|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

During the entire space race, the Soviet Union and the United States

were wrapped up in the Cold War. Relations between the United States

and the Soviet Union were very tense. This fact drove the space programs

even harder. The United States felt obligated to prove democracy

superior to communism in every aspect, and the Soviet Union sought to prove

the opposite. Science, embodied in the space race, was an arena that

both governments could use to prove not only the political superiority

of their state, but also the minds that it produced. The Cold War

and its tensions would prove to be a catalyst for many events within the

space race and vice versa.

The closing of WWII and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with the newly developed atomic bomb, ushered in the space race. After single bombs destroyed the entire cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world realized that warfare had taken a dramatic turn. The importance of rocketry grew immensely in the field of warfare. Although scientists had planned to use rockets in some sort of space exploration program, funding for rocketry was allocated solely to the development of rockets to be used in war immediately following World War II (Levine, 17).

The space race came at a time in history when great tensions enveloped the world. With the Cold War in full force, the space race became a reflection of the conflicts between the Soviet Union and the United States. The advances made during the space race were not made for the sake of science, but instead to assert the superiority of one government over another. Throughout the race both nations attempted to one-up the other which allowed tensions to mount in a very similar way to the Cold War.

After World War II, it became evident that there were primarily two nations interested in developing military technology. They were the United States of America and the Soviet Union. Both countries had captured V2 rockets and also some of the developers of the rockets from Germany after the war (Schefter, 11). With German scientists to help them, both the United States and the Soviet Union were interested in developing intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). These missiles would have the ability to hit any location on Earth, but in order to do so they had to exit the atmosphere (Levine, 6) . The design teams in both the Soviet Union and the United States focused on creating a rocket with enough power to exit the atmosphere carrying a missile along with it. Along with the German engineers, both nations created a strong rocket division, and within those divisions there were many scientists with the hope of using the rockets to place a spacecraft into orbit.

With the successful development of many ICBMs, both nations were able to study phenomena in higher altitudes. The United States and the Soviet Union created an international agreement which stated that the years 1957-1958 would be a time for scientists to study the Earth, its atmosphere, and the space around it (Diamond, 20). This time was to be called the International Geophysical Year (IGY). The United States, during the presidency of Eisenhower, announced its plan to place a scientific satellite in orbit around the Earth as part of the IGY (Diamond, 20). One of the main motivations for this early satellite was to establish nation sovereignty over America’s airspace. After hearing this official announcement, the Soviets saw a window of opportunity to get into space first and began planning a satellite of their own, except they made no official announcement at that time. On October 7, 1957, the Soviet Union placed the satellite Sputnik into orbit around the Earth (Sheldon, 47). The official announcement for this satellite was only given three days before the launch took place. The Soviet Union had placed a satellite into orbit around the Earth before the United States, therefore taking the first step in the space race. The only problem was that the United States had not yet realized that there was a race.

When the United States attempted to answer Sputnik with their own satellite, a failure occurred. The United States planned to enter a satellite called Vanguard into space on December 6, 1957 (Schefter, 45). Instead of lifting off of the launch pad and rocketing into orbit around the Earth, the satellite did not rise fast enough and fell over and burned. While the United States’ space program recovered from the failure and developed rockets similar to the Vanguard that were able to get into orbit, it was primarily the Vanguard failure that was remembered by the public.

In between the launches of Sputnik and Vanguard, the Soviets were able to launch Sputnik 2, which sent the first living being in space. A dog named Laika was entered into orbit on March 26, 1957 (Sheldon, 47). She survived seven days in space before her oxygen supply ran out. With Sputnik and Sputnik 2, the Soviet Union took command of the space race.

After the Vanguard disaster the Army took over where the Air Force had left off. The Army’s program, led by Werner von Braun, a German scientist, created a rocket satellite combination called Explorer 1 (Levine, 69). Explorer 1 was released on January 31, 1958 and successfully orbited the Earth (Levine, 69). This was the United States first real answer to the Soviet Union in the space race.

By mid 1958 the space race was going strong. Together the Soviets and the Americans had attempted to put satellites into space 14 times, with six successes. Sputnik 1, 2 and 3; Explorer 1 and 3; and one Vanguard satellite had been placed into orbit. The only differences between the success rate of the Americans versus the Soviets was that the Soviets only announced their successes and kept their failures secret, while the United States had a policy of announcing both. This method made the Soviet space program seem perfect while the American program looked flawed. The American public became ashamed of their space program and wondered why the Soviets could get things into space perfectly and they could not.

At this time the Army, Air Force, and Navy competed for control over the American space program. President Eisenhower was forced to decide who would run the program and how it should be run. Eisenhower did not want the space program to seem too militaristic, so stemming from a suggestion from Vice-President Nixon, he changed the civilian run agency National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) to National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) (Schefter, 47). There, Eisenhower could draw the best people from each military branch to develop a very strong space program. NASA’s initial goal was to put a man in space, and they were determined to do it before the Russians.

In order for the United States to put a man in space, they first needed a man who was willing to go. NASA developed a list of necessary criteria for an astronaut to have, and by late January 1959, a list of 324 eligible men had developed (Schefter, 51). Based upon mental and physical tests, a task team was told to select the six best men for the job. After discussing all of the candidates, the field was narrowed to seven and the panel could go no further. These seven men became know as the Original Seven and were: Gus Grissim, Deke Slayton, John Glenn, Gordo Cooper, Wally Schirra, Scott Carpenter, and James Lovell (Schefter, 51). On April 9, 1959, NASA announced to the world that these were the men that would explore space for the United States (Schefter, 53).

At about

this same time, the Soviet space program was developing another one of

their many firsts in the race for space. On January 2, 1959, Lunik

1 was launched (Diamond, 147). Instead of just orbiting the Earth,

the Russians had much more planned for this rocket. The initial idea

was to pack the tip of Lunik with an atom bomb, but after discarding that

idea they settled for a subtler alternative. They placed a pyrotechnic

container in the rocket which released a yellow sodium cloud into the atmosphere.

This cloud was visible from the British Isles to Japan (Schefter, 78).

But that was not where Lunik’s tricks ended. The Russians planned

to have Lunik continue on and hit the moon, but it missed by 3,728 miles

(Schefter, 78). The mission was not a failure, though, because Lunik

was able to surpass the distances of all previous satellites and truly

enter into space. The Soviet Union, it seemed, had once again stepped

the space race up a notch.

At about

this same time, the Soviet space program was developing another one of

their many firsts in the race for space. On January 2, 1959, Lunik

1 was launched (Diamond, 147). Instead of just orbiting the Earth,

the Russians had much more planned for this rocket. The initial idea

was to pack the tip of Lunik with an atom bomb, but after discarding that

idea they settled for a subtler alternative. They placed a pyrotechnic

container in the rocket which released a yellow sodium cloud into the atmosphere.

This cloud was visible from the British Isles to Japan (Schefter, 78).

But that was not where Lunik’s tricks ended. The Russians planned

to have Lunik continue on and hit the moon, but it missed by 3,728 miles

(Schefter, 78). The mission was not a failure, though, because Lunik

was able to surpass the distances of all previous satellites and truly

enter into space. The Soviet Union, it seemed, had once again stepped

the space race up a notch.

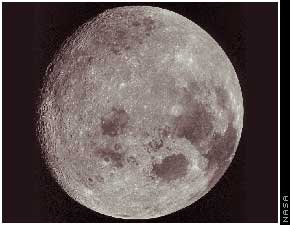

After Lunik 1, the Chief Designer, head of the Russian space program,

reacted to the U.S. announcement of astronauts with one of his own.

In October of 1959, the Chief Designer put out a press release that announced

that he had his own astronauts in training (Schefter, 108). This

was later proven to be false. The Russian Space program did not want

to seem behind in the Space Race even if that was in fact the case.

When looking at the space race in retrospect, it is amazing to see how

much of the Russian space program was a lie. Right before his false astronaut

announcement, the Chief Designer had placed something in space that was

very real. With the launch of Lunik 3, the Russians created the first

photographs of the far side of the moon (Sheldon, 48). With the two

breakthroughs, flying past the moon and obtaining pictures of the moon,

the space race had developed the clear goal of landing a man on the moon.

The first nation to do this would be the undisputed winner.

Before either nation could win the race, both had a huge obstacle

to surpass. Russia and the United States both wanted to get a man

into space and ultimately to the moon, but there was one problem.

Neither nation had developed a technology to get a man back to Earth safely.

Along with that major complication, doctors on both sides were trying to

determine the effects of long periods of weightlessness on the human body.

Both nations were far from their goal, but almost dead even in the race.

While NASA developed their manned space program, John F. Kennedy became president. Eisenhower, who was very conservative with the risks he was willing to take with the space program, was replaced by a younger man who was excited by the prospect of having a man in space. This factor helped to push the program along. The first blow from the Russians to Kennedy’s presidency was the man they put into space first. NASA had planned to put a man into space in early 1961, but due to pressure from the medical community the flight was delayed to allow for more test flights with apes. On April 12, 1961, because of NASA’s caution, the Soviet Union placed the first man in space (Harvey, 5). Yuri Gagarin entered space at 9:06 a.m. in his spacecraft called Vostok 1, orbited the Earth one time, and then returned (Harvey, 5). The soviet space program hailed the mission as successful, but later the world would find that Gagarin was forced to eject from the craft, therefore invalidating Vostok 1 as being technically successful (Harvey, 5). This instance once again followed the pattern of Soviet dishonesty and continued to lower morale for NASA.

Five days after Russia beat the United States into space, a band of rebels invaded communist controlled Cuba from Florida. As the invasion developed, the United States did not send the air support it promised. The invasion then failed miserably, and the entire Bay of Pigs ordeal was disastrous for the United States (Schefter, 137). Morale in the United States was very low; it seemed that there was nothing they could do to beat the Russians. Kennedy needed to do something to eclipse the Russians. At the same time, NASA was preparing for their first manned space flight. Due to weather delays, the flight was pushed from April 25th to May 5th (Diamond, 56). On that morning Allan Shepard got into his Mercury 7 capsule and was launched into space at 9:32 a.m. (Diamond, 56). While in space, he preformed a successful 15-minute suborbital flight. Although the United States had successfully put a man in space, the Soviets were still ahead of them with their full orbit of the Earth.

President Kennedy needed something that the United States could do before and better than the Russians. He wanted to pick something so hard that both the Americans and the Russians would have to start from scratch. After consulting with some of NASA’s top officials, he decided on the moon as his goal. When he spoke to Congress on May 25, 1961, he proposed his idea, “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”(Schefter, 143). Two weeks after his statement, Kennedy met with Nakita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union. At this meeting Kennedy suggested that the two nations combine space programs to create a lunar program (Schefter, 146). Khrushchev declined the offer and was later quoted as saying, “(a combined space program) will mean opening up our rocket program to them. We have only two hundred missiles, but they think we have many more.”(Schefter, 146). After being asked if he had something to hide, he stated, “It is just the opposite. We have nothing to hide. We have nothing. And we must hide it.” (Schefter, 146). Kennedy had just redefined the race, and Khrushchev had redefined the separation between the two participants.

In the next phase of the race only one type of spacecraft mattered, and that was manned. There were huge strides being taken in satellite development. The technological and industrial strength of the United States allowed it to dominate the satellite divisions of weather, communications, scientific, and spy (Schefter, 155). On the whole, America dominated space and was the first nation to truly see its benefits. But that part of the space race did not matter in the eyes of the public. The only race that mattered now was to the moon, and the time limit had been set. If the United States did not get a man to the moon by the end of the decade, they were disqualified from the race.

On July 21, 1961, the United States sent Gus Grissom into space for a flight similar to that of Shepard’s (Schefter, 146). The only problem with the flight was that Grissom’s ship was lost in the ocean after a controversial complication (Schefter, 146). Once again America’s faith in the space program was diminished. Another blow was struck to that faith when before NASA could get a man into orbit, the Russians put Vostok 2 into space for nearly seven hours (Harvey, 6). After this point in the space race both nations were forced to take things slower in order to develop more advanced spacecraft to achieve their goal.

On February

20, 1962, NASA was finally able to place a man into orbit around the world

(Diamond, 54). After switching to a more powerful rocket, John Glenn

was sent into space in the Mercury Friendship 7 capsule (Diamond, 54).

This flight renewed spirit in the American space program. The American

public once again backed NASA and genuinely believed that the United States

would win the space race.

On February

20, 1962, NASA was finally able to place a man into orbit around the world

(Diamond, 54). After switching to a more powerful rocket, John Glenn

was sent into space in the Mercury Friendship 7 capsule (Diamond, 54).

This flight renewed spirit in the American space program. The American

public once again backed NASA and genuinely believed that the United States

would win the space race.

After placing one more spaceship in orbit, the Russians had exhausted their inventory of spacecraft. While they had built spacecraft to take men into space, their spacecraft had nowhere near the pilot control capabilities of the American ships which would be necessary to achieve a moon landing. To build up the needed space fleet, it would take the Soviet space program at least a year, which forced the program to slow down dramatically. In 1961, the United States tried for space 41 times and succeeded on 29 (Diamond, 112). The Soviet Union succeeded on five launches out of only nine (Diamond, 112). The industrial strength of the United States was creating an edge over the Russians.

Although the United States may have gained an edge over the Russians, it was the Russians who took the next step in the race. On August 11, 1962, the Soviet Union launched Vostok 3 with Andrian Nikolayev aboard (Diamond, 117). The next day, following almost the same launch trajectory, Pavel Popovich was launched into space on Vostok 4 (Diamond, 117). While in space the two ships were able to get within 3.2 miles of each other, taking the first step in a space rendezvous and docking, which would be necessary for a moon mission (Diamond, 117). Although the Russians did not use any new technology to get this close, it appeared to the American public as though the Russians had once again taken the lead from the Americans.

The Russian flights put a new pressure on President Kennedy to once

again get involved with the program. In September of 1962, Kennedy

took a tour of NASA’s Houston command center (Schefter, 182). After

his tour he gave a speech at Rice University. With this speech he

was able to renew public spirit in the space program. He said, when

commenting on the space program:

We mean to be part of it, we mean to lead it, for the eyes of the world now look into space, to the moon and to the planets beyond, and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest but by a banner of freedom and peace (Schefter, 183).

At the end of his speech he put a perspective on the space race

that would help America understand the difficulty, “We choose to go to

the moon in this decade and to do the other things not because they are

easy, but because they are hard.” (Schefter, 183).

Just weeks after Kennedy had made his speech on peace, the Cuban Missile Crisis began. Nakita Khrushchev was forcing confrontation by putting intermediate-range attack missiles in Cuba (Schefter, 185). The Soviet Rocket Force was a growing power, and the country’s success in space had driven home the point that the Russian rockets were a strong threat. Khrushchev knew how to get what he wanted by exploiting his propaganda success (Schefter, 185). After Kennedy blockaded the sea-lanes around Cuba, turning back Soviet ships carrying additional missiles, the two countries came to an agreement. Khrushchev was forced to remove his missiles from Cuba publicly, while Kennedy was allowed to remove missiles from Turkey quietly (Schefter, 185). Peace, though awkward, had returned to the Cold War.

The open policy of the American space program allowed for the Chief Designer to upstage the Americans easily. Just as NASA was finishing up its Mercury program and getting ready for the Gemini program, Russia gained ground in the space race. On June 14, 1963, Vostok 5 was placed into orbit for a record-breaking five days (Oberg, 24). This amount of time more than eclipsed the 34 hours that America had been in space. A few days after Vostok 5 was launched, Vostok 6 entered space (Oberg, 24). The first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, piloted Vostok 6 (Oberg, 24). Not only did these two flights set records for total time in space and the first woman in space, but they were also able to get as close as 3.1 miles from each other (Oberg, 24). The Russians, it seemed, were running circles around the Americans in the space race. Before NASA could get two men into space at the same time, the Russians had done it twice and once with a woman in the pilot’s seat.

After the Cuban Missile Crises, communication between the United States and the Soviet Union was improved. In autumn of 1963, Kennedy once again proposed that Russia and the United States join forces to get to the moon (Schefter, 193). Khrushchev did not say no so quickly this time. Later, he made a statement after being asked why this situation was different from the last time, “Now we have five hundred missiles, not two hundred. We can destroy 500 American cities and that is enough to keep Kennedy from attacking us.” (Schefter, 193). But before Khrushchev could give an answer, Kennedy was assassinated. After Kennedy’s assassination, Khrushchev made the statement to reporters that the goal of the Russian space program was not to get to the moon (Schefter, 193). A year later Khrushchev was deposed by the Russian military (Schefter, 194). The Cold War continued to get worse. The Space Race also continued, but one of the runners was getting weaker.

In order to stay in the space race, the Russians wanted to upstage Gemini, the American two-man space program, before it even started. By dangerously modifying the one man Vostok capsule, the Chief Designer crammed three cosmonauts into Voskhod 1 on October 6, 1964 (Harvey, 7). Although Russia seemed to be making great strides in the space race, it was all just smoke and mirrors.

The American Gemini program had been designed from the start to facilitate space walks (Oberg, 41). Once the Chief Designer got wind of this, he began working on a space walking plan of his own to beat the Americans. He designed Voskhod 2 to have one purpose: have a Russian space walk before any Gemini flew with astronauts (Oberg, 42). Using a very risky and untested process, Russia achieved the first space walk in late March, 1965 (Oberg, 42). With this victory, the Russian space program was content with its progress; it canceled the rest of the Voskhod plans and moved on to work on other projects.

With Gemini IV, American began to catch up in the space race. Ed White preformed the first American space walk, and along with Jim McDivitt more that doubled American’s longest spaceflight (Diamond, 94). America’s imagination was once again engaged and the space race was back on the front pages. For the first time it looked as though the United States might have a chance to win.

After the Mercury program had put exploratory spacecraft into orbit successfully, NASA finally felt ready to have a first of its own. On March 16, 1966, the Gemini VIII spacecraft was launched into space with Neal Armstrong and Dave Scott aboard (Diamond, 99). A few days before they entered orbit, an Agena target vehicle was launched. While in space they preformed a perfect docking (Diamond, 100). These techniques were essential to the space program because one of the basic components to the lunar plan was the ability to dock with another ship.

After a few more Gemini flights the program was ended. In the 21 months of the program, 16 astronauts went into space (Schefter, 241). They had done rendezvous, docking, and fired Agena engines into higher orbits. They had also performed multiple space walks and worked out techniques to combat the fatigue and stress of working in a pressurized space suit while weightless. They had flown long and come home healthy. Every manned spaceflight record now belonged to the United States except for orbiting a woman and flying three men at a time. America may not have been the first to achieve most of the records, it had just been the best. In the same 21 months that Gemini took place, the Russian space program did nothing in public (Schefter, 241).

As both nations geared up for what seemed would be the last lap of the race, disaster struck. For America, Apollo 204 killed Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom, and Ed White (Diamond, 41). The deaths forced NASA to reevaluate priorities and create more checks to ensure the safety of crews. For Russia, the death of Vladimir Komarov was much more destructive. After the disaster, the Russian manned space program came to a complete stop (Harvey, 9). Both nations in the space race were in trouble; it was just that the Russians troubles were much worse.

America launched Apollo 7 in October 1968, which was a successful mission preparing for the later moon flights (Levine, 192). A few weeks after Apollo 7, Russia reentered the space race. Vaily Mishin and Georgy Beregovoy entered space in an attempt to rendezvous and dock (Schefter, 270). Beregovoy was only able to bring his craft within 650 feet before running out of fuel (Schefter, 270). Although the mission was unsuccessful, it raised fears that the Russian space program may be making a move on the moon. Before America could think anymore about the Russian space program, Apollo 8 was launched. On Christmas Eve, 1968, Apollo 8 entered lunar orbit (Schefter, 272). Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders stayed in lunar orbit for twenty hours and orbited the moon ten times (Schefter, 272). It was not a great year in American history: the Tet Offensive was a disaster for the Vietcong, Lyndon Johnson threw in the towel over Vietnam, and Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were murdered. However, Apollo 8 seemed to be a bright spot in all the darkness (Schefter, 273).

In Russia, the space program put Soyuz 4 into orbit on January 14, 1969 with Vladimir Shatalov aboard (Harvey, 10). The next day, Yevgeny Khrunov, Aleksei Yeliseyev, and Boris Volynov were launched into space in Soyuz 5 (Harvey, 10). These two craft were able to dock, where they preformed a two man space walk and a crew transfer. Because of this, Boris Volynow came home alone a day later alone (Harvey, 10). The Soyuz program made it obvious that the Russians were aiming for something other than the moon.

In America,

time was running out. The Kennedy deadline was fast approaching,

and after two satisfactory preparatory missions, Apollo 11, the moon mission,

was ready to go. On July 20, 1969, the command module Columbia

and the lunar module Eagle of Apollo 11 were separated on the back side

of the moon (Schefter, 276). The Eagle was given permission

to begin descent onto the lunar surface, and at 3:17 p.m. Houston time

the Eagle had landed (Schefter, 288). As Neil Armstrong exited the

Eagle and spoke his famous words, “That’s one small step for man.

One giant leap for mankind.”, America had won the space race (Schefter,

288).

In America,

time was running out. The Kennedy deadline was fast approaching,

and after two satisfactory preparatory missions, Apollo 11, the moon mission,

was ready to go. On July 20, 1969, the command module Columbia

and the lunar module Eagle of Apollo 11 were separated on the back side

of the moon (Schefter, 276). The Eagle was given permission

to begin descent onto the lunar surface, and at 3:17 p.m. Houston time

the Eagle had landed (Schefter, 288). As Neil Armstrong exited the

Eagle and spoke his famous words, “That’s one small step for man.

One giant leap for mankind.”, America had won the space race (Schefter,

288).

After winning the race, America lost interest in the moon. Apollo 17 was the last lunar mission in 1972 (Oberg, 42). America began work on the Skylab space station project. A Russian and American collaboration in space took place in July 1975 with the Apollo-Soyuz mission (Oberg, 45). As a temporary break in the Cold War tensions, President Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev wanted to prove that the United States and the Soviet Union could work together in space. The Cold War also ended. The end began with the signing of SALT I by Nixon and Brezhnev in 1972, and fully came to a halt in 1991 with the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (Oberg, 45). The tensions, seen during the Cold War that were reflected in the space race, were finally put to rest.

Diamond, Edwin. The Rise and Fall of the Space Age.

Garden City: Doubleday, 1964.

Harvey, Brian. Russia in Space: The Failed Frontier?

Chichester: Springer, 2001.

Levine, Allen J. The Missile and Space Race. Westport:

Praeger, 1994.

Oberg, James E. The New Race for Space. Harrisberg:

Stackpole Books, 1984.

Schefter, James. The Race. New York: Doubleday,

1999.

Sheldon, Charles S. II. Review of the Soviet Space Program.

New York: McGraw- Hill, 1968.

http://www.nasa.gov This site is the main NASA page, a great place to find anything you want about space.

http://quest.arc.nasa.gov This site is stemmed from the NASA website as an educational tool.

http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/sputnik This site has the history of the Sputnick satellite.

http://www.nasm.si.edu/galleries/gal114/SpaceRace/sec300/sec320.htm This site has a good (brief) history of the space race.

http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/ops/docs/coldwar_timeline.htm This site is a Cold War timeline.

http://www-istp.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/ This site has a good history of spaceflight and flight itself.

http://www-spof.gsfc.nasa.gov/stargaze/Stimelin.htm

This site has a timeline of flight.

Site Created by:

Allison Schwab