

whose leadership depended on merit rather than the heredity of classes.

The Saint-Simonians also taught him that a hero is a person who takes on

the problems of another country as his own and offers to fight for this

country (de Polnay 5). Garibaldi told Dumas, the writer of one of Garibaldi’s

autobiographies, how important these teachings were to him:

Strange glimmerings now began to illuminate my mind, by the aid of which I saw a ship, no longer as a vehicle charged with the mission of exchanging the good of one country for those of another, but as a winged messenger bearing the word of the Lord and the sword of the Archangel (de Polnay 5).

The lessons that Garibaldi learned under the Saint-Simonians would

later drive and influence his involvement in the independence movements

in South America.

Before he became engulfed in South American revolutions, he was involved in the rebellion at home. By 1833, when Garibaldi first became involved in Italian revolution, Italy was divided into eight states led by reactionary governments that opposed the recently formed doctrines of nationalism and liberalism (Smith 8). Austria was also a predominate force throughout the Italian peninsula. Late in 1833, Garibaldi met up with the revolutionary secret society, “Young Italy.” The radical Italian, Giuseppe Mazzini, who supported the assassination of despots to precipitate revolutions and wanted a united Italy brought about by revolution, founded this society (Ridley 20). Garibaldi was taken to meet Mazzini and was initiated into the society. Taking a vow to fight against tyranny, injustice, and oppression, Garibaldi pledged for a unified Italy, free from foreign interference. With his still raw spirit of revolution and nationalism, the direction and guidance of Mazzini and the experiences in warfare as a part of Young Italy would later aid Garibaldi in refining and elaborating upon his own doctrines and his own fighting style. However, his first experiences with Young Italy and with revolution were inauspicious. In 1834, he participated in a failed uprising in Genoa, and he had to flee the country. The government in Piedmont condemned all the participants of the insurrection, Garibaldi included, to death for high treason. All Garibaldi was able to accomplish in his first attempt at revolution was to be exiled from the homeland he wished to unite.

Garibaldi still had much to learn about revolutionary politics. He too often jumped into battles without knowing the background of the situation, clinging to naïve beliefs that he was fighting for the cause of liberty and that there was always a right and wrong side to every war or conflict. Those beliefs were evident when he became in a war in South America. Like many Italians trying to escape unemployment, Garibaldi traveled to South America to try to find new wealth and new opportunities. Smith calls Garibaldi’s time in South America the period that “had the greatest formative influence on his character (Smith 11).” Life in South America was hard and cruel. Trust and cooperation were non-existent, and everyone defended his own freedom. During this period in Garibaldi’s life, roughly from 1835 to 1847, the South American way of life was embedded into his personality. He fashioned his dress and fighting style after the Spanish-American gaucho, and he brought these customs back with him when he returned to Italy. After an unsuccessful attempt in the trade industry, Garibaldi joined the battle for independence of the republic of the Rio Grande do Sud against Brazil. Garibaldi still possessed little political knowledge and he did not care about the politics behind the situation. The cause for the fighting was not entirely clear, but because Garibaldi had friends who were involved and because the ideal of liberty was loosely tied to the fight, he plunged headlong into the battle.

Garibaldi

was involved in the fight against Brazil for three years, during which

he was very contented. He was able to do what he loved: fight for an underdog

that had the noble cause, no matter how tenuous it was, of seeking its

freedom. During the fighting, Garibaldi displayed his inflexible, honorable,

righteous character that would gain him so many admirers later in life.

Numerous ships were attacked, but he was never interested in booty. He

was not interested in war for material gain, but to support a just cause.

In battle, the enemies were always more numerous and better supplied, but

this difficulty made the fighting all the more enjoyable for Garibaldi.

He loved being with others who shared his bravery and his zeal for fighting

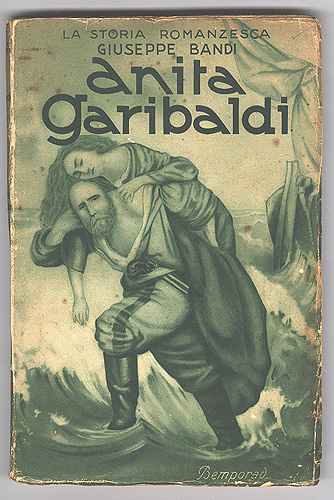

for freedom (Smith 15). In 1839, Garibaldi met his first wife, Anita, a

native of Santa Catarina, a neighboring province of Rio Grande. They were

married in 1842. Her fierce, determined spirit seemed to make her a perfect

match for Garibaldi. Davenport recounts:

Garibaldi

was involved in the fight against Brazil for three years, during which

he was very contented. He was able to do what he loved: fight for an underdog

that had the noble cause, no matter how tenuous it was, of seeking its

freedom. During the fighting, Garibaldi displayed his inflexible, honorable,

righteous character that would gain him so many admirers later in life.

Numerous ships were attacked, but he was never interested in booty. He

was not interested in war for material gain, but to support a just cause.

In battle, the enemies were always more numerous and better supplied, but

this difficulty made the fighting all the more enjoyable for Garibaldi.

He loved being with others who shared his bravery and his zeal for fighting

for freedom (Smith 15). In 1839, Garibaldi met his first wife, Anita, a

native of Santa Catarina, a neighboring province of Rio Grande. They were

married in 1842. Her fierce, determined spirit seemed to make her a perfect

match for Garibaldi. Davenport recounts:

Garibaldi’s honeymoon with Anita began with a battle in which Imperial forces bombarded his ship from close range. A cannon ball landing near by knocked Anita unconscious. She fell on top of a pile of dead men. By the time Garibaldi reached her side, she was on her feet, in action again (Davenport 20).

Anita’s homeland, Santa Catarina, felt that the Rio Grande, who

had liberated them from Brazilian rule, was ruling too violently and Santa

Catarina rebelled against the Rio Grande. At this point, the Rio Grande

dropped its liberalism and Garibaldi was ordered to attack one of the rebel

cities. Garibaldi was disillusioned by the harshness of the attack and

the reckless actions that his men displayed during the attack. The war

had lost its focus, if it ever had one in the first place, and neither

the natives nor the soldiers knew for what they were fighting. Garibaldi

was further disheartened as it became increasingly clear that selfish personal

interests instead of liberty were at issue in the war. In 1840, growing

disgust with the nature of the war and a series of Brazilian victories

caused Garibaldi to leave the Rio Grande. Garibaldi learned a hard lesson

in the Rio Grande about how distorted the nature and causes of war can

be (Smith 18).

Despite this newly learned lesson, it only took him a year to become involved in another South American war in which the motives were not well defined. This time, he was fighting for what he thought were liberty and humanity in supporting Montevideo, Uruguay, against General Rosas, who governed nearby Argentina. Uruguay had recently declared independence from Argentina, but in the name of liberty, Oribe had already ousted the first president of Uruguay, Rivera. Basically, the war was an internal faction fight. General Rosas of Argentina backed Oribe and Garibaldi joined the underdog, Rivera. In 1842, Garibaldi was charged with the difficult task of linking the Uruguayan navy with Unitarian allies in Corrientes. This voyage would require Garibaldi and the navy to travel 600 miles through areas heavily occupied by the Argentine fleet (Ridley 111). In August of 1842, his forces were finally trapped and he was forced to burn his ships and make an escape. A few months following this defeat, Oribe prevailed over the main army of Rivera. Once again, Garibaldi watched as private aspirations and faction disputes played a role in the defeat of the cause of liberty for which he had been fighting. Garibaldi was losing faith in and growing suspicious of politicians (Hibbert 23). He began to seek more control over his operations with less interference from the government.

In 1843, Uruguay renewed its war with Argentina and Garibaldi was able to gain the control that he sought over the war against Argentina when he took command of the Italian Legion, a group of Italian patriots “fighting for the liberty of the country which had given them a home (Davenport 24).” Although the legion only consisted of a few hundred members, it had a number of positive features. The legion had a strong sense of Italian nationalism, and Garibaldi gained valuable leadership experience by commanding it. He was able to fix some of the organization and disciplinary problems that he had previously encountered, noticing that he needed to become more astute and crafty. In his time with the Italian Legion, Garibaldi developed the guerrilla techniques that he would employ in nearly all of the rest of his battles. He believed strongly in courage and the ability to be able to improvise and make quick decisions on the battlefield. With such a large number of untrained fighters under his command, Garibaldi noticed that morale was all-important. The best way to maintain morale, he thought, was to win and get his troops to believe that they would always win. To ensure victory, he always tried to keep the initiative in battle, and he sought to surprise the enemy. He was known to shoot deserters in order to stop a general panic from ensuing, believing that individual lives are nothing in the pursuit of a noble cause (Smith 23).

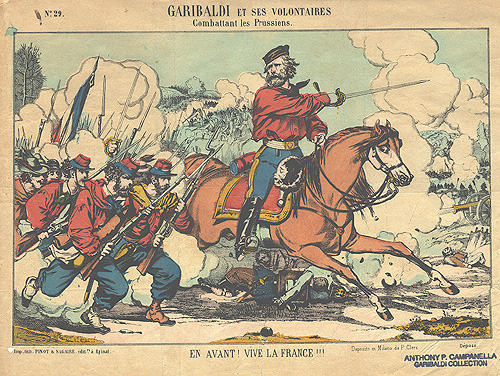

Garibaldi and his guerrilla-fighting countrymen first donned their famous red shirts in Montevideo. Although red was the color of revolution, they most likely wore the red shirts because they intercepted a shipment of clothing on its way to a slaughterhouse in Buenos Aires. These red shirts, initially meant to hide the blood of cattle, would soon be needed to conceal the slaughter of countless battles (Davenport 24). Throughout these bloody battles, Garibaldi and his troops continued to fight for Montevidean liberty without corrupting themselves. They avoided plundering their foes and they turned down the numerous gifts offered to them by happy, yet corrupt statesmen (Hibbert 23). Smith states, “it was a point of pride and dogma that they were not fighting for material rewards, but stood for patriotism and humanity against the imperial tyranny of Argentina (Smith 25).”

Ultimately, however, the Montevidean government was not as noble as Garibaldi’s legion. By 1845, the army of Argentina was laying siege to Montevideo, and personal interests had created internal divisions in the government. Rivera was exiled, and France and Britain stepped in to defend their interests in the maintenance of the independence of Uruguay. Along with French and British navies, Garibaldi and his men ended the siege and pushed back the enemy. Hundreds of hard-fought battles ensued and Garibaldi’s men faced harsh conditions, living on horseflesh. In 1846, a coup d’etat stopped all parliamentary proceedings, and the exiled Rivera was brought back to power. Garibaldi acted in a more restrained manner because he sensed that the war had strayed from a goal of liberty (Smith 27). He had to petition the government just to get food and supplies for his troops. The growing governmental interference with his troops and the fighting caused Garibaldi’s disdain for politics to increase. In 1847, he witnessed the corrupt Rivera once again fall in defeat to Argentina. Diplomats now guided the war to an anticlimactic ending by negotiating a compromise peace between Uruguay and Argentina. The native members of the army of Uruguay were growing more hostile to the foreign Italian Legion. Garibaldi and his troops were disillusioned by the selfish attitudes of the town diplomats and inhabitants and the number of Italian Legion troops diminished (Hibbert 23). Garibaldi turned his attention elsewhere, where he would be needed and welcomed.

Italy was

one such place that needed his attention. In April 1848, Garibaldi and

60 members of the Italian Legion set sail for Nice to partake in the Risorgimento

(Smith 31). King Charles Albert of Piedmont had just declared war on Austria,

and Garibaldi wanted to enlist under the King’s army. He was turned away,

however because politicians of Piedmont feared his radicalism and the army

generals looked down on his unconventional military training. As Garibaldi’s

bid was rejected, radicals and patriots began to question the King’s motives

for getting involved in the war. Some felt that he was more interested

in enlarging his kingdom of Piedmont than he was in promoting Italian patriotism

and unity. Still looking to get involved in the Italian cause, Garibaldi

joined the army at Milan, where he was appointed general. Finally with

a chance to fight for his country, Garibaldi proclaimed, '“liberation of

one’s country from the foreigner is the most beautiful, the most sublime

thing possible (Smith 32).”' After only a week of fighting, the King’s

army, lacking unity and leadership, was defeated at Custoza and Piedmont

withdrew from the war (Davenport 41). Disappointed with the King’s efforts,

Garibaldi defied the King’s orders to demobilize his army, and for nearly

12 days, Garibaldi and 750 loyal men carried on the war (Hibbert 32). Although

his efforts turned out to be futile, he found out that his South American

guerrilla tactics could work in Italy and as his number of troops dwindled,

he saw that Italian commoners were more reluctant to fight for the cause

of nationalism than he once thought. Because of his low number of troops,

he was forced to make an escape into Switzerland.

Italy was

one such place that needed his attention. In April 1848, Garibaldi and

60 members of the Italian Legion set sail for Nice to partake in the Risorgimento

(Smith 31). King Charles Albert of Piedmont had just declared war on Austria,

and Garibaldi wanted to enlist under the King’s army. He was turned away,

however because politicians of Piedmont feared his radicalism and the army

generals looked down on his unconventional military training. As Garibaldi’s

bid was rejected, radicals and patriots began to question the King’s motives

for getting involved in the war. Some felt that he was more interested

in enlarging his kingdom of Piedmont than he was in promoting Italian patriotism

and unity. Still looking to get involved in the Italian cause, Garibaldi

joined the army at Milan, where he was appointed general. Finally with

a chance to fight for his country, Garibaldi proclaimed, '“liberation of

one’s country from the foreigner is the most beautiful, the most sublime

thing possible (Smith 32).”' After only a week of fighting, the King’s

army, lacking unity and leadership, was defeated at Custoza and Piedmont

withdrew from the war (Davenport 41). Disappointed with the King’s efforts,

Garibaldi defied the King’s orders to demobilize his army, and for nearly

12 days, Garibaldi and 750 loyal men carried on the war (Hibbert 32). Although

his efforts turned out to be futile, he found out that his South American

guerrilla tactics could work in Italy and as his number of troops dwindled,

he saw that Italian commoners were more reluctant to fight for the cause

of nationalism than he once thought. Because of his low number of troops,

he was forced to make an escape into Switzerland.

Despite the disobedience he showed toward King Charles Albert, Garibaldi was allowed back into Nice, whose representative government was based in Turin, after his failed attempt at revolution. Garibaldi did not remain inactive for long. He tried to rally support for revolutions in Sicily and then Tuscany, both to no avail. Determined to fight somewhere, Garibaldi took up the cause of Venice against Austria. But in 1848, on his trek to Venice, he heard about the assassination of Count Rossi, the Pope’s Conservative minister, which caused the Pope to flee to Naples (Ridley 20). Sensing an opportunity to fuel a revolution, Garibaldi and his troops marched into Rome, where Garibaldi was granted the position of colonel in the defense of the new Roman republic. In 1849, he was elected to the Roman assembly, but he was ill suited to participate in the parliament. He was annoyed by the lack of action behind all of the talk in the assembly.

Finally, in April, emperor Louis Napoleon sent his French troops to Rome to restore the Pope and Garibaldi was called to action to defend the republic. The French were repelled initially, and a period of inactivity set in. The French did not seriously commit to the war until June 3, 1849, devoting 60,000 troops and additional resources to the battle (Smith 41). Garibaldi and the other defenders of Rome were outnumbered and undersupplied. But what the troops lacked in equipment and experience, they made up for in bravery and heroism. Garibaldi did an admirable job of motivating his ragged, unskilled band of men. For 27 days, his troops were able to defend Rome against the heavy artillery of the French (Davenport 80). But a large number of his best soldiers were killed, and on June 30, Garibaldi was called to the Capitol. When asked his opinion about the status of Rome, he admitted that he did not believe that a defense of the republic was possible any longer (de Polnay 70).

The assembly, acknowledging defeat, gave Garibaldi permission to do whatever he deemed necessary to keep revolution alive in Italy. Accompanied by about 5,000 men, he set off on his journey out of Rome, still looking to fight the forces of Italian oppression (de Polnay 70). On his trek out of Rome, the French, Neapolitan, Austrian, and Spanish armies laid in waiting. Local villagers were reluctant to join Garibaldi’s hapless and seemingly hopeless cause. Because Garibaldi could no longer guarantee frequent victories, troop morale dropped and desertions were frequent. On July 30, realizing that his cause was, at the moment, futile, Garibaldi dissolved his army and sought temporary refuge in neutral San Marino. Continuing his flight through Austrian lines, Garibaldi’s wife, Anita, who had fought alongside her husband throughout their retreat from Rome, died before Giuseppe could reach safety in a ship off the Tuscany coast. Unhappy with Garibaldi’s participation in the revolution in Rome, the conservative government in Turin, Piedmont, wanted to get Garibaldi out of Italy. Fearing that the now popular Garibaldi would be elected in an upcoming parliamentary election, the parliament had Garibaldi arrested and shipped off to Tangier (Smith 48).

Although the Roman republic was defeated, Garibaldi’s efforts were not fruitless. The fierce battle that occurred over Rome caused Europe to realize that Rome should at some point become a part of Italy (Smith 42). The defense of Rome also greatly enhanced Garibaldi’s publicity. People around the world began to recognize and admire Garibaldi’s altruistic fight against oppression. Along with Garibaldi, Italian nationalism grew more popular in England. Garibaldi was quickly becoming a national hero and as time carried on, his popularity only increased (de Polnay 79).

His popularity may have been on the rise internationally, but at home, his popularity among the conservative governments of Italy was wearing thin. After fighting for nationalism and liberty for more than 12 years, Garibaldi found himself inactive in revolutions during his exile. From 1849 to 1854, he was mainly occupied with fishing and sailing. He spent a few months in the United States during this time and got his first taste of democracy. The liberty that existed in the United States as well as in Great Britain greatly impressed Garibaldi, and he dreamed of developing a sort of United States of European nations based on a foundation of universal peace and brotherhood (Smith 66). Although Garibaldi had a fervent love for Italian liberty and nationalism, he was just as passionate about his love of humanity. While he was developing these ideals overseas, he was able to gain enough money to attempt to return to his family in Nice.

To return home, Garibaldi knew that he must not appear to be a threat to stir up a revolution in Italy, and must therefore not be viewed as a problem by the government of his homeland based in Piedmont. By 1854, King Victor Emmanuel ruled over Piedmont and Count Cavour was the aristocratic, moderate liberal prime minister of the kingdom. Cavour strongly opposed revolution and held Mazzini as his enemy. He was hesitant at first to let the volatile Garibaldi back into the country, but once it appeared that Garibaldi had no intention of causing problems in Sicily, and after political tensions had receded, Garibaldi was allowed to return to Nice with his family (Davenport 108). Garibaldi was satisfied with waiting to see how Cavour would handle unification, and he settled on the nearby island of Caprera (Smith 54). Here, he spent much of his time farming, living a simple, laborious existence, and receiving mail from those who admired and supported his cause of Italian nationalism. Until 1859, Garibaldi spent most of his time on Caprera and out of battle.

He did not, however, remain out of politics during the stay on his island. In 1856, Cavour began his plan for the unification of northern Italy at the expense of Austria. Cavour’s strategy to accomplish this unification was to enlist the aid of the French emperor Louis Napoleon to gain back the territories of Venice and France in exchange for the French-bordering territories of Nice and Savoy. Cavour also needed a stronger Piedmontese army to complement the French troops. The clever politician knew that to raise an army, he would need a person to rally around, and Garibaldi fit the mold perfectly. Garibaldi met with Cavour and the King in 1856 and in 1858, when Cavour divulged details on the upcoming war that he was trying to provoke, requesting Garibaldi’s cooperation (Smith 70). Cavour planned on finding some excuse for war with Austria where 200,000 French and 100,000 Piedmontese troops would be deployed to march into Lombardy and cast out the Austrians (Hibbert 142). The possibility of a war to fight for any sort of Italian unity excited Garibaldi, and he immediately put his faith in the Piedmontese government. Garibaldi believed that Piedmont would be better served with a military dictatorship because he thought the discussions and arguments that emerged from the parliament were useless and counterproductive. Cavour, instead, wanted to band together with the radical democrats in the parliament to give himself and parliament more power while weakening the force of revolutionaries (Smith 72). He, likewise, did not want to give the liberal Garibaldi too much power, so Garibaldi was given a complementary role instead of a primary role in the war (Hibbert 148).

In 1859, just before the war began, Garibaldi was appointed a major general in the Piedmontese army. He was to command the volunteer brigade, and he immediately started recruiting, eventually drawing around 3,000 loyal men (Davenport 116). Many of the men who joined this brigade had previously served under Garibaldi in Rome. Like most of the troops that he had previously led, the volunteers were untrained individuals. Some were students who were caught up in the spirit of nationalism and fighting for a noble cause. Just as when he led the red shirts, he believed that enthusiasm and confidence were more important in battle than military training. He placed importance on attaining success in battle, and his unwavering confidence in himself and his battle tactics became contagious among his men, who already loved him and considered him a legend.

With his troops intact, Garibaldi first planned to go into Lombardy and try to convince the people to rise up in rebellion against the Austrians. He intended to gain the support of the Lombards against the Austrians by eliminating heavy food taxes and by stirring up the spirit of Italian nationalism. The government at Turin, however, did not look favorably upon Garibaldi’s plan of revolution in Lombardy. Turin was aware that not all Italians were filled with a desire to fight for their country, and many of the Lombards were already in the Austrian army. Compounding these problems was the fact that Austrian spies, who could give away the military’s positions, were also prevalent throughout Lombard villages (Smith 74). These complications ultimately forced Garibaldi to desert his plans of revolution.

Instead of riling up a revolution in Lombardy, Garibaldi and his volunteer division were ordered to create a diversion on the enemy’s extreme left flank, while the main force of 60,000 Italians and 120,000 French confronted the Austrian army (Smith 75). Garibaldi’s duties in the war were to drive on the Austrian armies that the French and Piedmontese armies had defeated and to liberate the northernmost Lombard towns from their foreign occupants (Davenport 118). Setting out in April, his unit moved stealthily and quickly, and Garibaldi attempted to increase upon his sparse number of troops by trying to arouse a sense of nationalism in northern Italians. Despite having a lower number of troops and supplies than he had been promised, Garibaldi was able to score a victory at Varese. While Garibaldi’s division was engaging in small battles, the main force defeated the Austrians at Palestro on May 31 and Magenta on June 4 (Smith 75). Although Garibaldi was optimistic about these early victories, the accomplished war hero was unhappy that he was placed in charge of a poorly equipped and staffed campaign that fought in relatively insignificant battles. To add insult to injury, Garibaldi was called back to Milan shortly after the battle at Magenta, and his company was merged into the main force. While Garibaldi’s military autonomy was being stripped, the Italian and French armies lost contact with the Austrians. This lack of initiative gave the enemy a chance to regain strength. On June 24, 1859, the opposing armies (Garibaldi’s forces were still too far away to partake in this battle) met at Solferino in an intense battle in which no clear victor emerged (Davenport 122). Louis Napoleon was soured on the war after this battle, and the French reached an agreement with Austria in the armistice of Villafranca. An enraged Cavour watched King Victor Emmanuel accept the terms of the armistice, which only gave Italy Lombardy.

Discord was growing between Cavour and Victor Emmanuel in Piedmont. Cavour was disappointed in the King for signing the armistice, and the King was wary of the manipulative Cavour trying to control him through parliament (Smith 83). The King, on the other hand, admired Garibaldi for his loyalty and forthrightness. In December, Victor Emmanuel called Garibaldi for a meeting where he spoke severely of Cavour, with whom Garibaldi also had personal differences. From this meeting, Garibaldi gained a sense that he could trust the King. In spite of Cavour’s early attempts to limit Garibaldi’s popularity and power in the war of 1859, Garibaldi had not completely lost faith in him. Garibaldi still clung to the hope that Cavour would focus more on the concerns of an Italian nation than on the concerns of Piedmont alone (Smith 87). These hopes were dashed when Cavour negotiated a secret deal with Louis Napoleon to give France the Italian territories of Nice and Savoy in exchange for future assistance in war. Garibaldi was enraged that his birthplace, Nice, had been given to the man he had battled against in 1849 in Rome. As a result of Cavour’s arrangement, Garibaldi’s relationships with Cavour and with the Turin parliament, which he viewed as increasingly corrupt, were forever strained (Smith 89).

By 1860, Garibaldi, facing the loss of Nice and Savoy, was bent on unifying Italy. Even though Cavour had failed in obtaining Venice from Austria, most of northern Italy was unified. Piedmont, Sardinia, Lombardy, Tuscany, Tuscany, the central duchies, and a portion of the Papal States were united in a virtual kingdom (Smith 90). Southern Italy, mainly comprised of Naples, Sicily, and Rome were still under foreign control, however. Garibaldi was willing to help these southern territories revolt if they were ready. Mazzini’s followers tried to encourage Garibaldi to get involved in the south by stirring up revolutions. In the meantime, Garibaldi appealed to old friends and supporters of the Italian revolution and unification efforts for money to fuel the revolution. In anticipation of revolution, volunteers assembled in Genoa. Almost half of the 1,089 volunteers, also known as the “Thousand,” were under the age of 20 (Smith 92). The Thousand was composed of students, unemployed workers, refugees, but mostly romantic patriots. Finally, on May 5, 1960, Garibaldi and the Thousand, some of whom wore red shirts, set sail to rile up a revolution in South America. Garibaldi’s expedition had no predetermined destination. He searched for areas where revolutions were actively occurring, and he found such an area in Sicily.

Garibaldi was not popular everywhere he went in Sicily. Upon his landing, he proclaimed himself a dictator in the name of Victor Emmanuel, whom he felt should lead a unified Italy, and he requested food, money, and men for the army from the local populace. By eliminating pasta and salt taxes and promising to redistribute land, Garibaldi was able to gain support and popularity among the Sicilians, some of whom joined his army. The Bourbon King of Naples looked to crush this uprising before it could gain momentum, sending 3,000 troops to put down the rebellion (Smith 95). The two armies engaged in a disorganized battle at Calatafimi. Garibaldi’s men fought courageously and with abandon, and by sheer will, the revolution gained its first victory. The success of the first battle gave the revolution a sense of legitimacy and it encouraged more Sicilians to join Garibaldi’s cause. Now, Sicilians were inspired by nationalism to take up arms against Bourbon troops.

With victory

under their belts, Garibaldi’s troops fought a number of small, surprise-attack

battles before reaching Palermo, the Bourbon stronghold. Garibaldi had

only about 3,000 men to attack a city that held 20,000 enemy troops (Smith

96). With the odds stacked against him, Garibaldi used mock campfires to

lure many of the troops away from the city, and with the enemy’s corps

depleted and not expecting attack, he moved his troops into Palermo. After

a few hours of street fighting, Garibaldi held much of the city. Garibaldi’s

success compelled the oppressed city dwellers to build barricades, and

once again, Garibaldi’s troops had scored an unlikely victory. Following

Garibaldi’s victory at Palermo, the Bourbon’s signed an armistice that

allowed them to safely depart to Naples. Garibaldi did not want to lose

any momentum and wanted to carry the spirited revolution across the Strait

of Messina into Naples with as little interference as possible from the

Turin government. The cabinet at Turin, fearing that further movement would

cause a dispute with France, tried to prevent him from making the journey

into Naples, but King Victor Emmanuel secretly supported Garibaldi in his

quest. If Garibaldi could take Naples, the King could reap the benefits

of controlling a unified Italy. If Garibaldi failed, the King could claim

that Garibaldi was acting on his own.

With victory

under their belts, Garibaldi’s troops fought a number of small, surprise-attack

battles before reaching Palermo, the Bourbon stronghold. Garibaldi had

only about 3,000 men to attack a city that held 20,000 enemy troops (Smith

96). With the odds stacked against him, Garibaldi used mock campfires to

lure many of the troops away from the city, and with the enemy’s corps

depleted and not expecting attack, he moved his troops into Palermo. After

a few hours of street fighting, Garibaldi held much of the city. Garibaldi’s

success compelled the oppressed city dwellers to build barricades, and

once again, Garibaldi’s troops had scored an unlikely victory. Following

Garibaldi’s victory at Palermo, the Bourbon’s signed an armistice that

allowed them to safely depart to Naples. Garibaldi did not want to lose

any momentum and wanted to carry the spirited revolution across the Strait

of Messina into Naples with as little interference as possible from the

Turin government. The cabinet at Turin, fearing that further movement would

cause a dispute with France, tried to prevent him from making the journey

into Naples, but King Victor Emmanuel secretly supported Garibaldi in his

quest. If Garibaldi could take Naples, the King could reap the benefits

of controlling a unified Italy. If Garibaldi failed, the King could claim

that Garibaldi was acting on his own.

The strong Neapolitan fleet, occupying the Strait of Messina, stood in the way of Garibaldi’s progress into Naples. Because of his successes in Sicily, by July 30, Garibaldi’s forces had increased to approximately 10,000 to 15,000 men (Smith 102). But, to make his way across the Strait of Messina, he had to take significantly fewer men. He planned to land in Calabria in the town of Reggio. On August 18, Garibaldi, accompanied by about 3,500 soldiers, quickly crossed the strait into Calabria under cover of night (Smith 103). He set up his forces in the hills of Reggio, and from there, he opened up a barrage on the 16,000 enemy troops anchored in Calabria (Smith 103). Within two days, the enemy was defeated, and the remainder of Garibaldi’s troops crossed over to Calabria for a charge up the boot of Italy. The enemy troops were panicked by Garibaldi’s victories, and, by August, over half of the enemies had surrendered, many willingly.

Garibaldi now learned that Cavour was planning to stage his own coup in Naples, in part to impede the progress of the revolution from reaching Rome. Garibaldi pushed even harder to reach Naples so he could establish himself there before Cavour. Garibaldi could then use Naples as a jumping point to carry the revolution on to Rome. As Garibaldi’s forces approached Naples, the Bourbon King Francis fled by sea. On September 7, Garibaldi, having split off from his army, accompanied by only a half dozen men entered Naples. The half million inhabitants of Naples met Garibaldi with incredible support, cheering him through the streets (Davenport 170). The Bourbon troops still occupied the fortresses in the city, but no shots were fired. Instead, most of them retreated to Rome, and Garibaldi became the dictator of Naples. During his two months as dictator, Garibaldi attempted to establish free education, and, having witnessed clerical monopolies and privileges in Southern Italy, he disbanded the local Jesuits and nationalized their property. Garibaldi’s main concern in Naples was to formulate a plan to take Rome and the Papal States.

Cavour intervened before Garibaldi could execute a march on Rome. To keep the French on his side and to stop Garibaldi’s revolution, Cavour invaded the Papal States, bypassing Rome. He succeeded in bringing the Papal States into the newly unified Italy without angering the large Catholic population in France. While the army of Victor Emmanuel was crushing the weakened forces in the Papal States, Garibaldi moved his men north to the Volturno River. Here, he encountered more than 50,000 Bourbon troops intent on regaining Naples (Davenport 172). Contrary to Garibaldi’s other battles, the battle at Volturno River was long and Garibaldi was on the defensive. He had to adjust his guerilla fighting tactics to successfully defend Naples. Despite having only 21,000 men, his army was able to hold out against the Bourbon enemy and Naples was safe (Davenport 172). On October 26, Victor Emmanuel rode into Garibaldi’s camp. The two shook hands, and the King informed Garibaldi that the Piedmontese army would take over military operations. Garibaldi would then transfer his power as dictator of Naples and Sicily to Victor Emmanuel, who controlled northern Italy. Thus, Victor Emmanuel became the first king of a united Italy (with the exceptions of Rome and Venice).

Garibaldi returned to farming at his island in Caprera. He would subsequently fail on two attacks on Rome. In his later years, he remained active in his fight against oppression. He advocated policies of emancipation, suffrage, and women’s rights and promoted the abolishment of capital punishment. He remained popular throughout much of the world for his works of liberation and revolution, and he had celebrity status in America and England. He was a model for all those who felt oppressed and served as inspiration for those battling for freedom and nationalism. Prussian victories against Austria in 1866 and France in 1870 allowed Italy to gain Venice and Rome and Garibaldi’s vision of a unified Italy was fully realized.

Garibaldi will always be remembered for his early years of fighting in South America and the major role that he played in the unification of Italy. Many commoners could identify with him because of his humble beginnings and because of his love for liberty and humanity. His selfless, honest, and loyal personality also gained him many devoted troops and admirers throughout his life. He often blindly leapt into battle, needing only the vaguest notion of liberty or nationalism to fuel his attention. The years that he spent in South America helped develop his leadership skills and his guerrilla fighting techniques. Although happy to be battling oppression in South America, he was at his peak when fighting for the unity of his homeland. His ability to motivate Italians to fight for their country was a useful tool for Cavour and Victor Emmanuel to unify Northern Italy. But Garibaldi’s crowning achievement was the march that he and his band of red shirts made through southern Italy. His victories caused the long suppressed nationalist spirit of the southern Italians to break free. He fought bravely and exhaustively for his country and succeeded in expelling foreign influence from southern Italy. Without his efforts, southern Italy may never have become integrated into King Victor Emmanuel’s northern Italian kingdom, and Italy might have never become unified. Giuseppe Garibaldi was truly a champion of the people.

Unfortunately, the social and educational reforms Garibaldi introduced to southern Italy were abolished and northern Italy would come to rule over southern Italy as if it were a conquered nation. The urban north contrasted heavily with the agrarian south. Poor southern peasants protested the heavy taxation the north imposed upon them. Because of these protests, socialist representatives became more numerous in Italy’s government, giving the people a more prominent voice in the government. As a result of greater mass participation in government, the Italian government could become more internally unified. In 1913, this newly strengthened government made progress in social reforms with the establishment of universal suffrage (Albertini). Today, Victor Emmanuel’s dynasty is no more, and Italy exists as a republic. It still remains unified, thanks to the efforts of Garibaldi, and Garibaldi’s name is held in the heart of every Italian.

Albertini, R. "The Problem of Southern Italy." Windows on Italy. Instituto Geografico De Agostini. 14 April 2002 <http://www.mi.cnr.it/WOI/deagosti/history/today.html#The%20Problem%20of%20Southern%20Italy>

Davenport, Marcia. Garibaldi: Father of Modern Italy. New York: Random House, 1957.

de Polnay, Peter. Garibaldi: The Legend and the Man. London: Hollis & Carter, 1960.

Hibbert, Christopher. Garibaldi and his Enemies: The Clash of Arms and Personalities in the Making of Italy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1966.

Ridley, Jasper. Garibaldi. New York: The Viking Press, 1976.

Smith, Dennis Mack. Garibaldi: A Great Life in Brief. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1970.

http://www.sc.edu/library/spcoll/hist/garib/garib.html This site contains brief bits of biography on Garibaldi accompanied by items from the Anthony P. Campanella Collection of Giuseppe Garibaldi.

http://www.ohiou.edu/~Chastain/dh/gari.htm This site has a short description of Garibaldi and his exploits prior to Rome in 1849.

http://www.reformation.org/garibaldi.html A biography of Garibaldi's entire life and a unique viewpoint on the Vatican City State can be found here.

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1860garibaldi.html An account of Garibaldi's conquest of Naples can be found on this site.

http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/moa/pageviewer?frames=1&coll=moa&view=50&root=%2Fmoa%2Fcent%2Fcent0024%2F&tif=00515.TIF&cite=http%3A%2F%2Fcdl.library.cornell.edu%2Fcgi-bin%2Fmoa%2Fmoa-cgi%3Fnotisid%3DABP2287-0024-146

Passages from The Personal History of Garibaldi are displayed here.

Site Created by: Jon Thompson