After its

start in China, go spread throughout East Asia, ending up as major parts

of the cultures of Japan and Korea as well as China. The growth of

the game took different roads in each country, with rules and its place

in culture changing over time.

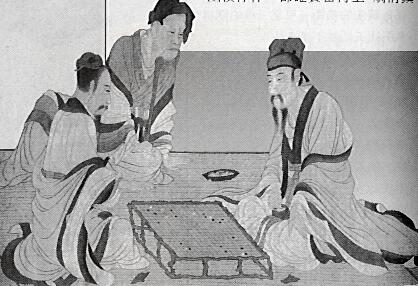

China

is the obvious place to start, as the game first developed here and has

had the longest time to be a part of the culture. Some of the earlier

definite references to Go can be seen in the works of Confucius. He makes

mention of it in an unflattering manner, causing future generations to

at times regard Go as un-Confucian. Later it begins being known as

a game of skill and those who are good at it tend to be known as wise men. China

is the obvious place to start, as the game first developed here and has

had the longest time to be a part of the culture. Some of the earlier

definite references to Go can be seen in the works of Confucius. He makes

mention of it in an unflattering manner, causing future generations to

at times regard Go as un-Confucian. Later it begins being known as

a game of skill and those who are good at it tend to be known as wise men.

At this period

in time it appears that the game was played on 17x17 boards rather then

the 19x19 boards used today. It is unclear when and why the change

occurred, but there is evidence that they were both in use for some time

together before 19x19 boards became the general type used. For example

in Tibetan Go a 17x17 board is still used today, making it seem obvious

the switch to 19x19 boards was not universal.

Another difference

that existed in early Chinese Go was the concept of placement. In

placement, four stones are placed on the board before play, black stones

diagonal corner star points and white stones on the other diagonal corner

star points. This would end up limiting Chinese Go players as other

countries had gotten rid of that rule and allowed for more inventive openings

that led to all sorts of new strategies. By the time placement was

gotten rid of in China, they lagged far behind other countries. Eventually

the “Chinese” opening was developed as it was one the other countries had

not seen before and could help keep Chinese players on even ground to continue

the game.

In China today

there are many top world players living there or that have come from there.

The top women's player in the world, Rui Naiwei, is from China and was

the first woman ever to win a major open title. Other pro players from

China consistently play well against international competition, not quite

as well overall as the Korean players, but better overall then Japanese

players.

The next country

to look at is Korea. As in other countries, the game began as something

for the aristocracy. It was seen as a romantic pursuit for the scholarly

and wise.

In 1592 after

the Japanese invaded Korea, Go began to be popular among the middle class

as still one of the important arts all wise and scholarly people were good

at. It was played by many a commanding officer Korea during the conflict

with Japan. This style of Go was still the old style brought from

China many hundreds of years before but a new style was developed, Sun

Jang Baduk. In this style 16 stones are first placed on the board

and then with the first move by black is placed on tengen, the center star

point. This style forced fighting in the early game and made many

Korean plays very adept at dealing with any situation that could arise

in the game.

After World

War II, Go began the rise to prominence it holds today in Korea.

A professional institute was established and pro games began to be played.

Players emerged with great strength and understanding of the game.

When international tournaments began to be held Korea would often come

out on top. In the 90’s Korea became the undisputed top Go power

in the world. Many titles were consistently held by the top Korean

players and still are today. Also the person considered the strongest

player in the world is Korean, Lee Chang-Ho.

Finally we

look at Go in Japan. After it had spread to the country in the 8th century

the next period of real interest in Japanese Go history isn't until the

Tokugawa Shogunate period.

Before this

time, there would often be Go tutors who worked specifically for the emperor,

the best players in the country with the sole purpose of teaching the emperor

to play better. When the first Tokugawa Shogun came into power he established

an official government post for the best player in the country to be personal

tutor to the shogun, the Meijin Godokoro. A highly coveted position, the

Meijin Godokoro had power, prestige, and also a direct line to the shogun.

Go support

by the shogun didn't stop there. In 1612 the government began subsidizing

the four major Go houses at that time: the Honinbo, Inoue, Hayashi, and

Yasui. For the next 250 years these schools were supported by the government

until the Meiji Restoration brought their funding to an end.

Also at this

time the castle games were started. A castle game is a Go game between

two of the best players around, usually from the heads or upper ranks of

the four schools, played before the shogun at his castle. The first one

was held in 1605, but it wasn't until 1628 that it was made an official

ceremony and after 1667 they began to be held annually. The most famous

participant of these castle games is Honinbo Shusaku, who in nineteen consecutive

castle games never lost once. The castle games also suffered when the Meiji

Restoration came about, they were never held again after 1863.

With all the

turmoil in Japanese Go during the Meiji Restoration, game play around the

country suffered a great deal. This was one of the low periods of Go in

the country until newspapers began to help sponsor it. Newspapers would

publish weekly Go columns, discussing games and strategy and giving the

average person an easy look into the world of professional Go. As years

went on newspapers began to sponsor tournaments, and today all the major

tournaments in Japan are supported by newspapers.

Japanese Go

also benefited by the creation of the Nihon Kiin in 1924. The Nihon Kiin

is the main Go body in Japan; it organizes professional events and handles

rank promotions and such. The last head of the Honinbo school helped to

establish the Nihon Kiin by handing over the title of Honinbo to be determined

by tournament through the organization. Today all titles are determined

through tournaments in this way.

Go in Japan

today is suffering. Constantly behind other Go powers China and Korea in

international play, Japan is searching for a way to retake its place as

the top Go power in the world. Help is coming from a strange place these

days, anime and manga. Hikaru No Go is the story of a boy named Hikaru

and the ghost of a Heian period Go tutor to the emperor named Sai. The

two are forced together when Hikaru finds the ancient Go board the ghost

is trapped inside in his grandfather?x2019;s attic. Hikaru then begins

to learn to play and enjoy Go from Sai and quickly becomes a great player.

The popularity of the manga led it to being made into an anime that is

equally as popular. Due to this new phenomenon Go has had resurgence among

the young in Japan, with classes for children quickly filling up and new

classes starting all around. This will hopefully bring about many new great

players to help Japan reach the top of the Go world again.

|

The

Japanese board game of Go, known in China as Wei Qi and Korea as Baduk,

is an ancient game of strategy played thougought most of East Asia. As

it spread from China to Korea and Japan, the game developed and grew in

each. All developing their own styles and ways of playing, the game today

is quite international and those three countries regularly compete to see

who is the strongest.

The

Japanese board game of Go, known in China as Wei Qi and Korea as Baduk,

is an ancient game of strategy played thougought most of East Asia. As

it spread from China to Korea and Japan, the game developed and grew in

each. All developing their own styles and ways of playing, the game today

is quite international and those three countries regularly compete to see

who is the strongest.

China

is the obvious place to start, as the game first developed here and has

had the longest time to be a part of the culture. Some of the earlier

definite references to Go can be seen in the works of Confucius. He makes

mention of it in an unflattering manner, causing future generations to

at times regard Go as un-Confucian. Later it begins being known as

a game of skill and those who are good at it tend to be known as wise men.

China

is the obvious place to start, as the game first developed here and has

had the longest time to be a part of the culture. Some of the earlier

definite references to Go can be seen in the works of Confucius. He makes

mention of it in an unflattering manner, causing future generations to

at times regard Go as un-Confucian. Later it begins being known as

a game of skill and those who are good at it tend to be known as wise men.