|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

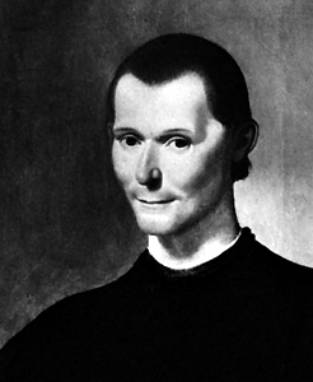

Machiavelli was a great political philosopher who

lived in Italy during the height of the Renaissance. He lived his life

searching for the real answers behind politics in the hopes that one-day

Italy might be united to achieve its former glory as a world power. Today,

Machiavelli is widely known for the controversial political views found

in his masterpiece, The Prince.

After the Black Death swept across Europe during the fourteenth

century, the general attitudes of the people began to change. The Catholic

Church had been powerless to stop the onslaught and chaos brought by the

plague. This caused people to seek answers elsewhere, beyond the dogma

of the church. Scholars looked towards the ancients of Greece and Rome

as models for their inquiries into the human world. Individualism, secularism,

and humanism replaced grace and divinity. By the time Machiavelli was born

in Florence in 1469, Italy was experiencing a Renaissance, a rebirth of

classical literature and ways of thinking.

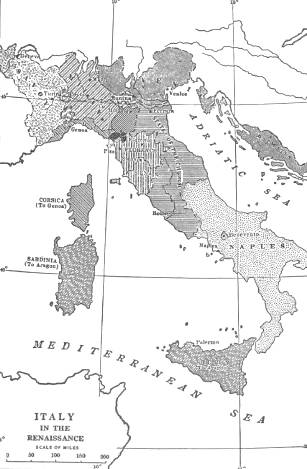

The Italy of Machiavelliís time was in a state of

political confusion. Foreign armies clashed on Italian battlefields in

hopes of conquest. Powerful Italian families battled for control of the

countryside. City-states and territories dotted the Italian landscape.

Alliances were forged and broken. The papacy was becoming increasingly

corrupted, and foreign mercenaries were being hired to fight for the Italian

cause. Italy lacked the general political stability and unity that scholars

were finding had existed before the Catholic Church during the time of

the Romans.

Machiavelli

officially began his political career in 1498, at the age of twenty-nine.

That year, Machiavelli was given the position of Chancellor and Secretary

of the Ten of Liberty and Peace in the Republic of Florence. Machiavelliís

job in the Florentine Republic allowed him to travel abroad on diplomatic

missions and see how other successful governments functioned. He met with

many famous leaders such as Luis XII of France, Cesare Borgia (son of Pope

Alexander VI), Pope Julius II, and Emperor Maximilian I of the Holy Roman

Empire. His travels made him realize that both political power and stability

were possible if the right formulas were followed.

In 1512, the

Medici family took over Florence and the republic was dissolved. Machiavelli

was removed from office and, after he was suspected in an anti-Medici plot,

he was imprisoned and tortured. Machiavelli was released from prison in

1513 and decided to retire to his countryside home of San Casciano. It

was there that Machiavelli composed his most famous works, The Prince

(1513), and The Discourses (1513-19). In the lush countryside of

San Casciano, Machiavelli also wrote the, Art of War (1521), and

the History of Florence (1525).

When the Medici

presence in Florence was overthrown, Machiavelli hoped to regain his position

in the republic. He returned from his exile to Florence in 1527. Machiavelli,

however, was not that popular in Florence. Some people suspected him of

being pro-Medici; others feared him because of his deep political insights.

At 58 years old, Machiavelliís health was beginning to deteriorate. He

grew sick and died in 1527, never fully achieving the political power he

desired.

Machiavelliís

works, however, leave him a legacy far greater than any political title

could have given him. His views on politics set him apart from any other

political philosopher before him. Following true Renaissance style, Machiavelli

looked to the past to supply answers for the present and future. Machiavelli

engrossed himself in classical literature and in the study of ancient leaders.

He compared ancient leaders and ancient situations to the leaders and the

events of his own time. Machiavelli wanted to know the method to achieve

political success, and how this method could be used to unite Italy.

Machiavelli

believed in a cyclical view of history, that situations in the present

are mimetic of past situations. With this in mind, all the answers to current

problems could be found in the past. By exposing the mimetic aspects of

history, Machiavelli was able to find historyís didactic nature. History

was instructional, one could learn from the past to obtain the answers

he was looking for.

Machiavelli

also probed deep into the conflict between politics and ethics. Politics,

matters of state, were always of the utmost importance. To Machiavelli,

the state was the primary good. The state provided security and freedom

for its citizens; therefore everything must be done in order to maintain

it. This belief placed political leaders above ethical standards. In the

words of Machiavelli, ďthe ends justify the means.Ē Leaders must do everything

they can to support the state, even if their actions at times seem unethical.

By placing

the state as the primary good, Machiavelli was able to examine corruption.

Corruption of the state occurred when a leader placed some secondary good

(material wealth/status) above the primary good (the state). So long as

the state remains the primary good, the government will be powerful and

the people will be secure.

Machiavelli,

like the ancient Romans, recognized that republican forms of government

could be too slow to act during times of necessity. For this reason, Machiavelli

saw no fault in the temporary leadership of a prince or a dictator during

times of crisis. As long as the state always remains the primary good,

the government will be just. Also, a dictator or prince must never have

the power to change the traditional laws governing the leadership of the

state. In such a case, individuals can place their own ambitions (secondary

good) above the state (primary good) and corruption develops. Machiavelli

favored republics like his own Venice, but recognized that under certain

conditions or times of crisis, rule must be passed to one individual for

drastic action. The ability of an absolute ruler to obtain fast action

led to Machiavelliís quest for a great Prince. A great Prince, he believed,

could act fast to rid Italy of its foreign occupation and unite the Italian

people. Once the Prince had restored and reunited Italy, steps could be

taken to redevelop the republic and Italy would be great again. Machiavelli

also believed that a strong state must have a strong military. A strong

military, made up of citizen soldiers, works to continuously enforce the

powers of the state, and thus upholds the primary good. Citizens should

be freed from their obligations to the church because the church suppressed

arête

(valor, courage, and the honor of a warrior) and preached humility and

meekness. In this light, Machiavelli believed in strong secularism. According

to Machiavelli, citizens should place nothing (not even God) above the

state. The state and the state alone existed to provide citizens with security.

Machiavelliís works have given birth to a new political era. Many of

the ideas and methods developed by Machiavelli and other Renaissance philosophers

are still in practice today. Machiavelliís call for secularism is still

reflected in modern governments through separation of church and state.

His approach towards treating the problems of mankind as a science is still

mirrored by todayís social scientists. The method of solving current problems

by comparing them to past situations is still used by contemporary historians,

politicians, and economists. Ideas and methods first developed by Machiavelli

have stood the test of time to prove that Machiavelli was truly a great

philosopher.

Bondanella, Peter and Mark Musa. The Portable Machiavelli.

New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1979.

Butterfield, H. The Statecraft of Machiavelli.

London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd., 1979.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. The Art of War.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. The Discourses.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. The History of Florence.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. The Prince.

Sullivan, Vickie B. Machiavelliís Three Romes.

DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1996.

http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~pgrose/mach/

-Huge list of Machiavelli links. On

his travels, and in his quest into ancient literature,

On

his travels, and in his quest into ancient literature,

Barricelli, Jean-Pierre. Machiavelliís The Prince: Text and Commentary.

Woodbury: Baronís Educational Series, 1975.

http://www.ctbw.com/lubman.htm

-Nice summary of Machiavelliís life with a black and white picture of Machiavelli.

http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/m/machiave.htm

-Short article about Machiavelli with an analysis of key points in The

Prince.

http://radicalacademy.com/philmachiavelli.htm#Machiavelli

-Analysis of Machiavelliís life and political beliefs.

http://www2.lucidcafe.com/lucidcafe/library/96may/machiavelli.html

-Brief article on Machiavelli with links to other related philosophers.

Site created by: Al Sabin