|

Hollywood’s Role in World War II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior to World War Two, films were created for entertainment not as propaganda tools. Movies were produced in Hollywood, CA, but their influence did not stop there. The film industry’s reach expanded to touch all of the United States and eventually the movies were enjoyed by several European nations, including Germany. In the early 1930’s, Germany was a profitable market for Hollywood’s films. Likewise, prominent German director Leni Riefenstahl and her productions were well known among the film community. Ms. Riefenstahl was considered to be a brilliant director and could be seen socializing among Hollywood’s elite circles. In November of 1938, Riefenstahl even toured the United States with her film Olympia, hoping to release it for public consumption. However, it was then that Ms. Riefenstahl’s associations with the Nazi party prevented her from sweeping the nation with her talent. America closed its doors to the reputed “director of the Third Reich” and the only parts of her German films that the public saw were scenes spliced into newsreels and war orientation films. As the decade came to a close, Germany once again became embroiled in political conflict. American movies and entertainment slowly stopped being imported and the cultural exchange was severed.

Soon after Europe became isolated from America’s media influence, Hollywood began producing more opinionated pictures. In fact, the film industry began taking sides long before the United States government had declared war. In 1939, Warner Brothers produced Confessions of a Nazi Spy. The movie was one of the first obvious blows to Germany and its Nazi ideals. For some government officials, the film posed a political threat, since America was still asserting a neutral stance. With the release of The Great Dictator in 1940, Hollywood was starting to become more radical in expressing its anti-Nazi beliefs. State and studio cooperation informally began on June 5, 1940, when film industry leaders joined to form the Motion Picture Committee Cooperating for National Defense. The union spurred studios to produce 25 defense related films and 12 trailers for Army recruitment. (Doherty, 39) That committee was later expanded in Hollywood and renamed the War Activities Committee of the Motion Picture Industry (WAC).

In September of 1941, two months prior to America’s entry into the war,

Hollywood’s anti-Nazi position was challenged by Senator Gerald Nye, an

isolationist and anti-Semite. Nye accused producers, who were often of

foreign descent, of being more concerned with their homeland than the American

home front. Nye blacklisted several films, including Confessions of

a Nazi Spy and The Great Dictator. The Motion Picture Producers

and Distributors of America hired former presidential candidate Wendell

Willkie to fight for Hollywood. Renowned producer Darryl Zanuck also spoke

in favor of the film industry:

I look back and recall picture after picture, pictures so strong and powerful that they sold the American way of life not only to America but to the world. They sold it so strongly that when dictators took over Italy and Germany, what did Hitler and his flunky, Mussolini, do? The first thing they did was ban our pictures, throw us out (Doherty, 41).

Zanuck’s speech disintegrated Nye’s complaint and the Senate erupted

into applause and the court was adjourned.

However, it was not long before Hollywood could freely express its disdain for Nazi activity. On December 18, 1941, President Roosevelt formally called Hollywood to help with the war effort. Lowell Mellet was appointed as Coordinator of Government Films and several verbal agreements between state and studio were established. Hollywood was to clarify the Lend-Lease Program and promote a decline in pleasure spending, an increase in War Bond purchases, and payment of taxes to counteract inflation. The government and Hollywood had entered World War II hand in hand.

Hollywood

was an essential part in creating a positive war mentality where isolationist

fears once blocked America from helping Allied Europe. By the end of the

thirties, the American movie industry was the fourteenth largest business

in the country. Some members of this elite group were the stars of the

silver screen. With their talent and fame, they held a lot of influence

over the enamored public. Actors and actresses were the ones most responsible

for drumming up public acceptance of the war, since they were the most

visible members of the film community. The enthusiastic performers legitimized

the cause and defined the purpose of the war. They continued to boost home-front

morale and increase public support throughout the forties. At the beginning

of World War II, many citizens were reluctant to leave their safe and stable

lives to join the Armed Forces, but men were soon lined up to volunteer

their services to the government. Actors like James Stewart, Clark Gable,

and Ronald Reagan set a national example when they enlisted. Jimmy Stewart,

who had joined the Army Air Force Corps as a private, eventually advanced

to the position of lieutenant colonel. Later, after receiving the Air Medal

and the Distinguished Flying Cross award for his service in the United

States Air Force, Jimmy Stewart became a brigadier general in the Air Force

Reserve. Actor Audie L. Murphy also defended his country on the battlefields.

Murphy, who was a Staff Sergeant, became the most decorated soldier in

the history of World War II. For defeating an entire enemy infantry by

himself, Murphy was awarded with the Congressional Medal of Honor as well

as every other military honor available. In several cases, Hollywood stars

not only joined the army, but succeeded to the point of national recognition.

Their enlistments were not merely publicity stunts. According to Otto Friedrich,

the author of the book City of Nets, by October of 1942, more than

2,700 members of the Hollywood film industry had joined the Armed Forces

(Friedrich, 106) . At least one-fourth of the male employees at Warner

Brothers Studio alone had entered the service (Sperling, 240). With so

many role models, America was encouraged to participate in the military

aspect of the war.

Hollywood

was an essential part in creating a positive war mentality where isolationist

fears once blocked America from helping Allied Europe. By the end of the

thirties, the American movie industry was the fourteenth largest business

in the country. Some members of this elite group were the stars of the

silver screen. With their talent and fame, they held a lot of influence

over the enamored public. Actors and actresses were the ones most responsible

for drumming up public acceptance of the war, since they were the most

visible members of the film community. The enthusiastic performers legitimized

the cause and defined the purpose of the war. They continued to boost home-front

morale and increase public support throughout the forties. At the beginning

of World War II, many citizens were reluctant to leave their safe and stable

lives to join the Armed Forces, but men were soon lined up to volunteer

their services to the government. Actors like James Stewart, Clark Gable,

and Ronald Reagan set a national example when they enlisted. Jimmy Stewart,

who had joined the Army Air Force Corps as a private, eventually advanced

to the position of lieutenant colonel. Later, after receiving the Air Medal

and the Distinguished Flying Cross award for his service in the United

States Air Force, Jimmy Stewart became a brigadier general in the Air Force

Reserve. Actor Audie L. Murphy also defended his country on the battlefields.

Murphy, who was a Staff Sergeant, became the most decorated soldier in

the history of World War II. For defeating an entire enemy infantry by

himself, Murphy was awarded with the Congressional Medal of Honor as well

as every other military honor available. In several cases, Hollywood stars

not only joined the army, but succeeded to the point of national recognition.

Their enlistments were not merely publicity stunts. According to Otto Friedrich,

the author of the book City of Nets, by October of 1942, more than

2,700 members of the Hollywood film industry had joined the Armed Forces

(Friedrich, 106) . At least one-fourth of the male employees at Warner

Brothers Studio alone had entered the service (Sperling, 240). With so

many role models, America was encouraged to participate in the military

aspect of the war.

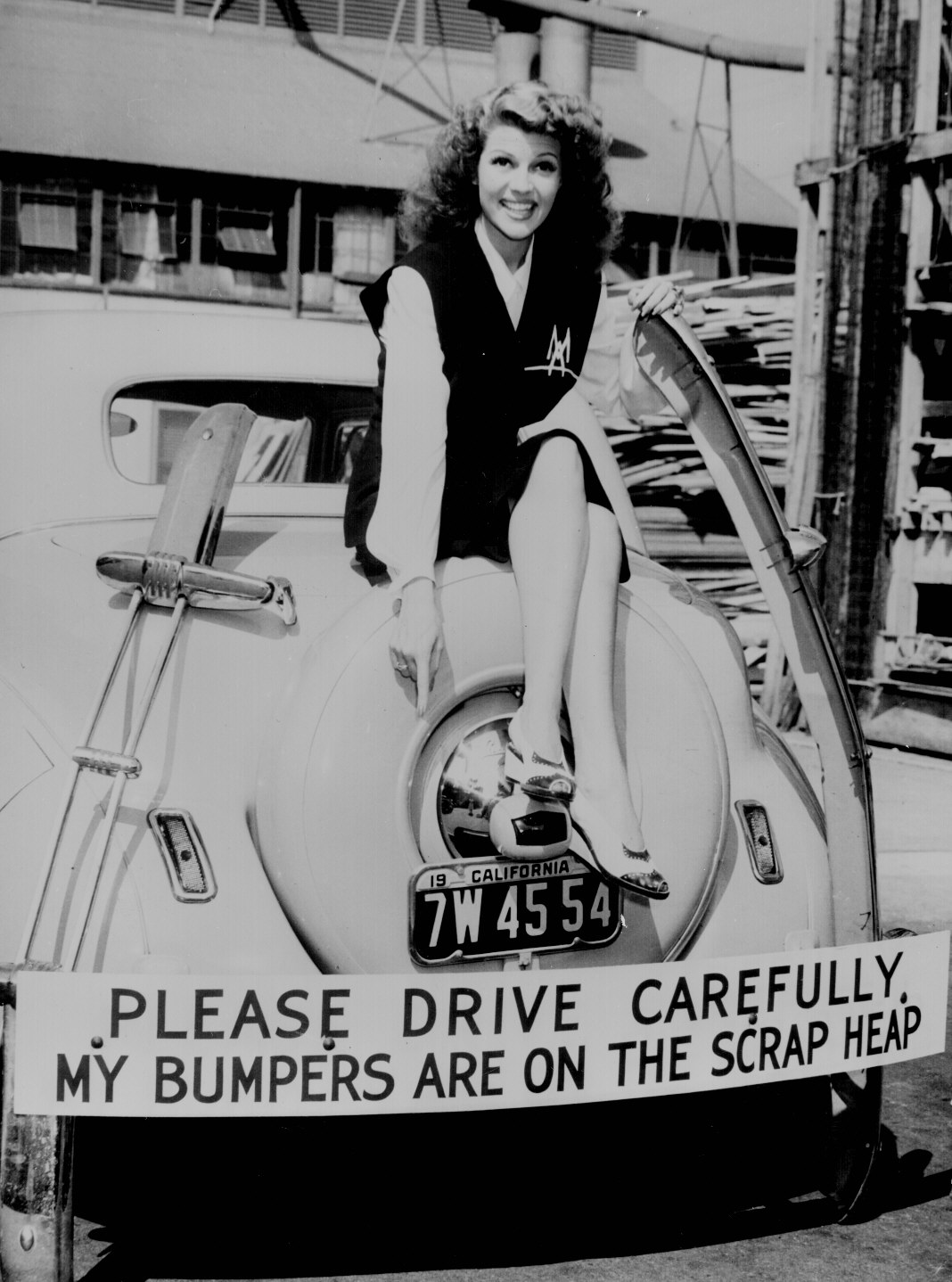

While soldiers were defending freedom against the enemy, citizens on the home front collected supplies to fuel the war machine. Not only the actors, but the movie theaters themselves played a significant role in home front war mobilization. Theaters served as collection grounds for materials like scrap metal, which the government tried to reuse during the war years. Actress Rita Hayworth was a famous icon of the scrap metal drive. She even donated the bumpers of her own car to the cause. Because many people visited the theaters, they were ideal locations to advertise the sale of war bonds. Some movie houses allowed customers to purchase war bonds on the spot. Theaters were also the place to make blood donations. Terrible violence on the European front had caused a serious shortage of blood among Allied soldiers. Famous stars often publicly donated blood to encourage the practice. Various theaters even accepted the blood donations as admission price to movies.

While the American public watched newsreels and war films looking for ways to participate, soldiers looked for ways to relax in a foreign land. Perhaps one of Hollywood’s most enjoyable roles was in its entertainment of the servicemen. In 1941, the United Services Organization (U.S.O.) was created. The organization was actually a conglomerate of six private groups that joined to provide activities for soldiers on-leave. Soon after the U.S.O.'s formation, hundreds of Hollywood entertainers volunteered to perform for the troops. Vaudeville shows and comical skits kept spirits positive and cheerful while troops were adjusting to life on the frontlines. Bob Hope and a cast of notable actors followed the GI troops and performed for them at various stations. The idea of military entertainment began when Hope and a number of other actors were still recording in Europe at the time war was declared. Leaving on the last boat for America, Hope watched as the battle anxiety of the passengers escalated to the point of sobbing. He consulted with the captain and suggested a performance for the weary travelers, and the idea of entertaining war troops was born. By the end of the war, over two thousand performers had entertained Allied soldiers overseas (Morella, 12).

Bob Hope expanded his war efforts to include an international U.S.O. tour, radio broadcasts from military bases, exhibition golf games, and the famous Hollywood Victory Caravan. Hope found several unusual ways to raise money for the war. He once volunteered to strip down to his shorts as an extra prize for the highest donator to the Red Cross Drive. During the summer months of 1942, Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, with the help of Samuel Goldwyn, performed shows and competed in war relief golf benefits.

Hope was also an active member of the Hollywood Victory Caravan, which was a group of twenty-one touring stars that performed a series of shows for the Army and Navy Relief Fund. The actors and actresses traveled the country by train, finally ending up in Washington D.C., where they presented a charity show for the Relief Fund. The Caravan was composed of such well-known entertainers as Desi Arnaz, Bing Crosby, Cary Grant, Claudette Colbert, Olivia de Havilland, and Groucho Marx. The stars staged a three-hour variety show of singing, dancing, and acting. After the Caravan put on the war relief shows, they would often perform a separate two-hour skit for the government issued troops. However, the actors didn’t seem to resent the exhausting routine as they continued to do it. Bob Hope admitted loving the performances but also conceded that the schedule was tough. Bob Hope and the Caravan completed a 65-show tour for the war troops. Afterwards, the Caravan began touring Alaskan bases. On the Alaskan tour, Bob Hope juggled numerous activities so that he could perform for the GI troops. Hope and the other performers went against all of the advisories saying that there simply was not enough time to complete an Alaskan series, and performed at many frigid military bases regardless. In addition, the group visited numerous hospitals to lift the spirits of the wounded. The Hollywood Victory Caravan also distributed films to army bases and military camps and had hopes of raising more than one billion dollars in war bonds. Hollywood supported the war cause by reshaping popular opinions of the conflict and trying to keep a positive outlook.

Like many

other programs, The Hollywood Canteen mixed fame with the public in hopes

of enhancing Allied confidences. The Hollywood Canteen, which was a popular

military nightclub, strengthened the soldiers by allowing them to relax

and regroup before leaving for the front-line. Because many soldiers passed

through Hollywood before being transported to the Pacific, Tinsel-town

natives, specifically John Garfield, conceived the idea for the Hollywood

Canteen. Formed in October of 1942, the Hollywood Canteen was a place that

offered servicemen the opportunity to mix and mingle with the hotshot stars

of Hollywood. Actress Bette Davis, with the help of Jules Stein, persuaded

Warner Brothers to produce a film by the same name to endorse the club.

In addition to producing the movie, WB Studios donated some of the proceeds

to help finance the operation of the Canteen. Bette Davis was also the

president of the Canteen, which raised money by charging admissions and

receiving donations from its customers. Some two million servicemen frequented

the club during the war. The Canteen had a staff of 50,000, many of which

were popular Hollywood entertainers (Morella, 12). Members of the staff

worked on a volunteer basis and received no pay for their services. The

actresses who worked at the Canteen danced with the soldiers, signed autographs,

prepared the food, and even washed dishes. Actress Hedy Lamarr once said,

‘ “…I couldn’t cook. I was a mess in the kitchen. I would wash dishes gladly

(Friedrich, 108).”’ The Canteen and its famous volunteers recognized and

commended the efforts of the servicemen. The soldiers were sacrificing

much to participate in the war and Hollywood was eager to support their

efforts and cater to their needs, just has Hollywood was also ready to

assist the government.

Like many

other programs, The Hollywood Canteen mixed fame with the public in hopes

of enhancing Allied confidences. The Hollywood Canteen, which was a popular

military nightclub, strengthened the soldiers by allowing them to relax

and regroup before leaving for the front-line. Because many soldiers passed

through Hollywood before being transported to the Pacific, Tinsel-town

natives, specifically John Garfield, conceived the idea for the Hollywood

Canteen. Formed in October of 1942, the Hollywood Canteen was a place that

offered servicemen the opportunity to mix and mingle with the hotshot stars

of Hollywood. Actress Bette Davis, with the help of Jules Stein, persuaded

Warner Brothers to produce a film by the same name to endorse the club.

In addition to producing the movie, WB Studios donated some of the proceeds

to help finance the operation of the Canteen. Bette Davis was also the

president of the Canteen, which raised money by charging admissions and

receiving donations from its customers. Some two million servicemen frequented

the club during the war. The Canteen had a staff of 50,000, many of which

were popular Hollywood entertainers (Morella, 12). Members of the staff

worked on a volunteer basis and received no pay for their services. The

actresses who worked at the Canteen danced with the soldiers, signed autographs,

prepared the food, and even washed dishes. Actress Hedy Lamarr once said,

‘ “…I couldn’t cook. I was a mess in the kitchen. I would wash dishes gladly

(Friedrich, 108).”’ The Canteen and its famous volunteers recognized and

commended the efforts of the servicemen. The soldiers were sacrificing

much to participate in the war and Hollywood was eager to support their

efforts and cater to their needs, just has Hollywood was also ready to

assist the government.

The United States government depended on the financial assistance that Hollywood provided. Jack Warner, and owner of Warner Brothers Studios, encouraged his employees to make donations to the Red Cross Drive. WB Studios also made pay-cuts to compensate for their contributions. Warner’s voice could often be heard telling his workers to ‘tighten their belts.’

Government bonds were also issued to private citizens in hopes of raising financial aid for wartime supplies. Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, selected Howard Dietz, the MGM publicity director, to endorse the sale of the war bonds. Dietz then selected Clark Gable, the president of the Hollywood Victory Committee, to organize the bond sales. Gable chose gorgeous pin-up girls like Hedy Lamarr and Lana Turner to promote the bond sales. The ladies often raised bond money by kissing men, but for a price. A kiss from Lana Turner would set a man back $50,000 dollars in war bonds. In one single day, Lamarr once generated more than $17 million dollars in war bond sales. The glamorous Dorothy Lamour sold a total of $350 million dollars in nearly four days (Friedrich, 106).

Some performers felt the need to individually donate money to war related foundations. Actress Joan Crawford gave the Red Cross charity her salary from one of her movies; it totaled $112, 000. Cary Grant made a contribution of $100,000 to a combination of both British and American foundations. By 1945, Hollywood’s financial contributions to the war included $1 million dollars to the United Services Organization, more than $1 million dollars to the war bond drive, and more than $2 million dollars for the Army and Navy Relief Fund (Morella, 14).

Not only did Hollywood help the war, but the war also helped Hollywood. During this time, a number of propaganda films and documentaries were produced by government decree. Films and newsreels were a few of the most popular media venues in a pre-television saturated society. As early as December of 1938, the War Production Code Administration sent an internal memo to Hollywood asking, ‘ “ Are we ready to depart from the pleasant and profitable course of entertainment to engage in propaganda (Koppes, 17)?” ’ But the question was almost unnecessary because the members of Hollywood embraced the war and supported it in every possible way. ‘ “A number of Hollywood people, like James Stewart and Tyrone Power, had served with great distinction in active combat. Others, like directors Wyler, Huston, Ford, and Capra, did their soldiering as filmmakers, often close to or in the midst of dangerous fighting (Custen, 261).”’ The production of war movies was necessary in order to recognize the soldiers’ efforts, to increase general support for the war, and to keep the public informed. Even before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hollywood began creating films, which depicted characters joining the service or working to support the war cause. James Stewart and Clark Gable starred in Winning Your Wings and Wings Up, respectively. After the release of these movies, thousands of men entered the Air Force, following the examples of Stewart and Gable. Jack Warner produced Winning Your Wings, which was an Army Air Corps training film. Of the 100,000 men that this movie helped recruit, Jimmy Stewart was one. When she narrated a film called Women in Defense, Katharine Hepburn did her part by encouraging women to work in war factories or enter the Armed Forces. Tinseltown bigwigs like Irving Berlin and Frank Capra produced a string of films that were based on the war. Berlin’s creation, This is the Army, was a military comedy that offset Capra’s somber Why We Fight series. Frank Capra, who was a colonel in the United States Army, produced the series of seven films to convince people to abandon their former isolationist beliefs. Many of these movies were used in newsreel production and shown prior to the featured presentation in the theaters. The films were informative and also immensely entertaining and appealing to society. As author Judith Crist said, “…the films…prepared Americans, at least psychologically, for the struggle (Morella, 15).” Portions of the profits from these films were donated to help finance the war.

Hollywood was also responsible for filming countless training movies for the Army and the war-production industry. The instructional pictures shortened previous training times and allowed workers and soldiers to begin their duties sooner. Movies aided in familiarizing soldiers with foreign terrain, identifying aircrafts, simulating aerial combat. Even Walt Disney turned out training films, documentaries, and animated cartoons that assisted the war effort. The animated Donald Duck boosted home-front morale and encouraged people to get involved, while Bugs Bunny sang “Any Bonds Today?” Disney’s The New Spirit persuaded citizens to pay their income taxes, while Get in the Scrap promoted the act of scrap metal collecting to conserve resources. Under the direction of the Bureau of Motion Pictures, Hollywood even tried to appeal to the younger generation to help with the war effort. Children were depicted in films collecting scrap metal, growing Victory gardens, and saving loose change for future war bond purchases.

Darryl Zanuck, of Twentieth Century Fox, produced many propaganda films, among which were To the Shores of Tripoli, Secret Agent of Japan, and A Yank in the RAF. Because of Zanuck’s tremendous contributions, he was named an honorary colonel in January of 1942. Darryl Zanuck traveled to North Africa, Alaska, and England to supervise the training film and documentary production. ‘ “ The films showed citizens making little sacrifices without complaint – buying bonds, donating blood, volunteering for the Red Cross, putting up with rationing (Koppes, 143).”’

Another big production company, Warner Brothers Studios, participated in the propaganda business as well. ‘” In the hands of motion picture makers lies a gigantic obligation… We must have the courage and the wisdom to make pictures that are forthright, revealing and entertaining, pertinent to the hour and the unpredictable future,”’ commented producer Jack Warner (Sperling, 245). His brother Harry Warner took on a similar ambitious attitude when confronted with the war issue. ‘ “Our company is about to start the largest program that has ever been undertaken to be made by any company in the industry. We have agreed to make from four to five hundred reels of training pictures in the coming year. We are also going to make Irving Berlin’s This is the Army… I don’t want to make a single dollar of profit out of these pictures (Sperling, 240).”’ Warner Brothers Studios were charged with producing This is the Army, an Irving Berlin screenplay. In addition to refusing profits from the films, Warner Brothers Studios donated seven million dollars to the Army Emergency Relief Fund (Sperling, 251). Warner Brothers Studios was also the studio that filmed the movie, The Hollywood Canteen, to benefit the actual establishment. After the movie’s release, Harry Warner gave the Canteen forty percent of the film’s profit to help rehabilitate wounded servicemen. Between the years of 1942 and 1944, Hollywood produced nearly 375 propaganda films for the government (Morella, 57).

The World War II era Hollywood was a significant force in unifying Americans across the continent. While the war was raging throughout the rest of the world, the Hollywood community successfully managed to keep calm and persuade the American public to do the same. Assistance came from all areas of Hollywood, as directors, actors, and workers joined together with the general public to strive for the common goal of victory. Starting even before the United States entered the war, Hollywood boosted American confidence and supplied the government with money and support. The film community and the United States government combined federal power and business enterprise to fight the enemies, with successful results. World War II inspired Hollywood to produce some of its most memorable works, while Hollywood gave moral and financial support to the cause. Bob Hope said it best of all, as he performed for thousands of troops…. “Thanks for the memories (Hope, 384)!”

Custen, George F. Twentieth Century’s Fox. New York: Basic

Books, 1997. pgs 257-308.

Doherty, Thomas. Projections of War. New York: Columbia

University Press, 1993.

Faith, William Robert. Bob Hope: A Life in Comedy. New

York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1982.

Friedrich, Otto. City of Nets. New York: Harper and Row

Publishers, 1986.

Hope, Bob. The Last Christmas Show. New York: Doubleday

& Co., 1974.

Koppes, Clayton and Gregory Black. Hollywood Goes to War.

New York: The Free Press, 1987.

Morella, Joe and Edward Z. Epstein and John Griggs. The Films

of World War II. New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1980.

Sperling, Cass Warner and Cork Millner. Hollywood Be Thy Name.

California: Prima Publishing, 1994.

http://www.gliah.uh.edu/modules/ww2/index.cfm

This site gives a general overview of world war two, but also has information

concerning Hollywood’s involvement in the war. It briefly discusses the

atmosphere of wartime Hollywood, films made during that era and Hollywood’s

reaction to the war.

http://www.militarymuseum.org/1stmpu.html

The site explores the military aspect of Hollywood’s involvement. It

gives some in-depth facts about specific actors.

http://library.thinkquest.org/21065/hist.htm

This is a site that gives a general historical overview of Hollywood

from 1895-1960.

http://www.cmohs.org/recipients/audie_murphy_citation.htm

This site explains the duties for which Audie Murphy won the Congressional

Medal of Honor.

http://www.medalofhonor.com/MedalOfHOnorAudieLMurphy.htm

This site chronicles the major events of the life of Audie L. Murphy:

film star and military hero.

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/bobhope/

This link gives information about actor Bob Hope and his involvement

with World War II.

Site Created by:

Angel Annacchino