|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

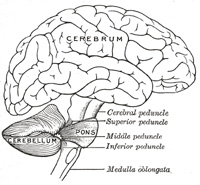

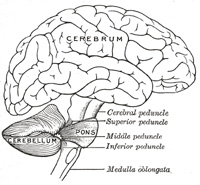

Mental illness has been around since the

dawn of civilization. Scholars as early as Hippocrates, an ancient

Greek physician, studied it. He is thought to be the first person

to declare that mental illness had a scientific explanation, and that it

had nothing to do with Gods or spirits. He concluded that instead,

it was the brain that must be the “source of our pleasures, joys, laughter,

and jests as well as our sorrows, pains, griefs, and tears.” (Wade, 13)

No historical period, however, has shown more interest in the topic than

our own. The growth in interest and progress made since the late

1800’s has been drastic. In less than 150 years, western society

has gone from throwing its mentally ill into jails to the use of medicines

and therapy. Once a taboo topic to be silenced, mental illness has

become the subject of open and frequent discussion and study. The

late nineteenth century marked the emergence of “psychology”: the

study of human behavior and mental processes and the conditions that influence

it. The scientific study of these topics permanently changed the

face of western society.

Before the “science” of psychology was developed, conditions for the mentally ill were extremely deplorable. Most people with mental illnesses were seen as either failures or victims of some mysterious force. Many felt that the mentally ill brought it upon themselves, through moral or religious transgressions. They felt that gods or other spirits were punishing these “criminals” with illness. Others were thought to be under the spell of evil spirits, the devil, or the victims of witchcraft. One common explanation held that the mentally ill were under the influence of the moon. The Latin word for moon is “luna,” which led to the term “lunacy.” No matter the reason, early western civilizations certainly did not see mental illness as the result of biology or upbringing, as most psychologists do today. The implications in these theories for treatment were at best unproductive, and at worst was shameful and inhumane. The mentally ill were seen as incurable, subhuman creatures, and were treated likewise. The most common “treatment” in the eighteenth century was to simply throw the patient into a jail with criminals. When they became restless, they were fitted with straightjackets or ankle and leg restraints. (Porter, 98) Other torturous devices were used in the name of “convincing” the ill, who were thought to be choosing to act the way they did. Corrections officers often felt that the ill simply had to be coerced into acting like a normal person. This type of treatment had disastrous effects on the patient, usually driving them farther into psychoses than they already were. (Porter, 103) Restraining devices like the “protection bed” and the “tranquilizer chair” were frequently used. The protection bed consisted of a large, coffin-sized box with screens on the top and sides. It was scarcely larger than a human body, and while confined the patient was not fed, talked to, or allowed to excrete wastes. The tranquilizer chair had leather straps used to tie down the patient’s arms and legs, a small box to put over his or her head, resembling a modern day electric chair. (Porter, 109) Both devices cut off the patient’s sensory abilities, which recent research has shown to cause delusions. (Pert, 234-5) Patients were left in these devices for long periods of time and only let out when they “decided” to get rid of their illness.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the fashionable way to deal with the mentally ill was changing. Instead of punishing them, many sought to try and “cure” the ill, though conditions were not necessarily better. Curious physicians tried to study their patients in an effort to better understand mental illness. These experiments were often cruel and devistating to the patient. In order to learn how to calm the patients during bouts of hysteria, physicians sometimes issued the patient tranquilizing chemicals. They were often administered in doses that could put a person into a coma or permanently incapacitate them so that they were worse off than before the treatment. Other patients were purposely given diseases or fever in order to “shock” them out of their illness. (Porter, 167) By injecting the patient with malaria, doctors found that the progression of paresis could be halted. The patient was then given quinine to combat the malaria. This treatment, cruel as it was, offered one of the first hopes that biology could help persons with severe mental illness. All of these methods were, however, more in the interest of ridding society of the mentally ill, and not necessarily on healing the sick individual. The second half of the nineteenth century, on the other hand, would bring revolutionary changes in the perception of the mentally ill.

Enlightenment.

Enlightenment thinkers held that there was a scientific explination to

all aspects of life, including politics, economics, and social development.

Early psychologists simply applied this principle to the human psyche.

Wundt had many students, and often held workshops and classes in his laboratory.

Him and his followers concentrated mainly on sensation and perception,

reaction times, imagery, and attention. (Wade, 17) This is a very

narrow range of topics compared to the scope covered by today’s psychologists.

He is famous for the “trained introspection” method, in which subjects

were trained to carefully observe, analyze and describe their own sensations

and emotions. These observers had to make over 10,000 “practice observations”

before they were allowed to participate in an actualy study, and could

take up to 30 minutes to describe an experience that lasted only a few

seconds. Subjects, for example, could be flashed a picture of an

apple for a second or two. They would then be asked to describe the

variety of mental processes they went through upon that observation.

Wundt’s hope was to boil down the human experience of perception to its

bare bones, and to therefore decipher part of the mystery surrounding human

thought. (Reiber, 78) As Wundt and his colleagues started to uncover

the secrets behind human thought, the people of his time began to look

at the brain and its functions in a much more serious light. It was

suddenly very plausible to think that mental illness could in fact be caused

by something in a person’s brain that was outside of his or her own control.

Enlightenment.

Enlightenment thinkers held that there was a scientific explination to

all aspects of life, including politics, economics, and social development.

Early psychologists simply applied this principle to the human psyche.

Wundt had many students, and often held workshops and classes in his laboratory.

Him and his followers concentrated mainly on sensation and perception,

reaction times, imagery, and attention. (Wade, 17) This is a very

narrow range of topics compared to the scope covered by today’s psychologists.

He is famous for the “trained introspection” method, in which subjects

were trained to carefully observe, analyze and describe their own sensations

and emotions. These observers had to make over 10,000 “practice observations”

before they were allowed to participate in an actualy study, and could

take up to 30 minutes to describe an experience that lasted only a few

seconds. Subjects, for example, could be flashed a picture of an

apple for a second or two. They would then be asked to describe the

variety of mental processes they went through upon that observation.

Wundt’s hope was to boil down the human experience of perception to its

bare bones, and to therefore decipher part of the mystery surrounding human

thought. (Reiber, 78) As Wundt and his colleagues started to uncover

the secrets behind human thought, the people of his time began to look

at the brain and its functions in a much more serious light. It was

suddenly very plausible to think that mental illness could in fact be caused

by something in a person’s brain that was outside of his or her own control.

One of Wundt’s students, E.B. Titchener, brought Wundt’s methods to the United States. He called the methods “structuralism” because Wundt’s goal was to break perception down to its bare “structure.” (Morris, 16) This method, however, soon came to its demise. It did not prove to have much practical signifigance. As put by Wolfgang Kohler, a student of Titchener’s, “What had disturbed us was…the implication that human life, apparently so colorful and so intensely dynamic, is actually a frightful bore.” (Rieber, 242) Once the elements of perception were broken into their separate blocks, then what? It did not answer the pressing questions of how and why the psyche acted as it did, it only attempted to explain what it did. The structuralists’ methods were also unreliable, since different individuals all had different perceptions of the same experiences. (Wade, 17) It was hard for the structuralists to come up with any sort of reliable findings since sensory perceptions are strictly subjective. In spite of its imperfections, however, structuralism introduced the West to the science of psychology that would become such prevelent part of its society.

William James, an American psychologists, reformed the structuralist views and atempted to discover the “how and why” aspects of human behavior. James was inspired by the ideas of the British naturalist Charles Darwin. Darwin, also a child of the Enlightenment, thought that biologists should not only describe an organism, but should question why it had those certain attributes. What, Darwin ventured to ask, was the evolutionary benefit of a certain trait? James also looked for the underlying cause of certain traits – namely, of human behaviors and mental processes. (Wade, 18) James’ psychology was labelled “functionalism,” and it too was destined to be short lived. James’ ideas, though ambitious, lacked the precise scientific theory that people of the time demanded. Its emphasis on the causes of behavior, however, would set the course of psychological science for the rest of its development.

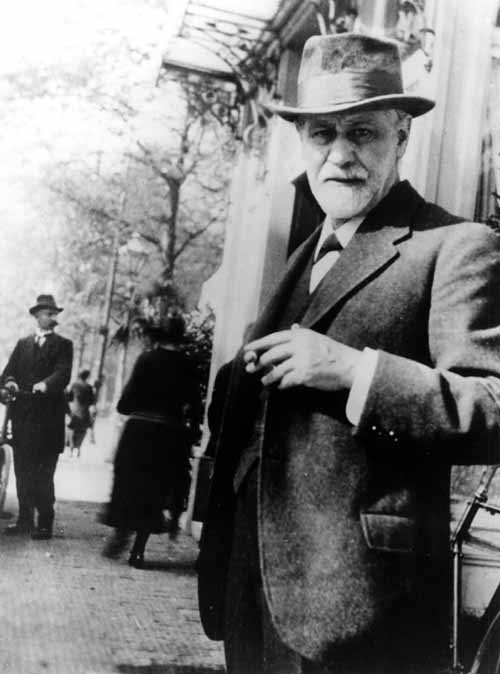

The psychological theory that Freud developed is called the “psychodynamic” theory. It focuses on internal wishes, impulses, and desires, and the subjective aspect of a person and his or her personality. Freud placed a strong emphasis on the past, and felt that one’s personality was formed by the age of eight. (Wade, 24) Events that occurred in this period, then, would shape a person for the rest of his or her life. Freud used several methods to learn subjectively about his patients’ personalities. He called dreams the “royal road to the unconscious,” and analyzed the content of his patient’s dreams. He looked at dreams mainly in terms of repressed anxieties. He also had his patients make free associations. In this method, the patient is made to feel very comfortable and relaxed, and then told to say the first word that comes to their mind when his psychologist presents a word or picture. Freud also noted a patient’s parapaxes, or “slips of the tongue:” he felt that the things we do or say without really thinking about them were deeply revealing. (Hall, 17) Freud analyzed (hence, the term “psychoanalysis”) what his patients said or did in these situations, and from that, came up with what he felt to be the patient’s central problem. Freud often felt that the problem was due to repressed feelings from a traumatic childhood event. A famous saying about Freudian psychology is: “you are what you were,” which is to say that who you are today is stems strictly from events in your childhood and their effect on you. (Wade, 23) The psychodynamic theory, then, is often accused of undermining the biological and chemical aspects behind a person’s behavior. Even today, one can see the effects of Freud’s ideas on mainstream culture. If one walks into any bookstore, there will most likely be a book on analyzing dreams. Freud was the first psychologist to use “couch therapy:” the method where the patient, laying down on couch, rambles on about his problems without much intervention from the psychologist, who simply takes notes on what the patient says so that he or she can analyze them later. This is the image presented in most pop-culture representations of a psychologist.

Freud held that there were three aspects in personality: the “id,” the “ego,” and the “superego.” The id was the instinctual part of personality. Its only goal is primitive, immediate pleasure, and it avoids anything negative. It is selfish and irrational, and focused primarily on physical desires like food and sex. The ego gets is energy from the id, though it is more rational and responsible. It uses reason and makes objective decisions. The ego, according to Freud, is the most conscious part of the personality. It holds the “manager” position and is always in control – it takes care of the person and makes sure the id gets what it wants. The superego contains a person’s set of moral principles. It represents the social reality and is conscious that some things are “wrong,” even when the ego might feel that they are good. (Wade, 24) In the cartoonish image of an angel and devil sitting on a person’s opposite shoulders, the id would be the devil and the superego, the angel. The ego would be the head between them. This concept is one of the most striking examples of Freud’s highly conceptual ideas. None of his theories were founded on scientific research, and he held next to no discussion about the brain. They were strictly speculative. Once he began practicing his methods on patients, scientific research on their results did occur, but the theories themselves were wholly Freud’s brainchildren.

After World War I, many soldiers returned with “shell shock,” or what is now called “post-traumatic stress disorder.” This made mental illness a much more visible part of society, and people were looking for explanations and cures. This is the breeding ground in which Freud’s ideas grew. Freud had a particularly traumatic childhood, and he was addicted to cocaine, but these biases were largely ignored. (Hall, 16) Freudian theory presented a clear, though very reductionist solution to a growing problem, and this is what people needed. Freud highlighted the immense complexity of the human psyche, and opened the door that Wundt created to inconceivable widths. Psychology was now a household term, and a fashionable thing to practice. Many modernist artists, writers, and scholars saw their “shrink” on a regular basis and discussed it openly. People began to see psychologists for “maintenance” reasons even if they weren’t ill. Friends tried to analyze their friends’ problems, writers analyzed society’s problems, and artists analyzed their own problems. Freud’s psychoanalysis had become an unstoppable aspect of western society. What started out as a solution to a problem became a whole new way for the West to see the world. All good things must, however, come to an end, and Freud’s psychodynamics eventually became less popular with the development of new theories.

Freud's analysis helped to foster an environment of intense observation. All subsequent theories and schools of psychologists followed this method: making careful observations and then analyzing the data. Later research developed new ways of reading people's sensory responses, led to a greater understanding of the nervous system and the endocrine system, and continued to discover new pharmacuticals. Though the methods and eqipment have become more advanced, and the focuses have changed with the times, psychology has continued to develop in the manner it's forefathers presecribed: careful scientific observation and analysis, and open discussion.

The growth of psychology in popular culture led to many important changes in the perception of mental illness. It was no longer seen as an incurable disease to be punished and hidden. People began to understand that certain behaviors were due to disease or personal trauma, and that punishing a patient would not cure them. Western society became extremely interested in brain and it’s workings. Up until the twentieth century, the brain remained a mysterious organ that was often speculated on, but seldomly researched. Interest in Freudian psychodynamics spurred more research, more sponsorship, and more education. Today, seeing a psychologist to help deal with problems like depression is highly suggested among health professionals and is quite common. The mentally ill are treated with much more compassion than they were 100 years ago, and this compassion will only grow with research. Everyday scientists are learning more about how human mental processes work and why people behave the way they do. As perceptions change, so do treatments. Most mildly ill patients are referred to a counseling psychologist. A counseling psychologist often simply gives the patient someone to talk about his or her problems with and offers suggestions. More severe cases are handled by a psychiatrist, who holds a PhD and can prescribe medications to help curb a patient’s symptoms. (Morris, 11) The journey to complete understanding, however, is still far from over. There are many aspects of human psychological function that remain unknown. Also, care for the mentally ill is far from perfect. The vast majority of the West’s mentally ill can be found on the streets, because they cannot afford the help they need, or do not know that they are mentally ill in the first place. (Morris, 126) The emergence of a “psychological science” has, however, at least made these issues prevalent. It has made enormous progress for such a young study, and only time will tell what changes will come with future research.

1) Rieber, Robert W. Wilhelm Wundt in History: The Making of

a Scientific Psychology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001.

2) Hall, Calvin, S. Primer of Freudian Psychology.

New American Library, 1997

3) Freud, Sigmund and Brill, A.A. Basic Writings of

Sigmund Freud. Modern Library, 1995

4) Morris, Charles G. and Maisto, Albert A. Psychology:

An Introduction. Prentice Hall, 1999

5) Wade, Carole and Tarvis, Carol. Psychology.

Prentice Hall, 2000

6) Porter, Ray. Madness: A Brief History. Oxford

University Press, 2002

7) Palmer, Ann. "20th Century History of the Treatment of Mental Illness"

April 2002. <http://intotem.buffnet.net/mhw/29ap.html>

http://bipolar.about.com/library/weekly/aa010101a.htm - An article titled "Reflections on the Millenia: Mental Illness in the Past and Future." One person's thoughts on the current state of mentall illness

http://www.epub.org.br/cm/n04/historia/shock_i.htm - The History of Shock Therapies in Psychiatry

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dh35lo.html - Moniz develops the lobotomy for mental illness in 1935

http://www.missioncreep.com/mw/estate.html - "Black hoods and iron gags;" an article on the experiments performed at Eastern State Penitentiary

http://www.cnn.com/HEALTH/9510/mental_history - Article titled "From shackles to Compassion," about an early practitioner of humane treatment

Site Created by: Ashley E. Tremain