Aquinas in Context Fall 2017 KU Leuven HIW

Prof. Andrea Robiglio, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

Prof. Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI USA

Aquinas in Context Fall 2017 KU Leuven HIW

Prof. Andrea Robiglio, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

Prof. Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI USA

Thomas Aquinas Fall 2014:

Theomorphism or Anthropomorphism? Conceiving God in Aquinas and his Arabic Sources

Prof. Richard C. Taylor, Marquette University, Milwaukee

(email: richard.taylor@hiw.kuleuven.be or Richard.Taylor@Marquette.edu)

Prof. Andrea Robligio, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

(email: Andrea.Robiglio@hiw.kuleuven.be)

Last website update 29 November 2013

Live Classroom Course Meeting Times*:

28 August - 18 September: Thursday 9:00 - 11:00 am U.S. Central Time

25 September - 18 December 9:00-11:00 am US Central Time / 16h-18h European Central Time

Brief Course Description

In recent years the powerful influence of the Arabic tradition on the development of the philosophical reasoning and insightful doctrines of Aquinas has been firmly established in international conference meetings and publications on Aquinas and ‘the Arabs’. In connection with that work, this course will begin with five weeks of a graduate introduction to Aquinas and then become an international collaborative graduate seminar with the subtitle, “Theomorphism or Anthropomorphism? Conceiving God in Aquinas and his Arabic Sources.” Team taught by professors at Marquette and the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, this course will have assigned readings, video lectures, an online discussion board, student presentations (beginning in the sixth week), and weekly live video meetings for two hours of discussion involving students at Marquette and KULeuven as well as other selected international auditors. The content focus will be on issues, proofs, attributes, divine actions and more with particular reference to the initial (and often lasting) reasoning of Aquinas formed in connection with his use of ideas and arguments from the Arabic tradition. The course will close with four weeks of lectures on conceptions of God developed by later thinkers in engagement with the account of Aquinas. The structure of the course will follow the model found at https://academic.mu.edu/taylorr/Aquinas_Fall_2013_MU_KUL/Course_Description.html.

Marquette grading will be based on course participation (50%) and a final professionally prepared course paper of 20-25 pp. (50%).

Fall 2016 at Marquette Aquinas and ‘the Arabs’: Five Major Issues

Fall 2016 at KUL Aquinas in Context: Memory, Dreams and Prophecy

Fall 2015 Aquinas and Bonaventure on Divine Creation and Hhuman Knowledge

Fall 2014 Aquinas: The Nature & Attainment of Happiness

Fall 2013 Aquinas: Metaphysics

Fall 2012 Aquinas: Soul & Intellect

Fall2011 course, Aquinas and the Arabic Philosophical Tradition on ‘Creation’

Click HERE.

Aquinas in Context Fall 2017

Thursdays 16h-18h

Institute of Philosophy, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

Topic of the 2017-2018 Course:

“Aquinas and the Revolutions of Reason and Faith”

Faith and Reason have each been considered to be not only sources of justification for religious belief — as James Swindal right puts it — but also sources of reliable knowledge tout court. How a rational agent should treat claims derived from ‘faith’? How a believing and religious agent should treat concurrent claims derived from ‘reason’? Aquinas notoriously holds that there can be no conflict between the two—that reason properly employed and faith properly understood will never produce contradictory or competing claims, since they both derives from single origin and aim to the same purpose, viz., ‘truth’. In close conversation with Greek philosophy and the Abrahamic traditions, Aquinas worked out a sophisticated theory of theological reasoning in which both elements could find their place and role. If an immediate precursor to Aquinas like Bonaventure of Bagnoregio (1217 ca - 1274) has argued that no rational finite being could attain to truth “unless he philosophizes in the light of faith”, Thomas Aquinas maintains that the faith in eternal salvation shows that we have access to some “theological truths” that exceed, as such, the human reason. Aquinas also claimed, however, that a finite rational being could attain truths about religious claims by mere reason, i.e., without “faith”. In his Treatise concerning the Truth of Catholic Faith, the so-called Summa Contra Gentiles, Aquinas refers to a " twofold truth" about religious claims: “one to which the inquiry of reason can reach, the other which surpasses the whole ability of the human reason” (Bk I, Ch. 4). Now, in principle, no contradiction can stand between these two truths. However, something can be true for faith and inconclusive in philosophy as well as something could be philosophically (say, “scientifically”) true but irrelevant for faith. Any non-believer can attain to truth, though not to the highest truths which are attainable by faith only. But how to deal, in practice, when rational statements seem to challenge and contradict religious beliefs? How to navigate, furthermore, among conflicting reasons and different faiths? In case of conflict, in practice, between faith and raison, who may be stablish the truth? Aquinas is keenly aware of those dilemmas and also deals with more specific philosophical riddles. If The Truth is only one, why are two kinds of truth needed? In the Disputed Questions on Truth (e.g. q. 14, a. 9) Thomas contends that one cannot believe by faith and know by rational demonstration the very same truth since this would make one or the other kind of knowledge superfluous. He thinks there is complementarity and interplay of distinct truths, but none of them is just redundant. The position of Aquinas, in its historical context, does not win unanimous consent. A few of the theses condemned in 1277 reflect philosophical positions very close to Aquinas’s. Hence, to understand the highly articulated position of Aquinas we need to study his context and his intellectual sources. On the other hand, an accurate understanding of Aquinas’s thought must entail the familiarity with the previous genealogy of the debate, which has been at the roots of the Modern dialectical divide between Religion and Critical Thinking. A debate still relevant in the 21st century, as we can notice reading today’s newspapers.

The Fall Course 2017-2018 Aquinas in Context explores this crucial dimension of Aquinas’s thought and offer a careful reconstruction of the essential intellectual partners of this debate, starting from the exploration of key philosophical sources such as Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, al-Farabi, Avicenna, al-Ghazali, Averroes, Maimonides and the so-called Latin Averroists like the “Belgian” philosopher Siger of Brabant.

Cf. James Swindal, Faith and Reason, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, at:

http://www.iep.utm.edu/faith-re/#SH4e

and Paul Vallely, “Reason, Faith and Revolution by Terry Eagleton /The Case for God by Karen Armstrong”, The Indipendent, July 16, 2009, at:

A Remark on Method

In recent years the powerful influence of the Arabic tradition on the development of the philosophical reasoning and insightful teachings of Aquinas has been firmly established in international conference meetings and publications by members of the Aquinas and ‘the Arabs’ International Working Group and other scholars. It has also become abundantly clear that Aquinas is most fully understood through the method of source based contextualism involving the location of the thought of Aquinas in relation to the sources he himself studied in forming his own philosophical and theological doctrines. This is one of the key approaches that will be followed in these courses.

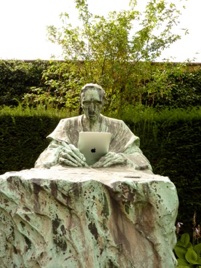

Désiré-Joseph Cardinal Mercier (1851-1926)

in the garden of the KUL Institute of Philosophy

al-Farabi Avicenna Averroes Aquinas Bonaventure Augustine